Afghanistan, a landlocked country situated in the heart of Asia, has common borders with Pakistan, Iran, Turkmanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and China. Its history goes back at least as far as 1500 BC, and includes such figures as Darius and Alexander the Great. The population is estimated to be 17,000,000, and is made up of such ethnic groups as Tadjiks, Pashtuns Hasaras, and Uzbeks. The two official languages are Dari and Pushtu. Kabul is the capital. Islam is the state religion.

In 1978 Afghanistan was occupied by forces backed by the USSR. Years of severe fighting ensued, as vaarious native Islamic groups (with backing from other countries) strove to oust the Soviets and their supporters, and also fought among themselves. The years of warfare were destructive. Many of the nation’s educated citizens were killed, or emigrated. Cultural and social organizations were demolished, and their buildings ruined. The National Museum no longer exists. The National Archives was partly demolished, its contents stolen and sold abroad. The contents of public libraries, and of the library of the Academy of Sciences, were stolen and sold by weight in the book markets of Kabul, as well as in Pakistan.

The present article is about Kabul University Library, which I served for more than ten years as director, and modernized. Before 1978 this library was unique in the region. Researchers from Iran, Tajikistan, Arabian countries, Pakistan, and India came to use its rich and rare materials. It was well equiped, with holdings in English, Russian, French, German, and Arabic in all fields of science. It was also strong in the humanities and social sciences. Its Afghanistan Studies Section was unique in the world.

During the civil war I escaped from Kabul and sought refuge in northern parts of Afghanistan. Then, rather dramatically, I was asked to return clandestinely to Kabul, and found an opportunity to visit the ruined Kabul University Library. Thus, I can give you some of the impressions I gained there.

In Afghanistan, everyone knows the name of Said Mansoor Nadri. He is the spiritual leader of the Ismailia (Shiite) faction. Because of the armed groups he controls, he is powerful in a region covering the Kayaan valley, Baghallan, and some other parts of northern Afghanistan. Kind and generous, he paid for the education of many poor children — sometimes even sending them to universities abroad. Recently in established a new and modern library in Kabul, as well as a university in the Baghallan province.

While the fundamentalist Islamic groups held power in Afghanistan, and I was — like many of the other educated people of Afghanistan — a refugee in the northern parts of the country, I met Nadri in Baghallan. He suggested that I go to Kabul, covertly, to find and sort valuable materials of the Amir Khusrou Balkhi Library — the library he had founded — and transfer them to Baghallan. I took this as an order, and joined a caravan moving toward Kabul. Although I reached the city easily, I was confined to a camp of a certain paramilitary group, and my movements were restricted. Under these circumstances, I started my mission in the Amir Khusrou Balkhi Library.

The Amir Khusrou Balkhi Library had more than 20,000 items, consisting of books, journals, newspapers, documents, and rare books and journals. Its primary strength was in history, literature, geography, and religion. The Afghanistan Studies collection was its special collection, and was second only to that in the Kabul University Library. Fortunately, the Balkhi Library had been left untouched during the fighting between rival armed groups. We started searching through and sorting the valuable national bibliography materials, as well as the rare journals, newspapers, and manuscripts.

This took us about a week. As we finished the work and got ready to go back to Baghallan, another mission emerged for me. The president of Kabul University, a disciple of Nadri and one of the persons educated with his encouragement and monetary support, contacted Nadri and obtained permission for me to visit the Kabul University Library.

The Kabul University Library was established in 1932. At first it contained 5,000 booksm and had three librarians, two assistants, and a very limited budget. By 1992, it had fifty librarians, fifty clerical workers, and thirty blue–collar workers, as well as mechanics and other craftsmen. Its 200,000 books included 5,000 manuscripts, 10,000 books on Afghanistan Studies, 10,000 bound volumes of periodicals, 3,000 rare books, 10,000 electronic materials, 2,000 photo albums, 5,000 calligraphic specimens, and a strong collection of national archival and documentary materials. A collection of old national books donated by Professor Abdul Haque Batab was unique.

The Kabul University Library’s collections were classified by the Library of Congress system. There was modern electronic and photographic equipment from the United States, as well as a modern conservation centre.

Occupying an area of 500 by 100 meters, in two floors, the library was furnished with modern, heating, lighting, and telephone systems, and with soundproof rooms. Although it served the university, it was also the National Library of Afghanistan. In addition to being the focal point for United Nations publications, it owned the Union Catalogue for the city of Kabul’s libraries, as well as for other major cities of Afghanistan.

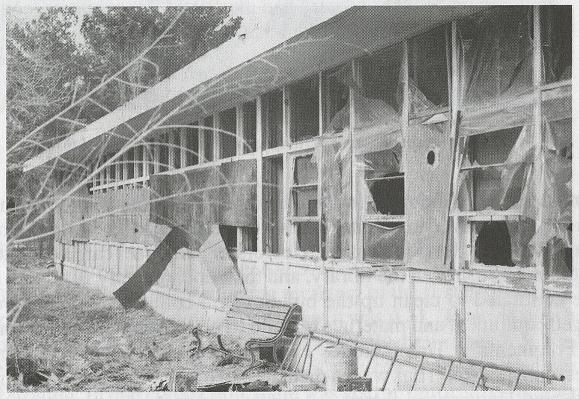

It was, then, after an absence of three years that I revisted the University Library. Its surroundings had changed beyond recognition. There were a lot of holes in the lawn. Trees and decorative bushes, untended, were growing wild. Even finding the path to the library was difficult. The large and proud building had been ruined, humbled to the dust. I counted twenty–five holes in the walls and roof. Everywhere were big chunks of concrete and broken pieces of roofing, lighting, glass, the heating system, shelving, and cabinets. It was hard for us to move from one place to another. The library’s large and beautiful hall had become a mere path through rubble.

|

| Outside of Kabul University Library |

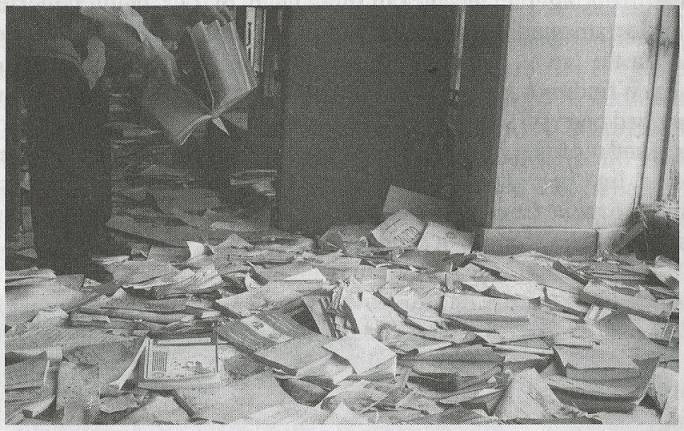

The library’s valuable materials had been sold on the national and international book markets. Some of the books and periodicals had been moved to military bases. The signs of burning, and destruction by weapons, were obvious. We saw where periodicals had been burned, and found a mass of ashes of manuscripts, rare books, and materials from the Afghanistan Studies Collection. The electronic and photographic collections, the national books and documents, and the collection donated by Professor Abdul Haque Batab had been sent to book markets, with only some charred materials left behind. Library materials which the vandals could not transfer to book markets were scattered all around.

We started to work, but we scarcely knew how to go about it, or where to start. We shoveled out dust, ashes, and broken pieces of concrete. We collected any salvagable books, periodicals, and miscellaneous materials. We replaced and set upright any remaining shelves, card catalogues, and other equipment found reasonably intact. We closed the holes in the walls and roof, and covered broken doors and windows. In the meantime, the books and other materials which had been moved to military bases were returned to the library. Gradually these restorative efforts increased. University personnel came back to work. Photographers rushed to the library, and took documentary films and photos. As we continued to clean up the building, we collected fragments of war–damaged equipment and materials to build “The Museum of the Library War–Time Fragments.” This included charred books and periodicals, damaged shelves, and the like. Thus we reached the end of the first phase of our mission at the Kabul University Library.

|

| Remains of burned bound periodicals at Kabul University Library |

The second phase was that I had to explain to the university president what happened to the library materials. Unfortunately, during the first phase of our work, as we searched for valuable manuscripts, national books, national archives documents, rare books, electronic materials, calligraphic specimens, and the like, we had found nothing valuable, and so had nothing to offer to the president. The library need to be rebuilt from the ground up. The only fruitful thing to come out of our work was that I participated in recording a videotape documentary in which I gave my over–all view of the past, present, and future of the Kabul University Library, and suggested methods for rebuilding and strengthening it. But the present environment in Kabul is not conducive to cultural restoration. The fundamentalist Islamic groups have a threatening way of ruling Consequently, I had no hope that things might improve, and no desire to stay longer and watch these people controlling cultural and scientific organisations. So I left — perhaps forever — the library which I had nurtured as though it were my child.

The cultural heritage of Afghanistan disappears periodically because of the destruction wrought by barbarians, but it is never entirely eliminated. Somehow our rich and strong heritage will survive, in one place or another. As I have explained, during the recent fighting much of our cultural heritage was transferred to the national and international book markets. But this means that it is at least alive and gathered somewhere, whether inside the country or outside. We are not downcast, and we have not lost courage. Our history has seen many conquerors, and our cultural heritage has frequently been moved to other cultural centres, but it has never been destroyed utterly. In one way or another, it has been restored. Our history shows the destuctive power of Genghis Khan, Tamerlane, the Mogul Empire, the English, and now the Islamic fundamentalists. But sooner or later another national hero will emerge, and Afghanistan will again become the crossroads between eastern and western civilisation. But this time brighter than ever.

Abdul Rasoul Rahin is President, Afghanistan Cutural Association, Hägersten, Sweden.

© 1998, Abdul Rasoul Rahin.