The Internet — A Threat or a Supplement to the Traditional Library?

Zenona Krupa

Abstract

This paper is based on empirical research on a group of 143 second–year and fourth–year students of Rzeszów University selected from three subject areas: Polish philology, history and mathematics, as well as 30 research workers — 10 persons from each above–mentioned field of study. The research used a poll questionnaire, and it was a pilot study for a bigger research project. The aim of the opinion poll is to show whether the Internet really will be a threat to traditional libraries, whether students and research workers will choose the traditional book or its electronic version and why, or whether the Internet will be only a supplement to the traditional library.

1. Introduction

The Internet has imperceptibly entered our life. It used to be the mass medium for initiates or researchers only. Now, it is present in almost every field of human activity [1].

- “At the turn of the twentieth and twenty–first century, it is difficult to meet a man, in civilised countries, remembering the world without the telephone or the radio. In a few dozen years the last witnesses of the origin of television will pass away. And the first generation of people who cannot imagine life without the Internet has already grown up. It has been able to create a virtual world, charming by its attractiveness. It has changed the way of living and reasoning of millions of people on every continent. Every day seems to confirm the explicit assumption made by the media and their forecast: what you cannot find on the Internet does not exist at all.” [2]

Still, uncritical enthusiasm for the new medium at its very beginning seems to have flagged a little. Critical remarks are directed at the Internet, and there are more and more sceptics, even among experts. In 1995, Umberto Eco noted:

- “Once upon a time, if I needed a bibliography on Norway and semiotics, I went to a library and probably found four items. I took notes and found other bibliographical references. Now with the Internet I can have 10,000 items. At this point I become paralysed. I simply have to choose another topic.” [3]

Ryszard Tadeusiewicz — a biocyberneticist and a computer scientist — expressed his negative opinion on the use of the Internet in science. His ability was precisely defining and presenting well–known opinions as the main disadvantages of the network. In his opinion:

- “the information is chaotically scattered and mixed up. And this makes it impossible to separate valuable sources from rubbish and fib. Informational smog dazzles, chokes, makes it difficult to get a good grasp and denies the chance of arriving safely at the quiet port of genuine learning.” [4]

The primary task of every library has always been to provide the reader with a source of information. Until recently it was mostly in the form of a book or a magazine. Nowadays, the most important things for library users are: quick service, full collection, quick information on the required material as well as getting access to world information resources. The Internet now offers the capability to find everything man has created and put on the network, and to get unlimited access to a huge amount of information resources. [5]

Will the younger generation of Poles, so fascinated with the Internet and called “the first screen generation” [6] by T. Goban–Klas, regard the image as an equal or even better resource, because it is simpler and more attractive than the book? Will they turn away from the service provided by the traditional library and sit down in front of the computer monitor to seek necessary information on the given subject? Still, perhaps there will be some conservative readers among them who will never give up that specific atmosphere of the library and will come there to read the traditional book with its shabby edges, yellowed pages and own history. Or will the Internet be, in the course of time, a supplement to the traditional library? I will try to answer the questions based on the results of my research.

2. Research Results

The material for the research was collected during summer semester 2005/2006 at Rzeszów University. Three subject areas were chosen for the research: Polish philology, history and mathematics. Research groups were then selected — 50 persons from each Department (Sociological and Historical, Mathematical and Natural Sciences, and Philological). All in all, the research comprised 150 students in the second and fourth years as well as 30 research workers — 10 people selected at random from each above–mentioned department. Some of the distributed questionnaires were not returned, and some of them were filled out incorrectly. Altogether, 143 questionnaires were analysed. Women consituted 65.7 percent of the total examined, while men were 34.3 percent. The research on the randomly selected group was based on a poll questionnaire, which included eight restricted multiple choice questions, where it was possible to give several answers as well as additional answers, as well as five non–restrictive questions, where the subject could express his or her own opinions. The aim of the opinion poll was to show whether the Internet really will be a threat to traditional libraries; whether students and research workers will choose the traditional book or its electronic version and why; or whether the Internet will be, in the course of time, a supplement to the traditional library.

Until recently, the library has been associated with bookshelves and catalogues where the user had to search out the necessary publication, then fill in the call slip and wait for the book, which often had already been borrowed by another reader. Now the Internet is available, online 24 hours a day, while the library has set working days and hours. Thanks to the Internet, one can scroll the catalogues when sitting home, in front of a computer screen, order any books in stock and collect them at any time. The Internet is at our disposal, providing unlimited access to a huge amount of information. We can even read electronic books (e–books), which are digital equivalents of the traditional ones, or the virtual press (e–newspapers) via the network. With such a facility, it would appear that nobody will use the library, but will acquire the necessary knowledge through the Internet only.

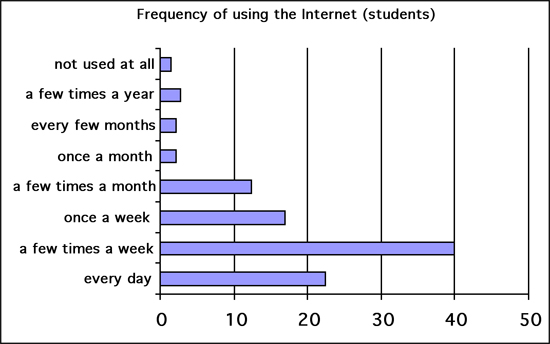

The Internet is becoming more and more popular, as more people use it while spending more time. The survey reveals that 22.4 percent of the students use the Internet every day, while 39.9 percent a few times a week. The subject area with the smallest number of users is Polish philology students with only 10.6 percent daily.

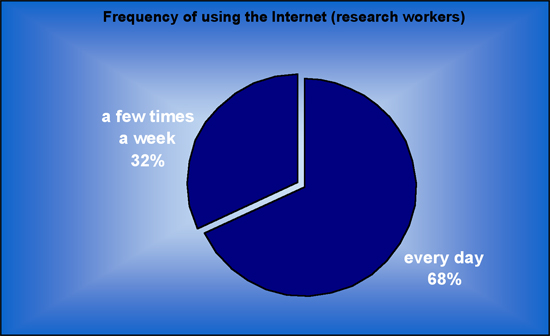

The research workers used the Internet more often: 68 percent every day, while 32 percent used it only a few times a week.

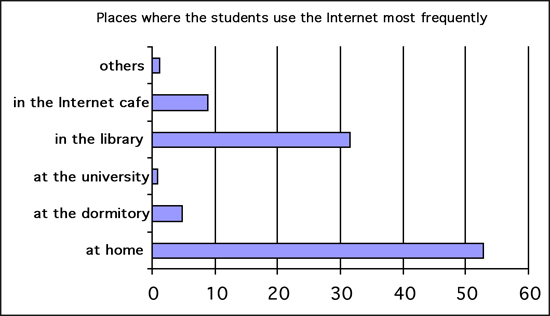

Figure 3: Places where the students use the Internet most frequently (percentage).

“I think that traditional reading is nicer and can teach respect for books which are disregarded today (mainly because of using the Internet).” — a fourth–year woman student of Polish philology;

“Reading books on the screen does not give as full reception as in the traditional form.” — a fourth–year woman student of Polish philology;

“I cannot concentrate on the text when I am reading it in the electronic version. It is easier for me to concentrate while reading the traditional version” — a fourth–year woman student of Polish philology);

“It is nicer to read the traditional book. You can put it aside any moment and return to it very quickly, as it is easier to transport.” — a second–year woman student of history;

“You can read books in any place, even if you do not have access to the Internet.” — a second–year woman student of mathematics;

“I prefer reading the traditional book, because it is more comfortable for me. I just cannot imagine reading the whole book on the computer screen. It would be awfully tiresome for me and give no pleasure.” — a fourth–year woman student of mathematics.

“The computer monitor has an adverse influence on my sight, so I prefer books in the traditional version.” — a second–year woman student of Polish philology;

“Eyes get tired very quickly when you read on the computer screen. And you sit in one position.” — a fourth–year woman student of Polish philology;

“Sitting at the computer is not comfortable, eyes get tired quickly and you have a headache.” — a fourth–year woman student of Polish philology.

“I can take a normal book and read it everywhere.” — a second–year woman student of Polish philology;

“The contact with books is very important for a real reader. Even the scent and kind of paper matters.” — a fourth–year woman student of Polish philology;

“I like a direct contact with books.” — a fourth–year woman student of history.

“It is much clearer when I read a newspaper on the computer screen.” — a second–year woman student of Polish philology;

“I read quite a lot of newspapers and magazines in the electronic version. I just want to save money and paper.” — a second–year woman student of Polish philology;

“I read the electronic version, because I have quick and free access to articles.” — a fourth–year student of mathematics;

“You need not browse through the pages.” — a fourth–year student of history.

“I like reading newspapers, but only in the traditional version, and not in a hurry.” — a fourth–year woman student of Polish philology;

“I am a traditionalist. I just like having a product in my hand, to have a look at the cover, browse through the pages.” — a second–year student of Polish philology;

“Although I use Internet magazines, I prefer the traditional version.” — a fourth–year woman student of Polish philology.

“I am in favour of keeping the traditional service as much as possible. I prefer the contact with a competent person to a technical device.” — a woman lecturer, history;

“As a matter of habit, it is easier for me to analyse the given text when it is presented in the traditional version.” — an assistant, mathematics;

“A matter of habit, a chance of being with the given book, the layout, etc.” — a woman, lecturer, Polish philology;

“The paper book can be read without additional operations, in convenient time and position — it is simpler after all.” — an assistant, mathematics;

“As a matter of habit and convenience, you do not ruin your sight.” — a lecturer, history.

“It is easier to read short texts on the monitor, and it is quicker to search them out in the electronic version.” — a lecturer, history;

“I usually read selected articles in newspapers, so the electronic version is better and cheaper.” — a lecturer, mathematics;

“It is simpler to store or alternatively delete them in the electronic version.” — a lecturer, mathematics.

“The Internet is a good supplement. For instance, when you have little knowledge of your subject, you can find some clues, but it will never replace the traditional library.” — a second–year woman student of Polish philology;

“It can be a supplement of the traditional library, considering the professionalism and richness of knowledge and information (as for the Internet, there are ups and downs).” — a second–year student of history;

“The Internet should be regarded as a supplement to the traditional library. I think that the present–day library cannot do without the Internet, which is, in many aspects, convenience for the readers.” — a second–year woman student of history;

“In my opinion, it can be a supplement to the traditional library, for intelligent people know that summaries alone, ‘cribbed’ from the Internet, will not be sufficient, but professional literature is needed.” — a second–year student of history;

“It can be a supplement, as not everybody has enough time to leave home, so they use the Internet, but I think that the traditional library will always have its supporters — book lovers.” — a second–year student of Polish philology;

“Definitely as a supplement to the traditional library and improvement in your work.” — a fourth–year woman student of Polish philology;

“Undoubtedly as a supplement to the traditional library, because we can easily find the book we are interested in. It is far more convenient than traditional searching out in the card catalogue and filling in call slips.” — a fourth–year woman student of history.

- “The Internet makes access to the book collection easier, supporting the work of the library this way.” — a lecturer, history;

“Only as a supplement to the traditional library. The Internet is only a quick way of searching out general information.” — a woman assistant, Polish philology;

“Definitely a supplement — a requirement of time, but for me, it cannot replace the library in everything. Still, I would emphasise the conveniences it gives in searching out information. You can use it at any time and any place.” — a woman lecturer, history;

“I think it is a supplement. In other countries people still visit the standard library and I do not think it will change quickly (also in our country). I do not think it will ever happen.” — an assistant, mathematics.

At home, 52.8 percent of the students used the Internet, and 31.5 percent, who wished to surf the net at home came to the library, where they used it free of charge and almost without limitations.

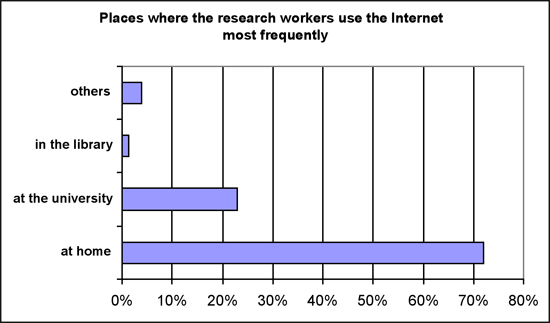

The research workers also used the Internet at home most frequently — as many as 72 percent of them, while 23 percent of the respondents used it at work at the university, and only 1.2 percent used the library. The students came to the library a few times a week at most, which makes 46.8 percent of the investigated, and 20.3 percent visited the library a few times a month. There were also respondents who do not use the library services at all, which constitutes 3.5 percent.

Another question asked about the reason why the respondents visited Rzeszów University Library. The respondents were to choose up to three most important answers, in their opinion, from several given ones. As many as 84 percent of the students claimed to come to the library to borrow the books they needed, 70 percent to study the literature in the reading rooms, and as many as 46.8 percent to use the Internet or e–mail. Eighty percent of the research workers came to the library to borrow the needed literature, 34 percent to study the literature in the reading rooms, and 24 percent to obtain bibliographic information on a specific subject.

The respondents were also asked to indicate the advantages and disadvantages of using the library and the Internet. The advantages of using the library, which they named most often, were: very good access to a large number of reliable and authoritative sources, free access to books, spending their time fruitfully between lectures and classes, comfortable reading rooms, the possibility of ordering books by computer as well as nice and efficient service. The biggest disadvantage of using the library was, according to them, too few needed books which they could borrow, long queues in the lending library and a shortage of some publications.

The respondents saw the advantages of using the Internet too, and above all others they named: quick access to necessary information, access to huge amounts of information, free access to newspapers and magazines (no charge or time limits in using these at the library), a chance of talking to friends (gadu–gadu instant messenger, chat, e–mail). The respondents also saw many more disadvantages. The biggest were: uncertainty about accuracy and truthfulness of the information found, “poor quality of the material,” “time eater,” and difficulty in getting access, which, as it seems, will cease to exist in the course of time, as more and more people have a computer and access to the Internet. And yet, as it turned out, some students suggested the need to pay for connections and the lack of their personal computer as disadvantages. That is why they use free access to the Internet in the library so often. On the other hand, the disadvantage of using the Internet is still, according to them, the small number of computer terminals in the library. (At present, the library has 51 computer terminals, of which 25 have access to the Internet for students and 11 for research workers). So we can see a very serious problem in using the Internet. The financial aspect is very important here; not everybody, as the survey shows, can pay for access to the Internet (especially for those who live in small towns and villages).

Another question had to do with reading e–books. These are, briefly speaking, computer files comprising the content of the given book. The most popular format of electronic publications, because of its universal applicability and ability, is the PDF format. In this format, electronic books can be read on the computer, regardless of its operating system, as well as on portable devices called palmtops [7].

Technological progress, which we can observe, makes the breakthrough applications, including e–books, more and more popular than reading print books. The survey reveals that 18.2 percent of the students read books in the electronic version. Most respondents (81.8 percent) prefer traditional books (which makes 3.4 percent of the total number of books read by those who prefer e–books). As for research workers, the survey shows that they read e–books much more often; 32 percent of them said yes, while 68 percent said no (this is 4 percent of the total number of books read by those who prefer e–books). 38.7 percent of the students said yes to the question: Do you read newspapers and magazines in the electronic version? Over 60 percent (61.3 percent) preferred the traditional paper format (which makes 9.3 percent of the total number of newspapers and magazines read by those who prefer e–newspapers). Over 80 percent (84 percent) of the research workers chose the electronic version of newspapers and magazines much more often, whereas 16 percent do not read them in this form (25.5 percent of all newspapers and magazines read by those who prefer e–newspapers).

Although the students read books, newspapers and magazines in the electronic version, 81.1 percent of them would definitely choose print books, while 18.9 percent would prefer to read them on the computer screen if they had the opportunity to use the book collection of Rzeszów University Library in the electronic version (both books and magazines). How did they state their preferences? Here are a few examples:

Health considerations are very important for many who choose between the electronic book and its traditional version. The investigated students give the following reasons for their choice:

The students also emphasized the lack of physical contact as one of disadvantages of Internet books:

As concerns reading electronic newspapers and magazines, students have a bit different approach. In this case, as many as 26.4 percent of the respondents express a desire for reading them in this form, while 73.6 percent still prefer the traditional paper version. Here are some comments illustrating the choice:

You can also find supporters of reading the print version of newspapers and magazines:

The research workers, having a choice between the traditional version and the electronic one, strongly opted for the traditional version as well, which was chosen by 80 percent of the respondents, whereas 20 percent preferred the electronic version. Let us see how they answered:

Twenty–eight percent of the investigated workers would prefer to read newspapers and magazines in the electronic form, while 72 percent still opt for the paper version. Here are some comments concerning the choice of the electronic version:

The respondents were also to answer the question: Where do you look for information concerning the subject of your research if you need it? The students had three versions to choose from. And so 12.8 percent of the examined students go straight to the library and look for the necessary information. Over five percent (5.7 percent) use the Internet only, in writing their thesis, and 81.5 percent use both the library and the Internet. As for the researchers, when they look for information, 31 percent of them go to the library, only four percent look for it in the Internet, and 65 percent use both the library and the Internet.

The last non–restrictive question was: What is the Internet — a threat or a supplement to the traditional library? A vast majority — 92.3 percent — of the investigated students definitely regard the Internet as a supplement to the traditional library, giving the following reasons for their preferences:

Only two of the students, 1.4 percent of the respondents, think that the Internet is a threat to the traditional library. For 96.7 percent of the research workers the Internet is a supplement to the traditional library, whereas 3.3 percent claim that it can be a threat:

3. Summary

Will the Internet be a threat to the traditional library or will it only be a supplement to its service? Does the rapid development of electronic media mean the end of the traditional printed book? As early as in 1962, Marshall McLuhan, in his famous book The Gutenberg Galaxy, predicted an early end to the Gutenberg era, replaced by a new “galaxy of electronic media.” According to him, the traditional book, printed on paper, was supposed to disappear definitely before the end of the twentieth century, which — as we know — did not happen [8]. It is possible that predictions about the future of the traditional library, which was supposed to lose in competition with the Internet, will not come true either.

According to the survey, the students usually use the Internet a few times a week. Almost 40 percent (39.9 percent) of the respondents answered this way, whereas the research workers use it much more often — 68 percent use it every day.

The investigated students usually come to the library a few times a week — 46.8 percent, while the researchers visit the place once a month — 60 percent. Students come to the institution to borrow the books they need, read the literature on the spot in the reading rooms as well as use the Internet and e–mail. As many as 84 percent of the respondents gave this answer. Eighty percent of the research workers (just like students) come to the library in order to borrow the needed literature, use the reading rooms and obtain the necessary bibliographic information.

The investigated students and researchers noticed, despite some disadvantages, big advantages of using the library and they named the following: very good access to a great number of reliable and authoritative sources, free access to books and professional service. The examined also saw the advantages of using the Internet. Still, there are much more disadvantages, e.g., uncertainity about the reliability of information, too much information on the given subject, low quality of information (mistakes and inexactness), time–consuming selection of information and finally, possibility of addiction.

The respondents read books, newspapers and magazines in the electronic version (the research workers seem to use it more often). And yet, being able to choose from the whole collection in the electronic version, both students and research workers would choose the traditional version. The survey reveals that the contact with the traditional book is fundamental for many readers. For some of them even the scent or kind of paper is very important. The investigated also emphasised the lack of physical contact as one of the dark sides of the Internet book, or the necessity of reading in one place. For those who choose the traditional version of the book, health reasons were very important. They think that sitting in front of the monitor for long hours is tiring for their sight and leads to headaches. There were respondents who preferred electronic versions, but mainly articles or short texts from newspapers and magazines. According to some respondents, it is easier to search and read digital versions. These electronic versions are also, in their opinion, easier to store or delete. For some, it also means a saving of time and paper.

As the survey reveals, the respondents, when looking for the information on the given subject, mostly look for it using both the library and the Internet. 81.5% of the students and 65% of the examined researchers answered this way. Definitely fewer people look for the needed information on the Internet only.

For most respondents (90% percent), the Internet is not a threat to the traditional library, it is only a supplement to its service.

Printed books and electronic ones will coexist with each other for a long time, and there will always be readers who will choose the specific atmosphere of the library and contact with the traditional book.