Transformation of the Library Profession within the Last Decade and its Future

Grażyna Wojsznis

Abstract

The origin of the profession of the librarian, i.e., its evolution from an occupation into a job between 1918 and 1939, the raising of the overall professional awareness of what it means to be a librarian after World War II and ongoing present–day debates upon the character of library activities mark the various stages of the shaping of this profession in Poland. Educating library staff, organizing library structures, working methods and communication styles within libraries have been evolving together with the economic, cultural and technological transformations taking place in this country. All these factors force the librarian to adjust and adapt to the changing needs of the library users, which is best observed in technical universities’ libraries.

The libraries’ vital activities have not always been centred around collecting volumes, cataloguing and making them available to the public. Originally library activities consisted mainly of collecting books, whereas a librarian (that is a courtier, lover and connoisseur of books, a custodian of the collection, often priceless) was supposed to protect the precious volumes from the readers. An independent profession of a librarian began to exist as late as the middle of the nineteenth century.

Polish librarianship began to develop intensively after 1917. Such phenomena as the campaign against illiteracy by making books and libraries more easily available to the general public and the guidelines pertianing to the national cultural policy created a new image of the librarian as a person who was knowlegeable about and actively engaged in social, political and economic life of those times. The post–World War I period also witnessed the development of the network of public, scientific/academic and specialist/professional libraries which stimulated the need to catalogue collections and create bibliographies in order to popularize collections outside specific libraries. All these activities called for professional library staff. [1]

After World War II further development of the profession was hindered by the lack of qualified academic staff in Poland. A librarian was no longer an academic and his/her research work stopped being top priority. This trend was reversed when library science developed as an independent field of study. Its main objective was to educate future librarians. Recent years have been marked by attempts to find new structures and working methods as well as the development of library staff and their professional skills.

The phenomena mentioned above have been reflected in the history of the Main Library of Szczecin University of Technology whose origins go back to 1946. The library was organized by people who had no professional background. Nor did they have any extensive experience as library workers. They raised their qualifications by attending various courses or taking up studies as they worked for the institution [2]. It is also difficult to allocate them to concrete work stations/positions within the library.

The year 1955, when Józef Czerni’s concept/idea of decentralizing by organizing specialized faculty reading rooms, marks the beginning of the library’s rapid growth. Originally the reading rooms were supposed to be branches of the Department for Lending the Holdings. However, it soon turned out that the necessity to coordinate, standardize the collections’ registers, make the structures transparent and take communal decisions or actions created a network of reciprocal relationships between faculty reading rooms and various other divisions of the Main Library. In order to function well, the reading rooms had to take over some of the library functions which theoretically were not theirs.

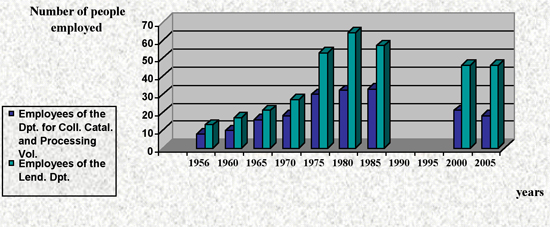

In spite of numerous problems, making the library collections available to the public has always been the library’s vital role which was occasionally performed at the expense of the other functions, i.e., collecting and cataloguing volumes. After all our main aim is and has always been to meet the readers’ needs. Figure 1 illustrates the proportion between workers employed in the two major library divisions.

-

Figure 1: Proportion between the number of workers employed in the library section responsible for collecting and cataloguing holdings and administrative duties and the number of workers employed in the department for lending and using the holdings and scientific information in the the Main Library of Szczecin University of Technology in 1949–2005. Source: Author’s own research.

Table 1 | |||||

| Year | Total number of employees | Number of employees in the Department for Collecting Cataloguing and Processing and in Administration | Number of employees in the Department for Lending the Holdings and Scientific Information | ||

| number | percentage | number | percentage | ||

| 1956 | 21 | 8 | 38 | 13 | 62 |

| 1960 | 27 | 10 | 37 | 17 | 63 |

| 1965 | 37 | 16 | 43 | 21 | 57 |

| 1970 | 45 | 18 | 40 | 27 | 60 |

| 1975 | 83 | 30 | 36 | 53 | 64 |

| 1980 | 96 | 32 | 33 | 64 | 67 |

| 1985 | 90 | 33 | 37 | 57 | 63 |

| 1990 | 78 | x | x | x | x |

| 1995 | 55 | x | x | x | x |

| 2000 | 67 | 21 | 33 | 46 | 67 |

| 2005 | 64 | 18 | 28 | 46 | 72 |

Table 1 shows the number and percentage of the employees working in the library section responsible for collecting, cataloguing and processing volumes and administrative duties and the number of workers employed in the department for lending and using the holdings and scientific information against the total number of workers employed in the Main Library of Szczecin University of Technology between 1956 and 2005.

Until 1985 the proportion was rather steady. The employment index for the library section responsible for collecting and cataloguing volumes was approximately 37.7 percent and the index for the department for lending and using the holdings and scientific information 62.3 percent. The subsequent years, i.e., the end of the 1980s and the 1990s, are the period of turbulent economic transformations in Poland which resulted in the downsizing of the library staff. Also the foundation of the University of Szczecin in 1985 meant transfer of books and employees of the Department of Economics Engineering and Transport to the newly created institution. Thus the statistics relating to that period is rather distorted by the lack of data.

After this period the total number of employees responsible for collecting and cataloguing volumes decreased to approximately 30 percent of the overall number of employees in favour of the number of workers employed in the department for letting out the volumes, which rose to approximately 70 percent.

The changes in the employment proportions between the two groups of staff in recent years reflect the transformations taking place in the library itself as well as its surroundings. They have been the result of economic, technological and social transformations in Poland and in the world and have brought about changes in the organization of work restructuring the library activities so as to focus more on the library user (Materska, 2002).

The pursuit of solutions which better meet the libraries’ needs means constant improvements of the libraries’ organizational schemas. Whether the schemas work or not is checked by how well the library meets its statutory requirements. [3]

The organizational schema predominating within libraries is the functional schema, i.e., typical division of the library activities into collecting, cataloguing, processing, storing, lending the holdings/volumes, scientific information and administrative–technical support sections. This schema best reflects the character of the processes taking place within libraries and creates an opportunity for high specialization. However, it still has its drawbacks. In the functional schema the division responsible for lending the volumes, which in fact is the last link in a long chain of processes taking place within libraries, is equivalent to the division responsible for collecting and storing the volumes, that is, it does not determine the course, quality and manner in which all the processes mentioned earlier are accomplished. Consequently, by making standards of services to users feature less prominently among the hierarchy of all library tasks, and thus making them less efficient, there is an imminent danger in creating “libraries for librarians”. [4] The process of lending holdings is located at the meeting point between what is structured and ordered and what is chaotic. Being dependent on the two it must be flexible, changeable and easily adaptable. [5] Problems requiring novel comprehenive approaches to the activities of any institution surface in the work of any organization, also in a library. Partial solutions will no longer do. [6]

The launching of a new computer library system at the beginning of the 90s was a big challenge for all library staff. It also influenced the library’s organizational structure and methods of work.

The multitude of tasks to be performed and the inability to increase the number of staff brought about the necessity of increasing assignments for staff, that is an introduction of a matrix structure. It consisted of creating special project groups outside the functional schema or on assigning employees to several different work stations. [7] So, for example, the interlibrary lending station was aided by an employee normally working for the Collecting Department, who worked part–time for each of the two divisions. Similarly, the Main Reading Room employee worked also for the Faculty Library. Such double assignements were permanent as opposed to temporary project groups which were occasionally formed when the situation required it, e.g., the beginning of an academic year, various exhibitions, the Library Week or some other tasks.

Merging of two positions is yet another phenomenon of a present–day library life. For example, employees of the Department for Collecting and Cataloguing actively participate in library training for first–year students or take Saturday duties in the Main Reading Rooms. Or the employees of the lending section work for the cataloguing sections in Faculty Libraries doing such jobs as creating topographical catalogues, assigning whole collections to individual thematic groups, making inventories of the holdings and their retrospection and the currently going on, retro–converting collections into the library computer system called ALEPH.

Seeking optimal solutions for the organization of library activities is an on–going process. The chances of success are best when the staff are higly skilled, which enables them to perfom duties at different posts. It is especially true for the Lending and Scientific Information Departments.

Computerization and, more generally speaking, the phenomena taking place in the field of science and technology, i.e., new information and communication technologies, economic and political changes require more extensive knowledge, higher education and continuous work on improving librarians’ qualifications.

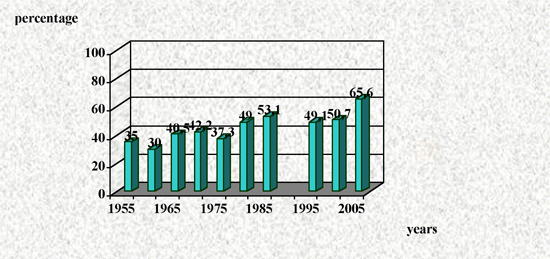

All this has been reflected in the proportion of staff with tertiary education in the overall number of staff in the the Main Library of Szczecin University of Technology.

-

Figure 2: Percentage of staff with tertiary education in the overall number of employees in the the Main Library of Szczecin University of Technology, 1955–2005.

Source: Author’s own research.

It follows from Figure 2 that the number of employees with tertiary education is growing steadily. Originally in 1949–1960 it was 30 percent of the whole number of workers; in the 1960s and 1970s it was approximately 40 percent, in the 1980s and 1990s it reached as high as 50 percent. Unfortunately, it is impossible to recover the data from 1980–1990. Recent years have been marked by further growth — in 2005 the index of tertiary education employees rose to more than 65 percent. The same data are illustrated in Figure 3 and Table 2.

-

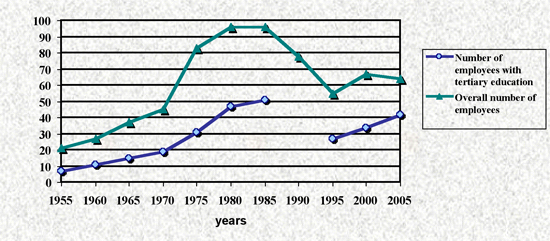

Figure 3: Number of staff with tertiary education in the overall number of employees in the Main Library of Szczecin University of Technology, 1955–2005.

Source: Author’s own research.

Table 2

Year 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 Number of employees with tertiary education 7 11 15 19 31 47 51 x 27 34 42 Overall number of employees 21 27 37 45 83 96 96 78 55 67 64

This phenomenon of steady growth is indirectly connected with the character of the institution in which the library exists. An academic library of a tertiary technical school must meet high expectations of its very specific users. These expectations force the staff to improve their skills, work methods, organization of work and keep up–to–date with the changing world of science and technology. New work stations such as electronic information, computer information, services to readers and trainings information desk, electronic documents, electronic journals, electronic publishing, internet information or, the most traditionally sounding, information searching desk are being created. These trends have been commented on in the article by Artur Jazdon entitled: “O nowych stanowiskach, specjalnościach i zawodach, czyli czy bibliotekarz to...nadal bibliotekarz?” (“On New Posts, Specializations and Professions or is a Librarian still...a Librarian”). [8]

When we deal with smaller teams of workers the phenomenon of creating of new posts is not so widespread. Rather we witness the phenomenon of extending the scope and range of tasks to be performed by an employee. It is becoming more and more difficult to specify the exact range of tasks for any specific employee as many a time they have to perform various duties characteristic for very different posts. Shifting the staff to do those jobs that are directly connected with performing services to the readers has been caused by reductions, closing of certain library divisions (reprographic room) or outsourcing (using private companies to do the jobs that have been so far done in the library, e.g., book binding). Such activities allow a given library a way to keep the number of employees at a steady, low level.

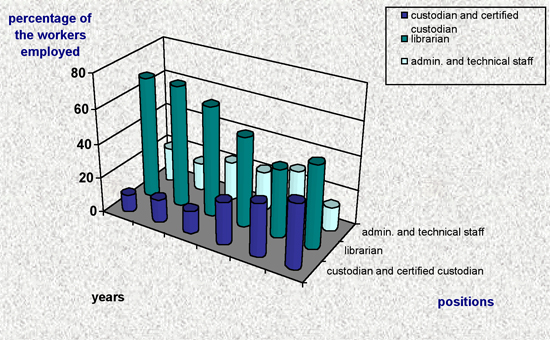

With regard to library staff basic activities we can divide the employees into library services and certified librarians. The library services constitute the biggest group which comprises the following positions: senior custodians, custodians, senior librarians, librarians, junior librarians, library assistants, senior storemen, storemen, senior and junior library technicians. Specific positions require different qualifications and skills and different level of education from secondary to higher education including an MA in Library Science for custodians and senior custodians. [9]

Figure 4 and Table 3 illustrate the percentage index for specific groups within the library service in the overall number of staff employed in the Main Library of Szczecin University of Technology since 1955

-

Figure 4: Development of the Main Library of Szczecin University of Technology library staff.

Source: Author’s own research.

The proportion of highly qualified staff with extensive experience as librarians (senior certified custodians, senior custodians, certified custodians and custodians) has been growing steadily. At the very beginning, in 1955, it was mere 10 percent and it remained at the steady level of 13 percent until the end of the 1970s. After 1985, when the Faculty Library of the Department of Economics Engineering and Transport was separated, the number of custodians constituted 25 percent of the total number of library’s workers. Since then it has been growing steadily to reach its highest level of over 37 percent in 2005. This growth is the result of employing new staff who hold university degrees in library science, extensive work experience and the elevation of qualifications for the staff already employed.

Table 3: Percentage index for specific groups of staff in the Main Library of Szczecin University of Technology.

Year 1955 1965 1975 1985 1995 2005 Posts custodians (incl. certified custodians) 10 13.5 13.2 25 30.9 37.5 librarians 70 70.3 63.9 52.1 40 48.4 admin. and tech. staff 20 16.2 22.9 22.9 29.1 14.1 How the library functions and how well it meets the demands of its users also depends on the librarians’ ability to implement their knowledge, their perceptive skills, pro–social attitude and communication skills. Books, journals, audio cassettes, video cassettes, floppy disks or CD–ROMS are but a few means of communication available at libraries’ disposal. Libraries use ...różnymi językami, odmiennymi systemami semiotycznymi (various languages, different semiotic systems). [10] Their use requires appropriate skills and qualifications, knowledge of present–day sources, and the ability to decode them. Now communication is the main part of a librarian’s job. [11]

It is generally believed that a library is a go–between in the communication process which takes place between an author (e.g., of a book or article) and a reader (library user). It happens when, while performing their services, librarians provide readers text in its various manifestations. I think that Dr. Małgorzata Kisilowska is right in saying that a present–day library cannot be perceived only as as a mediator making other people’s communications available to the public. [12] The work of librarians is creative too, e.g., while preparing thematic sets or compiling database librarians use their own knowledge and skills to do jobs; they are the authors of various final products. In this case a library becomes information transmitter.

There are various methods of verbal (conversation, debate) and non–verbal (written or visual) communication. The form and content of communication depend on language competence and factual knowledge of the speaker and listener, their knowledge, qualifications, way of thinking and technical capabilities of those who create the message. All this influences how well the needs of library users are met.

The image of a library is created by its employees, by how effective they are and how they are perceived by the users and the community in which the library functions. The future of librarians is very much in their own hands. The ever–changing environment and the users’ expectations must determine them to constant development. Only in this way can they overcome all sorts of obstacles which are the result of changing circumstances.

Irrespective of where the librarian’s actual workplace is, whether it is the library building visited by readers or his/her own home where the librarian sits in front a computer screen, he/she is going to be an information specialist, knowledge organizer, infobroker, or information manager. Few jobs require employees to be as versatile and ready to educate themselves permanently as librarians today. In order to meet the users’ expectations librarians must first find out about them and understand them, must know the existing sources of information and how to access them, must know how to decode them and pass them on the users in the forms required. The profession will be dominated by scientific information and information techology, which seem to be what future holds in store. The name of the profession itself, its character, its professional status may also change, the way it does in the western world. The profession will enter another stage of its development. But whether there will be a place for librarians depends entirely on us.

Notes

1. A. Łysakowski (ed.), 1956. Bibliotekarstwo naukowe, z uwzgládnieniem dokumentacji naukowo–technicznej. Warszawa: Panstwowe Wydawn. Naukowe, pp. 11–19.

2. M.S. Wielopolska, 1965. “Zagadnienia rozwoju Biblioteki Głównej Politechniki Szczecińskiej w latach 1946–1980,” Zeszyty Naukowe Politechniki Szczecińskiej, nro. 62, pp. 27–45.

3. J. Wojciechowski, 2001. Bibliotekarstwo: Kontynuacje i zmiany. Kraków: Wydaw. Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, p. 63.

4. Wojciechowski, 2001, op.cit., pp. 63–64.

5. Wojciechowski, 2001, op.cit., p. 65.

6. Wojciechowski, 2001, op.cit., p. 66.

7. Wojciechowski, 2001, op.cit., p. 67.

8. A. Jazdon, 2005. “O nowych stanowiskach, specjalnościach i zawodach, czyli czy bibliotekarz to...nadal bibliotekarz?” In: Innowacyjność organizacyjna i zawodowa w bibliotekach: Materiały z konferencji bibliotekarzy województwa lubuskiego ‘Organizacja i zarządzanie biblioteką’. Kalsk, 21–22 września 2004 r., edited by Ewa Mielczarek. Zielona Góra: Pro Libris Wydawnictwo WiMBP im. C. Norwida, p. 46.

9. Socha in Z. Żmigrodzki and R. Fraczek, 1998. Bibliotekarstwo. Warszawa: Wydaw. SBP, p. 383.

10. Wojciechowski, 2001, op.cit., p. 102.

11. M. Kisilowska, 2001. Już nie wiem jak mam do Ciebie mówić czyli komunikacja w bibliotece. Warszawa: Centrum Edukacji Bibliotekarskiej, Informacyjnej i Dokumentacyjnej, p. 125.

12. Kisilowska, 2001, op.cit., p. 21.

References

- Jasińska, T., 1987. “Biblioteka i bibliotekarze w 40–leciu Politechniki Szczecińskiej,” In: Biblioteka i bibliotekarze w 40–leciu Politechniki Szczecińskiej. Pamięci ludzi i zdarzeń. Sesja jubileuszowa 8 kwietnia 1987 roku. (Prace Naukowe Politechniki Szczecińskiej, no. 2) Szczecin: Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Politechniki Szczecińskiej.

- Jazdon, A., 2005. “O nowych stanowiskach, specjalnościach i zawodach, czyli czy bibliotekarz to...nadal bibliotekarz?” In: Innowacyjność organizacyjna i zawodowa w bibliotekach: Materiały z konferencji bibliotekarzy województwa lubuskiego ‘Organizacja i zarządzanie biblioteką’. Kalsk, 21–22 września 2004 r., edited by Ewa Mielczarek. Zielona Góra: Pro Libris Wydawnictwo WiMBP im. C. Norwida.

- Kisilowska, M., 2001. Już nie wiem jak mam do Ciebie mówić czyli komunikacja w bibliotece. Warszawa: Centrum Edukacji Bibliotekarskiej, Informacyjnej i Dokumentacyjnej.

- Kołodziejska, J., 1993. “Wybrane problemy kształcenia bibliotekarzy,” Bibliotekarz 1993, no. 7–8, pp. 20–24.

- Łysakowski, A. (ed.), 1956. Bibliotekarstwo naukowe, z uwzgládnieniem dokumentacji naukowo–technicznej. Warszawa: Panstwowe Wydawn. Naukowe.

- Materska, K., 2002. “Czy profesje informacyjne mają przyszłość?” Biuletyn EBIB, volume 8, number 37, at http://ebib.oss.wroc.pl/2002/37/materska.php (accessed 17 February 2006).

- Siadkowski, S., 1987. “Wykaz pracowników Biblioteki PS w latach 1946–1986,” In: Biblioteka i bibliotekarze w 40–leciu Politechniki Szczecińskiej. Pamięci ludzi i zdarzeń. Sesja jubileuszowa 8 kwietnia 1987 roku. (Prace Naukowe Politechniki Szczecińskiej, no. 2) Szczecin: Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Politechniki Szczecińskiej, pp. 133–150.

- Wielopolska, M.S., 1965. “Zagadnienia rozwoju Biblioteki Głównej Politechniki Szczecińskiej w latach 1946–1980,” Zeszyty Naukowe Politechniki Szczecińskiej, no. 62.

- Wojciechowski, J., 2001. Bibliotekarstwo: Kontynuacje i zmiany. Kraków: Wydaw. Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

- Żmigrodzki, Z. and R. Fraczek, 1998. Bibliotekarstwo. Warszawa: Wydaw. SBP.

- Reports from the Main Library of Szczecin University of Technology (Sprawozdania z pracy Biblioteki Głównej PS), 1973–2005.

About the author

Grażyna Wojsznis is library custodian in charge of Physics and Mathematics Faculty Library, a division of the Main Library of the Szczecin University of Technology.

E–mail: grawoj [at] ps [dot] pl© 2008 Grażyna Wojsznis.