One of three colleges that make up the University of Sierra Leone, Fourah Bay College dates from 1827; it is the oldest college in West Africa. The students number 1,700, including 300 from outside the country. The library occupies a four–story building constructed in 1965. About 140,000 volumes are held, but economic conditions of the nation are so poor at this time that only about 200 books are added each year. Indeed the college has received no government funds for two years. Periodical subscriptions have dropped from 900 titles in 1980 to 90 in 1994. The generosity of donor organizations in Britain and U.S. has maintained 175 other subscriptions, and provided some scholarly books. Interlibrary loan efforts are hampered by a weak communications infrastructure. A promising cooperative venture is being set up by the Economic Commission for Africa and the Pan–African Documentation Information Service. A new hydroelectric power station promises reliable electricity, permitting the installation of air conditioning and the use of electronic media in the library.

During my second visit home in almost 11 years, I spent most of my time visiting educational institutions. Home for me is the Republic of Sierra Leone, a small country in West Africa covering an area of 27,699 square miles (71,740 square kilometers), an area slightly larger than West Virginia. Sierra Leone has a population of 4.1 million and shares common borders with the Republic of Guinea on the north and east, the Republic of Liberia on the southeast, and the Atlantic Ocean, which bounds the country’s western shores. Sierra Leone is known for the British–sponsored settlements created in Freetown for freed and runaway slaves in the late 18th century. Freetown, now the country’s capital, was established on purchased land in 1788. Sierra Leone gained its independence from Great Britain in 1961, and has since been struggling to progress as a developing nation.

![]() Fourah Bay College: A Brief History

Fourah Bay College: A Brief History

Fourah Bay College (FBC) is one of three colleges that make up the University of Sierra Leone. Founded by missionaries in 1827 to train teachers and evangelists, it is Sierra Leone’s first college, and the oldest college in West Africa. In 1867, it affiliated with Durham University in the U.K. and continued thus until it attained independent university status in 1966. FBC is known in West Africa for its high standards in the liberal arts and has gradually expanded its curriculum in the sciences, including areas such as mechanical, electrical, and civil engineering, marine biology and oceanography, and geology. Today, the college has a student body of about 1,700; approximately 300 students are from other African nations. Many of these students are supported through scholarships provided by the Sierra Leone government. The other two colleges making up the University of Sierra Leone are the Njala University College (NUC), founded in 1963 to provide agricultural and home economics education, and the College of Medicine and Allied Health, founded in 1986.

The FBC Library is located in Freetown on Mount Aureol, one of the city’s many hills. A two–mile winding road leads to the campus, which affords some stunning views, most particularly from the library. During my elementary years, I daily passed this college on my way to school and wished that I would one day attend it (instead, I had the good fortune to study in the United States). When I visited the campus in 1994,1 saw it through the eyes of an outsider, and like any inquisitive librarian, wished to examine the college library and analyze its operation.

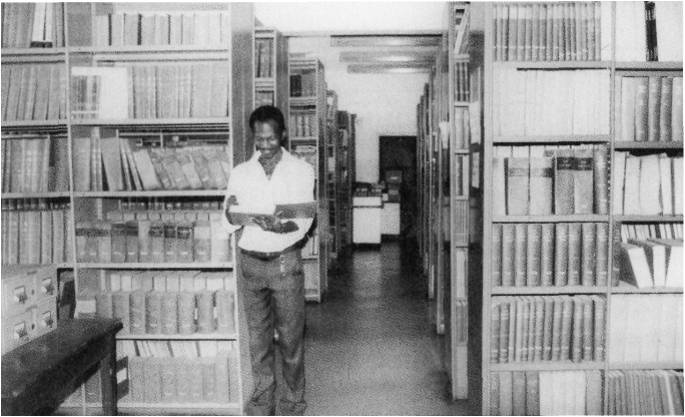

The FBC library is easily recognized because of its central campus location and because it is the most attractive building on campus. The main library moved into its present four–story location in 1965. The first floor includes reference, circulation, acquisitions, and cataloguing departments, along with a few administrative staff offices. The reference area houses a special collection of depository materials. These include historical information on Sierra Leone, statistics generated by the United Nations on Sierra Leone and other West African countries, and literary works by local authors. The library has also been a partial depository since 1961.

The second floor is devoted to periodicals. The library’s collection consists of about 70 percent donations. Many of the donated journals are gifts or discards from other institutions or associations abroad. Journals are arranged according to the Dewey classification system, first by subject and then in alphabetic order by title within each subject. A card catalog system provides access to materials in this order. For example, one would look for the card marked “Economist" among other cards arranged in alphabetical order. Each card has a Dewey call number that directs the patron to the item’s location, either on the display shelves or in the stacks.

The circulating books stack area spans the third and fourth floors, and a special collection of textbooks used at the college is located on the third floor. Students may borrow a maximum of eight books for two weeks. Faculty and staff are limited to a period of five weeks for up to 15 items; they can check out both books and periodicals. Most of the library’s newly acquired books are kept on reserve and can be used only within the library for short periods. At the moment, the library acquires approximately 200 books per year, along with an additional 1,000 received through donations. Currently, the library’s holdings number about 140,000 volumes.

The library is fortunate to have a bindery, located in the basement, where books are repaired and journals bound. This bindery also services libraries from the country’ s other higher educational institutions. The income generated subsidizes the library’s budget.

Collection growth has gradually eaten into reading room area space. Chemical Abstracts, for example, which until its cancellation in 1985 was the library’s most rapidly growing title, took up space equal to that required by several other titles considered together. Although the FBC library has outgrown its space, the librarians are reluctant to engage in a weeding program. Their rationale: few books are acquired annually, and old books are better than no books.

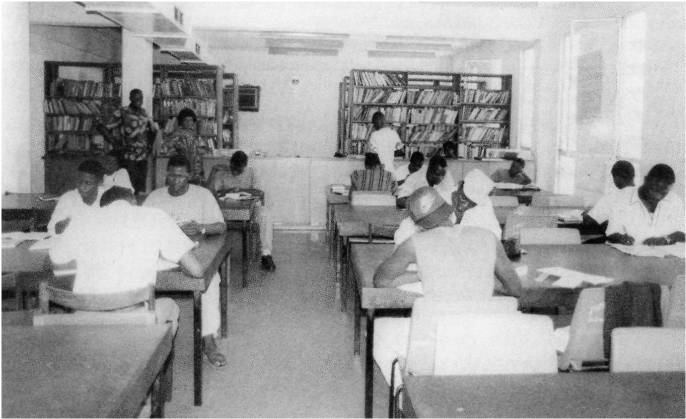

Despite having an attractive facility, and even considering its limited collections, the library’s role has diminished. What used to be a research facility is now primarily a quiet study hall. This is due in part to frequent, unpredictable power failures. We do not realize how much we depend on electricity until it is no longer available. Although the library’s tall windows provide ample light for reading room areas during the day, the stack areas can be very dark. As a result, the library is open only during daylight hours. Without electricity, photocopy and microform machines become useless (and materials such as periodicals on microform inaccessible). Elevators become inoperable. The absence of air conditioning has an immediate impact on the collection—Sierra Leone experiences extreme weather conditions, including humidity that can be detrimental to library materials. Collection deterioration is further aggravated by direct sunlight, rain, and dust from open windows.

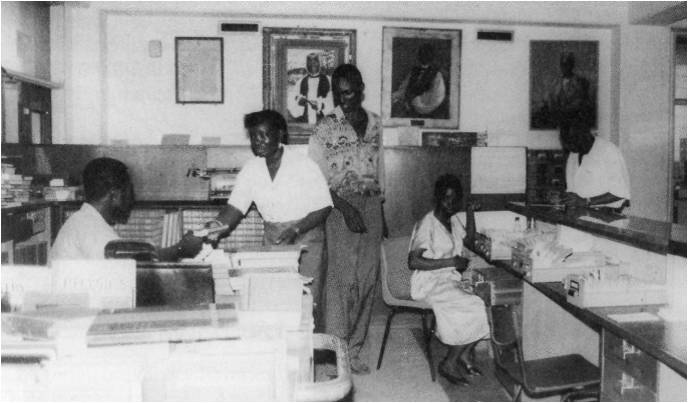

The library’s professional staff consists of librarians trained overseas. Each staffer possesses a library science degree. Titles are similar to those of academic librarians in the United States: for example, Head of Reference, Acquisitions Librarian, and Periodicals Librarian. At the time of this writing, the head librarian is Deanna Thomas, a dynamic individual.

The librarians are helped by clerical staff members who assist with public services at circulation and periodicals, and re–shelve books in the stacks. A clerical staff member typically possesses a college degree, and has worked in a library trainee apprenticeship program while enrolled at FBC’s Institute of Library and Information Studies. This institute, established in 1989, serves to provide training and education for librarians, archivists, and information scientists.

Sierra Leone’s economy has struggled since the country achieved independence in 1961. It is dependent primarily on agriculture and the export of minerals such as diamonds, rutile, and bauxite, although additional foreign trade is afforded by the tourist and fishing industries.

The condition of library resources can directly reflect the economic condition of a country as a whole. The case of the FBC library is not unique among the libraries in developing countries, where “90 percent of library collections are acquired from foreign publishing sources, largely Western Europe and America," and where foreign exchange is required to buy these materials, including spare parts for machinery. [1, p. 107]. Yet currency devaluation has worsened the foreign exchange rate — greatly diminishing purchasing power even in those instances when budgetary allocations are increased.

For the last two years, FBC has not received any government funds, which means that the library’s revenue is dependent on student fees. With this reduced funding, the library has been able to purchase about 200 books a year, down from the 1,500 purchased yearly in the 1970s and 1980s. The numbers concerning periodicals are even more astonishing. In 1980, the library subscribed to 900 titles, and accepted an additional 100 titles as donations. Today, the library subscribes to only 90 titles; 175 more are received as donations.

Among the many generous donors to be commended are the British Council, American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), International Development Research Center (IDRC), World Bank, Ranfurly Library Services, and the United States Information Services (USIS). These organizations have made donations to the FBC library since it opened on the Mount Aureol campus in 1965, and they have seen it through its worst times.

Outstanding contributions have come from the British Council and the AAAS. Since its founding in 1934, the British Council has assisted library development in Africa. Over the years the organization has played several roles, not only “providing textbooks for students and libraries in developing countries at between one–third and one–half of the cost of the original editions,” to training and transforming “of the Council’s own libraries into public libraries, usually conditional however on matching inputs from the local authorities.” [4, p. 17] The AAAS makes arrangements for scientific, scholarly, and professional associations to send their journals to libraries in need.

In May 1992, the Sierra Leone military assumed leadership. Since that time, the country’s economy has stabilized. Recent statistics show an increase in mineral exports of diamonds, rutile, and bauxite from “69 percent in 1989 ... to 93 percent in 1992.” [3, p. 762] These favorable economic changes raise hopes that FBC will receive better funding and that the library will also be a beneficiary. There is hope, too, that the country’s supply of electricity will be more regular. A hydroelectric power station is under construction in Bumbuna, a city about 200 miles east of Freetown. Targeted to begin operating in 1996, the facility should make electricity dependably available throughout Sierra Leone.

An interlibrary loan system has existed informally among the college libraries within FBC, the public libraries, and educational institutions. Shrinking journal collections have made interlibrary loan all the more important for the participating libraries. Its effectiveness is hindered, however, by poor communication services within the country. Postal services are unreliable and both telephone service and road construction are still under development. The FBC engages in interlibrary loan with libraries run by foreign consulates such as the British Council and the American Cultural Center. The British Council’s library in Freetown offers access to a wide range of books, periodicals, audiovisual materials, and now computer software. Students at all educational levels have benefitted from these resources.

There has been much talk in recent years about potential roles for African libraries once the infrastructure for an electronic information system is created. In Sierra Leone, however, librarians have not had much success in compiling national union lists and catalogs because of a perceived lack of national support. “These attempts and failures point to a need for a service that is coordinated." Additional barriers to success: “administrative, financial, and technical problems involved have been those whose solution would have stood a better chance if they had been approached at the national level.” [2, p. 5]

One such cooperative venture is an electronic information service being set up by the Economic Commission for Africa (EGA) and the Pan–African Documentation Information Service (PADIS). The group has planned four sub–regional information and documentation centers in the Central, Southeast, West, and North African regions, to which national centers would be linked. “PADIS was created in 1980 to establish data banks and to provide a computerized information service ... and at the moment Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, and Senegal have operational national centers.” [2, p. 9] There is hope that once the FBC library has its collection available online, backed by authorities who can encourage and support national and international systems designed for effective management, it will have a chance to become linked to PADIS as one of the national centers in West Africa. Becoming a part of a regional cooperative organization will increase resource sharing among libraries in Africa, as well as with other developed countries.

Many African libraries are trying to catch up with the technological revolution. The FBC library does not have a fax machine, which is standard in most libraries today. Libraries without computer technology are realizing that “it will become imperative sooner or later, in order to ensure accessibility to the new formats in which the information of the future will be packaged. Those unable or unwilling to make adjustments face the prospect of becoming obsolescent.” [1, p. 108]

With the income generated from its bindery, the FBC library recently purchased an electronic database management system. The installation and implementation is scheduled to occur over a two–year period. The hope is that it will be fully operational about the same time that the hydroelectric power station is ready.

Reliable electric power in Freetown will bring solutions to some major problems at the FBC library. Library hours can be extended, and air–conditioning will slow the physical deterioration of the collection. One problem that will not be easily solved is that of acquiring more extensive, updated collections. This is where other libraries can help.

As modern libraries in the developed nations change from print formats to electronic formats, librarians might consider giving the print materials new life by making them available to libraries in the developing nations.

I encourage all citizens of developing nations who live in developed nations to do some fund–raising for the library of their alma mater. “Donate a book or $5” is a reasonable theme with which to begin; the money can be used for shipping and handling of materials. This resource sharing can benefit the developing nation’s present and future generations.

Thanks to Deanna Thomas and the staff at the Fourah Bay College Library, who work in the service of their students, faculty, and all of Africa. I appreciate the encouragement and suggestions of my colleagues at the College of Staten Island Library, New York.

1. Banjo, A. Olugboyega. “Library and Information Services in a Changing World: An African Point of View.” International Library Review 23 (1991): 103–110.

2 Boadi, Benzies Y. “The Information Sector in the Economic Development in Africa: The Potential Role for Libraries.” Paper presented at IFLA General Conference, Munich, 1981; African Section, Regional Activities Division. (ERIC Document ED239648, August 1983.)

3 Funna, Soule M. “Sierra Leone: Economy.” la Africa South of the Sahara 1994. 23rd ed. London: Europa Publications, 1993. Pp. 761–764.

4 Roche, Gillian. “Library Development Worldwide: The Role of the British Council.” Paper presented at the IFLA General Conference, Brighton, 1987; Division of Regional Activities. (ERIC Document 300007 August 1987.)

|

| Figure 1 |

|

| Figure 2 |

|

| Figure 3 |

Wilma L. Jones is Assistant Professor and Head of Periodicals at the College of Staten Island, City University of New York. She has master’s degrees in English and Library and Information Science from Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois. She is a native of Sierra Leone, and has recently returned from a visit there.

© 1995 Wilma L. Jones.

Citation

Jones, Wilma L. “Profile of an African Library: Fourah Bay College,” Third World Libraries, Volume 5, Number 2 (Spring 1995).