The French National Library: A Special Report

Introduction

A few months ago (on 9 October, 1998), the French National Library (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, BNF *) opened to the public the final portion of the François Mitterand/Tolbiac Library in the 13th arrondissement (Left Bank) of Paris. This event marked not just the opening of a new building but also the culmination of a program to provide adequate space and to reorganize a great institution in preparation for meeting the challenges of “The Information Age.” It seems appropriate to take note of this remarkable accomplishment. An entire book, or perhaps several, could be devoted to the topic, but the present brief report concentrates on how the BNF has faced and solved its problems of space—leaving it to others to deal with equally important questions of collections, service, information technology, finance and administration, etc. Intersecting with issues of space for readers and space for collections, it deals mainly with the François Mitterand/Tolbiac Library, because it is the newest, largest, and most important of the BNF’s facilities. (There are seven other sites. Final steps in giving the BNF adequate space for the century—many renovations at certain of them—are still in the developmental stage, but are expected to be realized within two or three years.)

This article, prepared especially for those who have not yet seen the new building (and who may not read French) attempts to provide an overall description of what some call “the billion dollar library”.

Supplementing the text are four additional sections which may be helpful to the reader:

- 1) some photographs of the structure and floor plans of the upper and lower garden levels;

- 2) a brief chronology of the BNF (emphasizing the 20th century);

- 3) some statistics;

- 4) and a selected bibliography of useful works in English.

Spatial Growth at the BNF

Although the royal library of the French kings traces its origin back to the 15th century, for a long time it was an itinerant collection, moving from one royal palace to another. Not until the reign of Louis XIV did Colbert bring it to the heart of Paris; in 1666 it was installed in two houses he owned on Rue Vivienne and then moved to adjacent properties along the Rue des Petits Champs.

During and after the French Revolution (the library was renamed Bibliothèque Nationale in 1792) there were proposals to construct a new building in another part of Paris, but this did not happen. Finally in 1859 the architect Henri Labrouste (1801‐1875) presented a building plan for the BN. Its major features were the complete remodeling of the old quarters and the construction of a new building at the corner of the Rue de Richelieu and the Rue de Petits Champs. The new structure would contain the now famous main reading room (Salle Labrouste), four adjoining stack levels, and other facilities.

The next period of significant expansion took place during the administration (1930‐1964) of Julien Cain (1887‐1974). Under the direction of two architects (Michel Roux‐Spitz, followed by André Chatelin) a new room for catalogs and bibliographies was built under the Salle Labrouste, two levels were added to the stack, and renovation of older structures resulted in new or improved quarters for Manuscripts and other departments. Even though five additional stack levels were added later (1954‐1959) above the existing stacks, space for the growing collection remained inadequate. As a remedy, an offsite storage facility was built at Versailles; the first module, opened in 1934, was followed by two more (1954 and 1971).

The construction of a new building across the Rue de Richelieu for the Department of Music in 1964 and the transfer of units for technical processes and information technology to renovated facilities built around the Galerie Colbert across the Rue Vivienne brought additional relief to the spatial pressures, even though these new additions were outside the main Richelieu complex (quadrilatère Richelieu).

But by the 1980s the BN’s facilities had again reached the saturation point, and the Library had, once more, to face the problem of insufficient space for its collections, its staff, and its readers (shortly after the BN opened in the morning, every seat in Labrouste’s elegant reading room was occupied, and the lines of those waiting for a place would stretch into the hall).

Several directors of the BN called attention to this situation, and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie proposed a second building (“Bibliothèque Nationale bis”). The government appeared ready to take action, but unexpectedly President François Mitterand, in his address to the nation on 14 July 1988, called for a “very large library of an entirely new type.” With this a new and separate institution, soon to be named the Bibliothèque de France was born; four months later a report prepared by Patrice Cahart and Michel Melot made recommendations for a building with capacity for many more readers than the BN, for an expanded acquisition program, for the use of information technology, for the re‐distribution of the BN’s collections, etc. Following the pattern of other large scale cultural projects (grands projets) of the Mitterand years (e.g., the “new Louvre” and a new opera house at the Place de la Bastille), a new independent agency (Etablissement Public de la Bibliothèque de France, EPBF) was given responsibility for construction of the building, for organizing its contents in association with the BN, and for implementing other aspects of the report. Each institution (BN and EPBF) remained independent, however; after some early tensions, a spirit of cooperation prevailed (e.g., the Bibliothèque de France accomplished some of its goals by supplying funding to the BN). The EPBF operated from 1990 to the end of 1993, when it was merged with the Bibliothèque Nationale to create the present French National Library (BNF).

BNF: The New Building at the François Mitterand Site

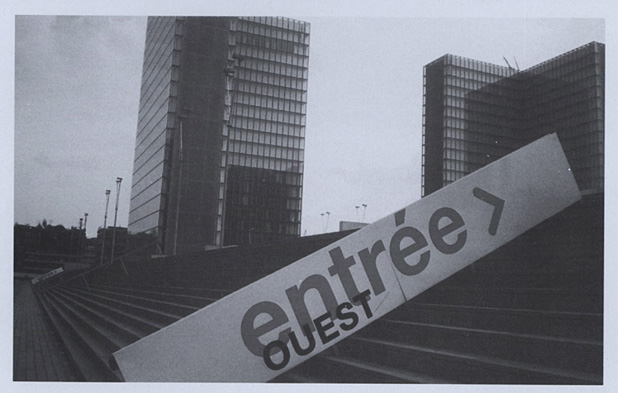

photographs by Marilyn Lester

The François Mitterand/Tolbiac Library

Following the submission of the Cahart/Melot report, the Bibliothèque de France organized an international design competition for its new building. In 1989 the jury reduced over 200 proposals to four finalists, from which President Mitterand chose the one submitted by a young French architect, Dominique Perrault.

It is quite easy to understand the basic elements of the building proposed by Perrault and now designated the François Mitterand/Tolbiac Library (see the photographs and floor plans included above):

- (1) a two floor rectangular base (with the two long sides parallel to the Seine River), surmounted by a plaza

- (2) a large sunken garden occupying the hollow center of the rectangular base and level with its lower floor

- (3) four angular towers rising from the four corners of the plaza, like four open books facing each other

With but little modification (e.g., a slight lowering of the height of the towers and changes in the dimensions of the garden), this is the exterior of the building one sees today. Once the site (then occupied by warehouses and railroad yards) was cleared, construction, begun in 1992, moved forward very rapidly, and the building was completed in March 1995; it was, however, opened to readers in two successive stages.

On the other hand, considerable controversy arose over the use of the interior space. One criticism was that the towers would not afford a suitable environment for books; another was that users would not like having reading rooms below the plaza level, even though much natural light would enter from the large glass panels facing the sunken garden.

By far the most serious of the objections centered around the collection itself. It was originally proposed to transfer to the new library only the BN’s post‐1945 holdings (about 3,000,000 volumes), but an immense protest from historians and other scholars to such a chronological division quickly led to a change; all of the BN’s books and journals from both the Richelieu and Versailles sites (estimated to total more than 10,000,000 volumes) would go to the new library, as would its audiovisual holdings. The special collections of music, maps and plans, etc. would remain at the Richelieu site. To provide space for this greatly enlarged collection the architect reworked plans for the base, so that 50 to 60% of the collection would be housed there, and the remainder in the towers. Perrault also modified each tower’s interior; it consists of 18 levels, the lower seven configured for staff use and the upper eleven fitted with shelving for books and journals. Each tower has independent access from the plaza level (primarily for staff), although the elevators do run to the building’s lowest floor.

These decisions resulted in the library’s two podium‐based levels consisting of concentric rectangles, as follows: corridors facing the garden, for circulation of users and staff; reading rooms; stacks and staff areas; and finally a mechanical and equipment zone. The periphery of the lower level also contains entries for vehicles and parking space (which in the future could be converted into additional stack areas).

It also became clear that the concept of a single library “open to all” was not feasible, given the extent and unique character of the BN’s collections. This was resolved by having two different libraries which would operate on the building’s two levels. The upper garden level houses an entirely new public library (open to anyone over 16 years of age). It does not contain strictly popular publications, but rather those which may interest “intelligent laypersons” and first level university students. The lower garden level contains a research library, successor to the BN, providing access to its vast patrimonial collections of books, journals, and audiovisual items; it can accommodate many more accredited researchers than the two main reading rooms at the Richelieu site. Furthermore, the BN’s old organization of its resources by format (books, periodicals, manuscripts, maps and plans, etc.) has given way (insofar as print collections go) to four thematic or subject departments (plus another for audiovisual material), each of which has responsibility for its area in both libraries.

The specific layout of the two floors is not, however, identical, as the following discussion and floor plans indicate.

The Public Library (Upper Garden Level)

The François Mitterand/Tolbiac Library has two main entrances, at the eastern and western ends of the plaza. Ramps lead down to the Upper Garden Level, which contains the public library, as well as facilities and services open to the general public. These include two large reception halls (containing cloakrooms, general information desks, and registration areas), a bookstore, an orientation center, two exhibition galleries, and a small cafeteria; there are also two auditoriums (seating 350 and 200) and six meeting rooms.

Two corridors, running east/west, connect the reception halls and provide access to the public library’s ten reading rooms. Each contains an open shelf collection (arranged by Dewey Decimal Classification), several hundred current serials, different types of seating for readers (1645 places in all), terminals for the online catalog, and professional staff to assist readers. The collection, entirely new for the public library, has been selected to emphasize contemporary interests and issues as well as standard works, but is encyclopedic in coverage. It came to about 180,000 volumes when the library opened in December 1996 and will more than double in the next few years. The audiovisual holdings cut across all disciplines and supplement the print materials with records, videos, microforms, multi‐media items, and digitized texts and images.

The reading rooms are as follows:

- Science and Technology (Room C)

Seats for 220 readers. The collection will reach 50,000 volumes with 400 serials currently received.

- Law, Economics, Politics (Room D)

Seats for 287 readers. The collection will reach 60,000 volumes with 500 serials currently received. (This room includes materials on business and holdings of government publications.)

- Literature and Art (Rooms E, F, G, H)

Seats for 560 readers. The collection will reach 120,000 volumes with 750 serials currently received.

- Philosophy, History, Social Science (Room J)

Seats for 276 readers. The collection will reach 65,000 volumes with 500 serials currently received. (This room includes geography, anthropology, sociology, psychology, education, and religion.)

- Audiovisual (Room B)

Seats for 152 readers. Holdings include a/v items and a 5,000 volume reference collection with 300 serials currently received in the fields of music, cinema, television, radio, and mass media.

- Reference (Room I)

Seats for 70 readers. The collection comes to 8,000 volumes of bibliographical tools as well as dictionaries, encyclopedias, etc., with 100 serials currently received.

- Newspapers (Room A)

Seats for 80 readers. The collection includes over 300 current French and foreign newspapers and general magazines. There are 1,500 volumes of reference works on the press and related areas.

| |||

| Reading Rooms (Upper Level) | |||

| A | Newspapers and Periodicals | ||

| B | Audiovisual Materials | ||

| C | Science and Technology | ||

| D | Law, Economics, Politics | ||

| E, F, G, H | Literature and Art | ||

| I | Reference Room | ||

| J | Philosophy, History, Social Science | ||

| This level is for the general public (16 years old and over) | |||

The Research Library (Lower Garden Level)

Reached by elevators and escalators at each corner of the Upper Garden Level, the Research Library occupies the entire lower level and looks out onto the garden floor. Unlike the upper level, it has no area open to the general public; facilities and services are available only to accredited researchers. The basic layout is, however, the same: a rectangular corridor facing the garden providing access to 14 reading rooms along both sides and both ends of the building (the Rare Book Room is on a mezzanine).

Scholars used to working at the Bibliothèque Nationale’s Richelieu complex will find that not only has the number of reading rooms increased but their nature has changed. The two main rooms there (Salle Labrouste and Salle Ovale) were devoted to books and to periodicals respectively; at Tolbiac eleven of the fourteen rooms are thematic in nature. These subject reading rooms contain entirely new open shelf collections (arranged by Dewey Decimal Classification) and several thousand current serials. In all, the collections will eventually reach 400,000 volumes, although they came to considerably less than that when the library opened in 1998. The number of seats for readers increased greatly, going from 600 at Richelieu to about 1800 at Tolbiac.

The reading rooms are as follows:

- Science and Technology (Rooms R, S)

Seats for 150 readers. The open shelf collection will reach 72,000 volumes with 1,800 serials currently received.

- Law, Economics, Politics (Rooms N, O#41;

Seats for 265 readers. The open shelf collection will reach 51,000 volumes with 800 serials currently received. (These rooms include official publications and many newspapers formerly housed at the Annex in Versailles.)

- Literature and Art (Rooms T, U, V, W)

Seats for 372 readers. The open shelf collection will reach 115,000 volumes with 800 serials currently received. (These rooms include library and information science, history of the book, publishing, book arts, and children’s literature.

- Philosophy, History, Social Science (Rooms K, L, M)

Seats for 425 readers. The open shelf collection will reach 83,000 volumes with 700 serials currently received. (These rooms include geography, ethnology, sociology, and religion.)

- Audiovisual (Room P)

Seats for 263 readers. This room contains about 1,000,000 items coming from the BN’s Sound Archive and Audiovisual Department (mainly recordings) and from the National Audiovisual Institute (INA) (mainly radio and television programs), plus over 300,000 digitized images. The open shelf collection will reach 22,000 volumes and 500 serials currently in the fields of cinema, radio, television, music, and related areas.

- Bibliographic Research (Room X)

Seats for 142 readers. The open shelf collection consists of about 30,000 volumes, for the most part the holdings of the old catalog and bibliography room at the Richelieu site, but enhanced by new acquisitions in areas under‐represented there.

- Rare Book (Room Y)

Seats for 48 readers. An open shelf collection containing about 8,000 volumes on the history of the book, printing, illustrated books, book arts, etc. The closed stacks contain over 200,000 volumes (transferred from the Réserve des livres rares et précieux at the Richelieu site): incunabula, books printed in the 16th and 17th centuries, limited editions, fine bindings, etc.

| |||

| Reading Rooms (Lower Level) | |||

| K, L, M | Philosophy, History, Social Science | ||

| N, O | Law, Economics, Politics | ||

| P | Audiovisual Materials | ||

| R, S | Science and Technology | ||

| T, U, V, W | Literature and Art | ||

| X | Bibliographical Research | ||

| Y | Rare Books | ||

| This level is for accredited researchers (e.g., those who formerly had access to the BN) | |||

But it was, perhaps, easier to decide to create a new open shelf collection for the Research Library than to determine which part of the BN’s vast holdings—the nation’s patrimonial collection—would come to the new building. Unlike the British Library, which had hoped to centralize all of its London holdings in the new building at St. Pancras, in France it was apparently never intended that the EPBF would take over all of the BN’s resources. As already indicated, the first proposal to transfer only the post‐1945 acquisitions was rejected almost immediately in favor of bringing Richelieu’s books and journals across the Seine (in what may have been the biggest book move in history; it required precise planning and organization and took from spring 1998 to the end of the year) as well as transporting holdings (mainly journals and newspapers) from the Versailles Annex to Tolbiac. Some additional decisions needed to be made—e.g., should all of the less used items from Versailles be transferred, or should some go directly to a new offsite storage facility? Which institution should have audiovisual material? Should manuscripts and closely associated rare books be kept together under one roof?

The merger of the BN and the EPBF in January 1994 probably helped the decision‐making process as a philosophy of “one library, two sites” was articulated. Tolbiac would contain printed, audiovisual and digitized items, while five “specialized collections” (music; maps and plans; prints and photographs; coins, medals, and antiquities; and manuscripts) would remain at Richelieu and be joined by a sixth (performing arts) still in the Arsenal building.

More Than a Hospital for the Book

For some time the BNF, like other research libraries, has been concerned with the problems of its deteriorating collections (estimated by some to exceed several million pages). In the 1980s two conservation centers were established outside of Paris: one at Sablé for deacidification of print‐on‐paper items and for restoration work and one at Provins for treating newspapers and serials. Thus it is not surprising that plans for the Bibliothèque de France (EPBF) included not only full climate control in the new library but also a large offsite facility which could not only do preservation and conservation of books and other items but also store them under optimum conditions (this is possibly the least known feature of the program for the “very large library”). To house the new unit Dominique Perrault designed a strictly functional building, which was constructed in the eastern suburb of Marne‐la‐Vallée and opened in 1997. His plan also permits the construction for additional storage modules.

The “hospital for the book” (officially known as the Technical Center for the Book) consists of two side by side units, each shaped like the letter E, with a common “interior street” joining them and running the full length of the building, which the BNF and the Ministry of Higher Education and Research share.

The BNF’s part of the building consists of three principal areas: (1) offices, canteen, auditorium and other administrative space, (2) laboratories for microfilming, for restoration, for deacidification, for converting items to digital format, and (3) a storage area, part of which has very high shelving (10 meters) for storage of little used material. Present policy calls for storing a “back up” copy of all new French accessions (about 50,000 books and thousands of other items per year), utilizing for this purpose the second copy received by legal deposit. Consequently, should the first copy at the Tolbiac building disappear or be worn out, another can be created as a replacement. It is interesting to note that, although little used items stored at the Versailles Annex went to the stacks at Tolbiac, plans for the future include transfer of this kind of publication to Marne‐la‐Vallée, thus extending the shelf capacity for a longer period. It is estimated, for example, that the combined storage capacity at Tolbiac and Marne‐la‐Vallée might provide for 30,000,000 volumes.

Renewal and Renovation at Richelieu

In a previous section this report summarized briefly the expansion of the Bibliothèque Nationale quarters since the mid‐19th century. Simply stated, this had involved first connecting and then expanding buildings, old and new—resulting in the Richelieu complex (quadrilatère Richelieu) we now recognize. Since there was no room for further construction within this block, later expansion took place across the Rue de Richelieu to the west and across the Rue Vivienne to the east. Notwithstanding, by the 1980s all facilities were stretched to the break point—with no real solution in sight. The proposal for a new library (leading to the Bibliothèque de France project) was probably influenced by the space situation at the BN, although precisely in what ways no one knows.

|

| Diagram of Richelieu Complex (“Quadrilatère Richelieu”) |

As the new library began to take shape, in form and in function, thinking about what had become the Richelieu‐Vivienne‐Louvois complex underwent a significant change, because it was realized that the move of all the BN’s books, journals and audiovisual materials across the Seine would free up a very large amount of space (including two large reading rooms and stacks housing millions of volumes). What institution would take over this space and for what purpose?

At this point the story become inextricable interwoven with a series of proposals (made since the early 1980s) to establish a National Institute of Art History (INHA) as both a teaching and researching organization, to which (in most proposals) a great art library would be attached. By the early 1990s some persons were suggesting that the five special collections (prints and photographs, etc.) remaining at the Richelieu could also form a valuable part of the new library. This would have been, in effect, a dismemberment of the Bibliothèque Nationale—its printed and audiovisual collections going to the new Bibliothèque de France (EPBF) and the remainder to the library of INHA. However, the 1994 merger of the BN and EPBF to for the BNF which almost immediately proclaimed itself “one library, two [main] sites” effectively blocked this idea.

However, another period of reports, studies, proposals and counter proposals followed; some preliminary decisions were given up or reversed. For example, at one point it was suggested that the entire Arsenal Library be brought to the Richelieu complex. While it is impossible for an outside observer to trace all issues debated, it appeared likely that involvement of several ministries (culture, higher education and research, budget) further complicated matters.

By late 1998 general decisions on the future use of the space at the Richelieu complex seemed fixed. An institute of art history would come into being and utilize the building at 2‐4 Rue Vivienne for its classrooms and offices (to open in 2002); a new library to be formed by the merging of several existing Parisian collections would open, at a later date, using the Salle Labrouste and portions of the adjacent stacks. The BNF would continue to occupy the remainder of the Richelieu complex, except for areas shared with INHA for common administrative services.

Further study and specific proposals now come under what is called the Richelieu Project. The first step was to create a common reference room (replacing the bibliography and catalog room beneath the Salle Labrouste) in the Salle Ovale; it opened in this new role late in 1998 with seats for 35 readers and a collection of 7,000 volumes. At present, it also serves researchers utilizing the Bibliothèque d’art et d’archéology, given to the University of Paris by Jacques Doucet and moved to Richelieu complex in 1993. Preliminary plans call for each of the four departments in the central buildings (Maps; Manuscripts; Coins; Medals and Antiquities; Prints and Photographs) to expand into space adjoining their present quarters. The Department of Performing Arts will leave the Arsenal building to become the sixth specialized collection at Richelieu, while maintaining its branch at the Maison Jean Vilar in Avignon. The Department of Music, remaining in the Louvois building, will similarly retain its branch at the Opera (Palais Garnier). The Richelieu Project will also plan for the rehabilitation of the Arsenal building following the departure of Performing Arts. Execution of these changes will take place over the next several years.

The Arsenal Library

For several centuries the Arsenal building had housed the armory of the city of Paris, but in the 18th century it became the residence of the Marquis de Paulmy; a great bibliophile, he formed a library which was sold to the Comte d’Artois at the time of the French Revolution. A few years later it was nationalized and flourished throughout the 19th century as an independent cultural institution, especially as a center of literary soirées. In 1934 the Arsenal Library was transferred to the Bibliothèque Nationale, becoming one of its ten departments.

But the story of this library in the 20th century is also intertwined with another of the BN’s departments. In 1920 the great collector Auguste Rondel gave to the nation his vast holdings of theatrical material, which since 1925 has also been housed in the Arsenal building. In 1976 they formed the core resources of a new Department of Performing Arts.

The collections of the two departments have of course continued to grow (aided in part by legal deposit of relevant publications): the Arsenal Library now has well over 1,000,000 volumes and the Department of Performing Arts several million pieces. As a monument, the Arsenal building could not be expanded, and the problems of crowded stacks and insufficient space for readers and staff has become more and more acute; inadequate maintenance of the building itself further exacerbated the problem. One suggestion, made over the years, was to provide new facilities beneath the surrounding grounds. In the mid‐1990s there was an attempt to transfer the Arsenal building to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a site for its archives, presumably on the assumption that both collections could be moved to the Richelieu site. When Friends of Arsenal Library and others objected strongly, the idea was dropped.

The various proposals for renewal and renovation at the Richelieu complex have finally resulted in two apparently final decisions: (1) moving the Department of Performing Arts from the Arsenal building to join the other five special collections and (2) leaving the Arsenal Library where it is. Renovation of the Arsenal building (under the Richelieu Project) will obviously include modernizing the electrical and plumbing systems, but as of late 1998 more specific plans had not been prepared.

Conclusion

Many changes have taken place in the French National Library (BNF) in recent years. This report deals with only one of them: spatial growth. This expansion consisted first of constructing a very large new library (the Bibliothèque François Mitterand/Tolbiac with an offsite storage facility), completed in 1998, and second of rehabilitating of its older facilities (still in progress). The ambitious goal of the program was to provide one of the five largest libraries in the western world with completely adequate and modern facilities. To make such plans is a bold undertaking; to bring them to fruition in little more than a decade is indeed a spectacular accomplishment.

This report may bring to mind two earlier attempts to solve spatial problems at very large libraries: Julien Cain’s work at the Bibliothèque Nationale and Keyes D. Metcalf’s program at the Harvard University Library. Since both efforts took place in the 1930s, it would be interesting to know whether Cain was aware of what Metcalf was proposing in Cambridge and vice versa. Nevertheless, we can see several interesting parallels. First, the issue of space was one which a new director had to face early in his administration; second, the depression of the 1930s made it all but impossible to propose a completely new building (hence the concept of retaining indefinitely the main building of that period as a “flagship” library); third, the problem of space for the collection was to be solved, in part, by an offsite storage facility.

How can we summarize what the French accomplished in the 1990s? They avoided the threatened dismemberment of the Bibliothèque Nationale as well as the possible co‐existence of two rival institutions. They now have a national library with five times as many seats for readers, with sufficient stack space for many years, and with greatly expanded and improved accommodations for staff. Just as Metcalf neatly summarized his proposal for the Harvard library in the phrase “coordinated decentralization,” so the French have also come up with one: “one library, two sites,” which, if not strictly accurate (the BNF operates at eight sites, five of them open to the public), does wrap up their recent achievement.

During the construction of the new building at Tolbiac, I remarked on its high cost to an Argentine friend, long resident in Paris. “That’s true,” he replied, with just a trace of a smile, “it is expensive. But I think the French have their priorities right. It is better to build a great library than another aircraft carrier.”

NOTE:

* Although the acronym is generally written BnF in French, this article has chosen to follow American practice of “all caps,” as in LC (Library of Congress) and NYPL (New York Public Library). It does follow, however, the current practice of French writers in rendering the name as the French National Library and the new building as the François Mitterand/Tolbiac Library.

Appendix 1: François Mitterand/Tolbiac Library

| Some Statistics | |

Note: Many of the figures below are approximate. Even in the BNF’s own publications they vary, especially on number of items in the collections. Most figures come from the press kit of October 1998, supplemented in some cases by the BNF’s two handbooks for readers (issued at about the same time). | |

Ground area | 7.5 hectares |

Building | |

Upper Garden Level | 26,540 sq. mts. |

Lower Garden Level | 28,680 sq. mts. |

Towers | |

Height | 78 mts. |

Number of floors per tower | 20 (7 offices, 11 of stack, 2 of mechanical equipment) |

Office surface | 16,240 sq. mts. |

Stack surface | 26,660 sq. mts. |

Mechanical | 4,000 sq. mts. |

Number of reading rooms | |

Upper Garden Level | 10 (seating 1,645) |

Lower Garden Level | 14 (seating 1,700) |

Costs | |

Site: none (given by city of Paris) | |

Building, furniture, equipment and other costs: 8,000,000,000 FF | |

(about $1,200,000,000 at contemporary conversion rate) | |

Personnel | |

Professional, technical, maintenance | 2,100 |

Collections | |

Printed books | 10,000,000 in stacks 400,000 on open shelves (to increase to 800,000) |

Journals | 350,000 titles (no precise equivalent in volumes, but probably several million) |

Microforms | 1,035,000 titles |

Digital texts | 100,000 works |

Digitized images | 300,000 items |

Sound and video recording | 1,000,000 items |

Collections at the Richelieu site They include the five specialized collections not transferred to Tolbiac. (A sixth, Performing Arts, will move from the Arsenal Library to the Richelieu complex.) | |

| Coins, Medals, Antiquities | 390,000 coins 110,000 medals 300,000 other items |

| Manuscripts | 120,000 volumes of western manuscripts 220,000 volumes of Oriental manuscripts |

| Maps and Plans | 675,000 maps 786,000 volumes and pamphlets 135,000 photographs |

| Music | 2,000,000 items (sheet music, autographs of musicians, press clippings, opera librettos, etc.) |

| Prints and Photographs | 12,000,000 items (prints, photographs, architectural plans, post cards, playing cards, etc.) |

Collections at the Arsenal | |

| Arsenal Library | 1,000,000 printed books 11,400 journal titles (no precise equivalent in volumes) 120,000 other items (manuscripts, music, etc.) |

| Performing Arts | 2,400,000 items (books, periodicals, programs, theatre prints and photographs, designs for sets, clippings, etc.) |

Appendix 2: Bibliothèque Nationale de France

| Key Historical Dates | |

| 15th Century | Royal library of Louis XI (1461‐1483) |

| 1537 | Ordonnance de Montpellier (legal deposit) under François I |

| 1789‐1800 | Royal Library (Bibliothèque de roi) becomes Bibliothèque Nationale; growth of collections from confiscated libraries of nobility and clergy |

| 1859‐1873 | Construction of BN’s main reading room and stack under plans of Labrouste |

| 1874‐1905 | Administration of Lèopold Delisle |

| 1897‐1981 | Publication of the Catalogue général des livres imprimés (231 v.) |

| 1930‐1964 | Administration of Julien Cain |

| 1983 | Closing of card catalog |

| 1980s | Discussion of library’s space needs; proposal for “Bibliothèque Nationale bis” by E. Le Roy Ladurie |

| 1988, July 14 | François Mitterand announces plan for a new library (une très grande bibliothèque, dubbed TGB by press) |

| 1989 | Selection of Dominique Perrault as architect for the Bibliothèque de France (EPBF) |

| 1992‐1993 | Site preparation; construction begins |

| 1993, Fall | Much of basic structure in advanced stages of construction |

| 1993 | Bibliothèque Nationale and Bibliothèque de France merged (effective Jan. 1994) to form Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF), to operate on two main sites (Richelieu and Tolbiac) |

| 1995, March | Completion of François Mitterand/Tolbiac Library |

| 1996, Dec. 16 | Opening of public service at Tolbiac building (upper level for general public); Plaque indicates the role of François Mitterand |

| 1997 | Transition work (e.g., completion of the information system, transfer of personnel, planning for future use of and renovation of Richelieu building) |

| 1998, March | Moving of printed book collection (ca. 10,000,000 volumes) from Richelieu to Tolbiac (continues to end of 1998) |

| 1998, Aug. | Services at Richelieu closed for one month |

| 1998, Oct. 9 | Opening of research collection public services (lower level) at Tolbiac building |

Appendix 3: For Further Reading in English

The catalogs of most large American research libraries contain many entries (albeit under several variant forms) for publications by and about the BNF. Most of them are, however, catalogs of exhibitions held at the library over the years or—in the case of the past decade—about the new building at the Tolbiac site on the Left Bank. Relatively little is available in English; the 11 items listed below were selected as most helpful to the student or scholar without a reading knowledge of French. Brief annotations highlight each one’s coverage and possible use. The BNF’s web site provides some additional information (see below).

| Bibliothèque de France. |

| 1992, Year of the Foundation [Paris, Bibliothèque de France, 1992] 64 p. |

| A well illustrated booklet, issued as construction of the François Mitterand/Tolbiac building was about to begin. Covers both the building and operational plans for the Bibliothèque de France, as originally conceived and somewhat modified following extensive public debate and comment from 1989 to 1991. Now chiefly useful as a report on the “work in progress” and to show how the original plans and lines of development have changes but slightly in later years. |

| Bibliothèque Nationale. |

| The Bibliothèque Nationale. [Paris, Publications Nuit et Jour, c1993] (Beaux Arts, special issue) 73 p. |

| A kind of introduction to the Bibliothèque Nationale as it was at the Richelieu site in the early 1990s, under four headings: buildings, collections, “the secret library” (i.e., technical processes and related operations), and “the future” (brief mention of the new building at Tolbiac and the plan, later discarded, to create a National Art Library at the Richelieu site). Major portion of book (pp. 20‐59) consists of full color illustrations of examples of holdings (e.g., books, maps, manuscripts). |

| Bibliothèque Nationale de France. |

| Bibliothèque Nationale de France. [English ed. Paris, Connaissance des Arts, c1997] 70 p. |

| A general introduction to the BNF’s history, special collections, services and cultural policy. Sections on the François Mitterand/Tolbiac building and its operations presented in the form of question‐and‐answer interviews with Dominique Perrault and Jacqueline Sanson. Contains 75 illustrations, most in full color. |

| Bibliothèque Nationale de France. |

| Le site Tolbiac, 1994 [Bilingual ed. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, c1994] 24 p. |

| A bilingual publication with brief general information on the building at Tolbiac. About half the pamphlet consists of color illustrations of construction then in progress; also includes floor plans for the library’s upper and lower levels, as well as discussion of operations following the 1996 opening. |

| Bibliothèque Nationale de France. |

| XXIe, into the Twenty‐First Century. [1998 ed. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1998] 70 p. |

| Most recent and probably best account for professionals interested in the BNF as it now operates at its two main sites (Richelieu and Tolbiac). Introduction by Jean Pierre Angremy, the institution’s new president. Presents information under four headings: (1) “a national heritage library,” (2) “into the twenty‐first century,” (3) “a journey through time: exploring the BNF collections,” and (4) “behind the scenes.” Fewer illustrations that the Connaissance des Arts and Beaux Arts books cited above. List of major officials. Considerable portions of text incorporated into BNF web site (see below) |

| Blasselle, Bruno. |

| “Bibliothèque Nationale.” In: World Encyclopedia of Library and Information Services. 3rd ed. Chicago, American Library Association, 1993, pp. 124‐127. |

| An excellent, concise article on the history, organization, collections, etc. of the “old BN” as of the early 1990s, with only brief mention of the then‐separate Bibliothèque de France. |

| Bloch, R. Howard, and Hesse, Carla, eds. |

| Future Libraries. Berkeley, University of California Press [c1995] (Representation Books, 7) 159 p. |

| Volume growing out of a conference on “The Très Grande Bibliothèque and the Future of Libraries,” held at the University of California, Berkeley. Only four of the 10 papers included deal specifically with the “old BN” and the Bibliothèque de France (not yet merged to form the BNF): “History, Philosophy, and Ambitions of the Bibliothèque de France,” by Dominique Jamet and Hélène Waysbord; “New Orders of Knowledge, New Technologies of Reading,” by Gerald Grunberg and Alain Giffard; “My Everydays,” by Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie; and “Books in Space: Tradition and Transparency in the Bibliothèque de France,” by Anthony Vidler. No index. |

| Esdaile, Arundell. |

| “Paris: La Bibliothèque Nationale.” In: his National Libraries of the World: Their History, Administration, and Public Services. 2nd ed., completely rev. by F. J. Hill, London, The Library Association, 1957, pp. 49‐76. |

| Excellent historical account of the “old BN” from its earliest days to the 1950s. Covers buildings, catalogs, organization, staff, etc. Very useful for understanding what the BN was like shortly after World War II ended. |

| Favier, Jean. |

| “The History of the French National Library.” In: Books, Bricks, and Bytes. Cambridge, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1996. (Daedalus, volume 125, number 4, pp. 283‐291, Fall 1996). |

| Not a chronological summary of the library’s history, but rather an overview of and reflection on the BNF in light of its long history and heritage. Written before the opening of the building at the Tolbiac site by the BNF’s first president, the article also touches on the challenges faced by the “new” institution. |

| Jackson, William V. |

| “Bibliographic Tools and Techniques for the Study of Latin American Resources at the Bibliothèque Nationale.” In: Gleaves, E.S. and Tucker, M.J., eds. Reference Services and Library Education: Essays in Honor of Frances Neel Cheney. Lexington, MA, D. C. Heath [1982], pp. 131‐146. |

| Discussed the techniques used in the early 1980s to report on the nature and extent of the Latin American holdings at the Richelieu site. Explains the problems in having to use many catalogues (including 4 by authors and 5 by subjects) to study resources in the period immediately preceding the library’s projects to automate bibliographic records. |

| Tesnière, Marie‐Hélène, and Prosser, Gifford, eds. |

| Creating French Culture: Treasures from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. New Haven, Yale University Press, in association with the Library of Congress, Washington, and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris [c1995] 480 p. |

| A lavishly illustrated catalog of 207 treasures from the Middle Ages to the 20th century exhibited at the Library of Congress. Arranged chronologically in 4 parts: (1) “Monarchs and Monasteries: The Early Years,” (2) “From Royal Collections to National Patrimony,” (3) “The Kings Collect for the Savants,” and (4) “Revolution, Empire, and the Independence of Culture.” Each part preceded by two signed essays, which, taken together, give historical perspective. Also contains an introduction by Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie and a 12‐page chronology of France’s political and cultural history. Detailed index. Text and images also available at Library of Congress web site (http://lcweb.loc.gov/exhibits/bnf) |

The BNF Website

There is an extensive website for the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, with most, but not all, sections available in English as well as French; the opening page points out that “The new English version is under development.”

- The main sections of the English version are as follows:

- Historical overview

- What is the BnF?

- The new library at Tolbiac

- Exploring the BnF collections

- The BnF and the libraries network

- What’s on? Cultural news and information on the BnF

- Practical information

- BnF bibliography [21 items, all in French]

The web site is http://www.bnf.fr/institution/anglais **. A print out of these sections in English runs to more than 90 pages.

The exhibition at the Library of Congress, “Creating French Culture,” can be located under the LC home page (see last item above). In addition, the BnF has also mounted on the web (text and images) “The Age of Charles V (1338‐1380): 1,000 illuminations from the Department of Manuscripts” (http://www.bnf.fr.enluminures)

** Editor’s note: The current English language version of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France website, as of 19 October, 2012, is http://www.bnf.fr/en/tools/lsp.site_map.html. There is no current analogue for the original link to “1,000 illuminations from the Department of Manuscripts” noted above.

A Note On Sources

This report draws on many sources, both published and unpublished. In addition to the works in English listed above, numerous monographs and articles in French were utilized. The press kits distributed at the openings of the François Mitterand/Tolbiac Library (December 1996 and October 1998) supplied some information, as did flyers and handbooks for readers. Over the past two decades the author has regularly done research at the BNF and has interviewed a number of staff, including Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie and Dominique Jamet, directors respectively of the Bibliothèque Nationale (BN) and the Bibliothèque de France (EPBF) when they were merged to form the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF).

About the author

William Vernon Jackson, Professor Emeritus at the University of Texas in Austin, is currently Senior Fellow at Dominican University. He received the B.A. “With Highest Distinction” from Northwestern University, Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literature from Harvard University, and M.S. (in L.S.) from the University of Illinois. He has held teaching positions at Illinois, Wisconsin, Pittsburgh, Vanderbilt, as well as Texas

He has long specialized in library development in Latin America, as well as on Latin American resources in U.S. institutions, and has undertaken numerous assignments in all parts of the region. He has been visiting professor at the library schools of the University of Antioquia and the University of Buenos Aires and has written numerous books, reports, articles, and reviews, including Aspects of Librarianship in Latin America (1962, 2nd ser., 1992).

He was awarded the first Fulbright research grant in library science to France and has done extensive research on the Latin American resources of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The present report is an outgrowth of his ongoing comparative study of the five mega libraries of the western world (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, British Library, Harvard University Library, Library of Congress and New York Public Library.)