Management Prospects and Challenges of Library Associations in Africa: The Case for Uganda Library Association and the Library and Information Association of South Africa

Abstract

For professional library associations to meaningfully contribute to the development of LIS institutions and professionals in Africa, management issues need to take center stage and attention. This paper draws from the experiences of two associations in Africa to describe their approach to management and lessons for other professional bodies. The Uganda Library Association (ULA) realized remarkable achievement through strategic planning and the Library and Information Association of South Africa (LIASA) through the establishment of democratic structures and project management. The author identifies strategic planning, partnership building, and internal democratic structures as key in the success of LIASA and ULA. Strategic plans for the two bodies are discussed with emphasis on implementation strategies. LIASA and ULA provide good cases for other associations in Africa to address their own challenges but more documentation of what has worked, where and how is needed for purposes of sharing experiences.

1.0 Introduction

Library and information associations play a vital role in the development of the Library and Information Science profession and the socio‐economic transformation of communities by ensuring that information institutions render quality information related services. By organizing librarians and information professionals, library associations create a forum for meeting, exchange of views and learning from each other which is important if similar problems and challenges are to be collectively addressed (Russell 1989). Associations are appropriate bodies to regulate the profession through accreditation of education programs and control of information professionals through a professional register and professional code of conduct (Kigongo-Bukenya 2000). Associations encourage members to contribute to research and publication in the field. In Africa, as in other developing areas, associations suffer from such problems as lack of headquarters and permanent addresses where, for instance, to send subscriptions (Watts‐Russell 1988). Lack of office space and permanent staff, insufficient funds, poor communication within and outside the association, leadership needs and many other problems continue to challenge the existence of these organizations. Situations like these hinder associations’ effective contribution to the development of the profession and library institutions, seriously undermining participation by members they are perceived as having nothing or little to offer.

Whereas it is difficult to point to a single problem, management knowledge and experience to produce and implement a viable program for the professional needs of the continent has largely remained a major deficiency in most of these organizations. Russell (1989) observes that few organizations are able to provide a unified voice, agree upon objectives, identify strategies to achieve them and embark on activities to fulfill these targets, characteristic of association in developing countries. Contrary to the above situation, associations in the developed world are more likely to have clear management plans that connect with their missions. For instance, the Association of Library and Information Science Education (ALISE) in its 2000‐2002 Strategic Plan resolved that, “the activities of ALISE should address critical societal issues related to its mission and should evolve from a strategic planning process.” Due to lack of permanent staff, association leadership in Africa is usually charged with the day‐to‐day functions of the organization and because they are fulltime employees elsewhere, overall performance is lowered. Depending on the individuals nominated to leadership positions, this is an opportunity to get talented, hardworking members to serve the association membership (Erazo 2000). Their management skills and ability to evolve a plan of action determines how much is accomplished in their term of office. Even when leaders have the skills, the fact that they relinquish office on expiration of their term causes lack of continuity in the program implementation.

IFLA’s Roundtable on Management of Library Associations (RTMLA) was set up in 1983 in an effort to address management challenges faced by library associations, especially in developing countries (IFLA 2001). According to Russell (1989) the objectives of the round table at its inception were:

- To assist library associations to more effectively contribute to the formulation and execution of IFLA policies and activities;

- To monitor and collect information on the structures, management, organization and activities of library associations;

- To assist library associations to implement UNESCO NATIS/UNISIST programs and IFLA's UBC Program and UAP;

- To offer advice and assistance from the expertise within the Round Table to library Associations in membership;

- To collect specialist information for exchange among associations (Russell 1989).

The Roundtable set out to accomplish its programs through production of management guidelines for library associations; identification of a “model” library association in the different IFLA regions, and organization of regional seminars based on the “model” associations. Other goals were to establish an IFLA clearing house, preferably located in IFLA headquarters, to collect information on library associations; assist in the development of income‐generating services in library associations; prepare an investigation into the state‐of‐the‐art on trans‐border data flow; publish “The role of library associations as effective pressure groups for ‘political’ action;” assist associations to encourage “professionalization” of their memberships; encouraging UNESCO to understand and provide support for library association development; and assemble a program of activities to assist library associations (Russell 1989).

The International Network for the Availability of Scientific Publications (INASP), in collaboration with the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Danish International Aid (DANIDA), is currently involved in rededication and/or resurrection of regional and national library associations in Africa. INASP support targets enhancing capacity of the professional organizations in the region to effectively play their roles in professional and regional development (INASP 2002). Priority areas include: support to conferences, research activities, newsletter and inter‐regional cooperation. Bodies that have received support include: the Standing Conference for Eastern, Central and Southern African Librarians (SCECSAL), the Standing Conference of African University Librarians Western Area (SCAULWA), West African Library Association (WALA) and Standing Conference of African National and University Libraries in Eastern Central and Southern Africa (SCANUL‐ECS). INASP supports attendance of librarians to meetings of the Association of African Universities Ad Hoc Committee on University Libraries.

Whereas RTMLA, INASP and other players have registered positive results in their campaign for vibrant professional organizations in the region, most associations in Africa, especially at national level, are yet to feel the impact of their work. A few professional bodies have made some efforts in tackling management‐related problems and challenges by evolving working plans and successfully implemented them. Here I discuss Uganda Library Association (ULA) and the Library and Information Association of South Africa (LIASA) with the aim of understanding management prospects, problems and challenges they have encountered, which provides opportunities for other associations faced with similar challenges or problems to learn and improve their operations.

2.0 Uganda Library Association (ULA)

Uganda Library Association (ULA) came into existence in 1972 following dissolution of the East African Library Association (EALA) in 1970. The old association had covered Uganda, Kenya, Tanganyika, and Zanzibar. EALA broke up mainly due to the geographical barriers that hindered effective participation of professional members in the region, rendering national bodies more viable options. ULA has weathered political, social, economic, and technological changes for the last thirty years of its existence.

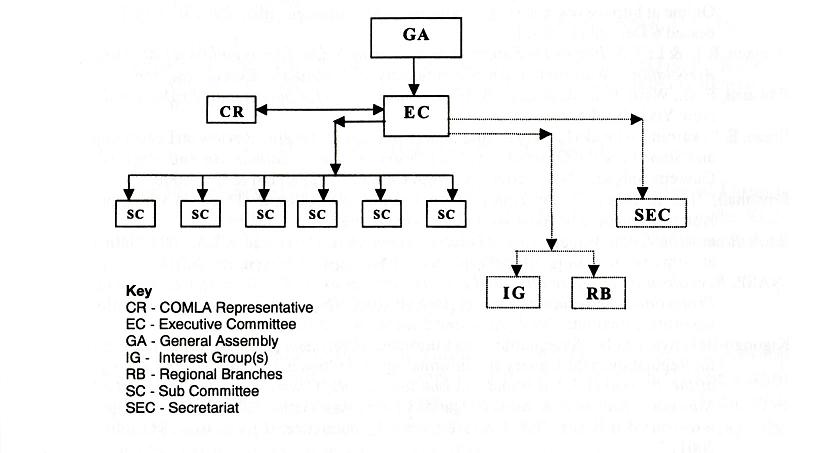

Like most professional bodies, ULA drafted and passed a constitution that provides for establishment of the Annual General Meeting (AGM), Executive Committee (EC) and Secretariat. The constitution empowers the EC to form subcommittees, special interest groups and district branches. The AGM adopts policies initiated by the EC that are supposedly to be implemented by the Secretariat. The AGM is the supreme body in the ULA organization structure (see appendix 1). The organizational structure of the association is a simple one with some organs that have remained non‐existent for the entire lifetime of the Association (shown in dotted lines). All activities of the association revolve around the EC, meaning that effective functioning of the association is primarily a responsibility of this committee. The Constitution requires that EC members be elected into office for a term of two years and are eligible for re‐election for one term. The Association has had volunteers serving on the EC and each of the groups in office adopted a different management approach of its affairs. After evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of past committees, the 1999/2001 group decided to come up with ULA’s first ever plan of action upon which its performance would be measured.

2.1 ULA 2000–2001 Strategic Plan

In 1999, the ULA EC in consultation with the membership came up with a two year Strategic Plan that aimed at integrating libraries and information centers into the daily lives of Ugandans. The Strategic Plan was a “statement of purpose and dedication to influence and build a Ugandan society that values information as stimulus to development” (ULA 1999). The Plan would enable establishment of a framework within which tactical decisions were to be made in a changing environment (Ernstthall & Jones 1996). The plan sought to achieve the following objectives:

- To establish and maintain a Secretariat for ULA.

- To initiate and promote a culture of income generation for Library and Information Institutions.

- To lay strategies for nationwide membership drives and campaigns.

- To promote and offer opportunities for professional development of Library and Information Science practitioners.

- To promote access of Information to members of ULA and the general public.

- To promote and influence positive legislation and policy formulation in the field of Library and Information Science.

- To design and implement community outreach activities.

- To cooperate and network with both Local and International bodies with an interest in any of the activities of ULA (ULA 2000).

The plan was drawn up and discussed by the EC, unveiled to its members for contributions and then launched by Uganda’s Minister of Information in the President’s Office, specifically invited to solicit political support and government’s goodwill towards implementation of the program. Uganda is one of the countries where the government supports civil society initiatives and recognizes them as partners in development. Russell (1989) notes that in such countries where associations are perceived as responsible bodies and are consulted before governmental decisions are reached, the association and government enjoy a good working relationship. It was, therefore, in ULA’s interest to draw the attention of policy makers to the two-year program and the direction the Association intended to take.

Membership participation in association activities was at its lowest at the time, a factor that limited consultation and drafting of the program. However, efforts were made to address as many needs and concerns as possible, both short term and long term. Sources of funding were identified, though by the time of launching the program, none of these sources had made a commitment to support the program. The program priority areas were: establishment of a secretariat, mobilization of resources, increase membership, capacity building, information and publicity, legislation and policy, community outreach, and coordination and collaboration. For each of these areas, activities that require minimum resource input were identified and allotted higher priority and resources.

2.1.1 Program Implementation

ULA has no paid full time staff to monitor day‐to‐day activities of the association. For a sitting executive, the association chairperson has always housed the “secretariat” at his/her place of work. Therefore program implementation was fully the responsibility of the EC, which is not unusual, for Ernstthall and Jones (1996) note that a small group of people should spearhead the organization through the strategic planning process and get intimately involved in development of the framework for the overall process. To avoid burnout by the EC, the following subcommittees were established to focus on specific activities of the program priority areas. The committees included:

- □ Education, Training and Research;

- □ Legislative and Policy Issues;

- □ Community Outreach;

- □ Publicity and International Relations; and

- □ Editorial and Publication.

Members were invited to serve on committee of interest by applying to the EC and applications received were reviewed and selections made bearing in mind the member’s expertise and the committee’s scope of work. A member of the EC was posted to each subcommittee to ensure that the committee remained focused on the strategic program and moving in the right direction. This way, a strong link was created between the EC and the committees, which facilitated articulation of the vision of the program to the subcommittee. In the course of the program implementation, this person would periodically report back to the EC on progress of the subcommittee during the EC’s evaluation meetings. Because a considerable part of the activities were spread among committees, the EC was in a position to take up the work of any committee that failed to undertake its activities in the absence of a substantive secretariat with full time staff.

2.1.2 Collaboration for Program Implementation

Professional organizations, particularly in developing countries, usually operate on a small resource base in addition to the lack of basic facilities for running association activities. However, there are organizations that share interests with library association with problems and challenges that are not necessarily similar to those faced by library bodies, making it logical that library associations identify and forge partnership with such organizations. Collaborative efforts like these are relevant to professional bodies both in the developing and the developed world. Commenting on the Canadian Library Association’s 1998‐2000 Strategic Plan, Sydney (1999) noted that, “it has become evident that CLA doesn’t have the resources...out there are opportunities to forge mutually beneficial alliances with other groups, associations and individuals.”

ULA identified and sought ties with the following organizations with activities inclined towards the Association’s strategic program. The Association collaborated with the following organizations:

- National Book Trust of Uganda (NABOTU)

NABOTU is a civil society organization that acts as an umbrella organization for all stakeholders in the book industry in Uganda. NABOTU’s mission is “to promote a reading culture as well as development of a sustainable book industry in Uganda”, (UPA 2001, 8). NABOTU’s interest in literacy issues made it a strategic partner with which ULA could work to achieve most of the literacy points of the strategic plan. Through NABOTU, ULA was afforded the opportunity to forge links with organizations like Uganda Publishers’ Association, Uganda Book Sellers’ Association, Reading Association of Uganda, Public Libraries Board, Uganda Women’s Network and Kampala Children’s Library, all members of NABOTU.

The coordination of literacy activities was made possible under the framework eliminating unnecessary duplication and allowing for optimal utilization of meager resources available to participating organizations. With support from The Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) through NABOTU, ULA was able to organize reading tents, a literacy project targeting children aimed at inculcating the reading culture at an early age.

- The East African School of Library and Information Science (EASLIS)

EASLIS at Makerere University in Kampala is one of the oldest and leading LIS training institutions in East and Central Africa. Established in 1963, the school was created to meet library training needs in the region following the independence of the three East African Countries of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. EASLIS has since then graduated a sizable number of librarians serving not only in Uganda but also in other countries in Africa and around the world. EASLIS has had considerable influence on activities of ULA, being the main source of its membership.

The school administration extended office space to ULA to serve as a temporary “secretariat” and assist in coordination of association activities. ULA also makes use of the school’s facilities to organize professional workshops and seminars where faculty members help facilitate. Other units at Makerere with which ULA collaborates are the Institute of Computer Science and Makerere University Library Services by extended resource persons and facilities for training.

- The School of Library and Information Studies (SLIS), University of Oklahoma

The SLIS at Oklahoma University offered server space to host ULA’s “website” enabling the association to have a global reach on the web [Available at: <http://www.ou.edu/cas/slis/ULA/ula_index.htm>]. As long as the costs of Internet access and hosting in Africa remain unaffordable by library associations, this approach is the sure way of getting web presence, vital in today's digital society.

- Other Collaborators

For a civil society organization ULA is, there was a need to work with governmental departments and ministries like the education ministry and that of information. These were strategic in regard to policy issues especially the School Library and the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) policies. The School Library Policy, though not yet passed, is one issue in the area of advocacy where ULA has made progress with the Education Ministry. Working through the legislation and policy issues subcommittee, ULA drafted guidelines to the ministry for consideration in streamlining the running of libraries in primary and secondary schools. Relevant authorities in the ministry cooperated by inviting ULA to consultative meetings and subsequently agreed to consider the proposed guidelines. Collaboration with the education ministry extended to receiving books for use in organizing the children’s reading tent project and other outreach activities of the Association. Regard the ICT Policy document, ULA worked with the ICT Task Force of the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCS&T) by actively making contributions towards the draft policy document representing opinions of ULA membership.

Companies dealing in library-related materials are partners associations need to work with. In the case of ULA, several of these were invited to exhibit their products at ULA meetings in return extending financial and moral support to the association in form of donations and advertisements in ULA publications. Funds realized were directed towards different program activities especially production of publications. Companies contacted included publishers, booksellers, hardware and software dealers, among others.

Collaboration and partnership building can partly address the problem of inadequate resources faced by library associations in Africa. ULA’s experience is evidence of such possibilities and provides an array of partners with whom library associations may work in individual African countries.

3.0 The Library and Information Association of South Africa (LIASA)

The Library and Information Association of South Africa was formed in 1997 following unification of all library and information organizations in South Africa. The unification process was initiated in 1995 by the two largest organizations at the time, the Africa Library Association of South Africa (ALASA) and South African Institute for Librarianship and Information Science (SAILIS). An Interim Executive Committee was put in place in 1996 with a mandate to draft a constitution, which was discussed and passed in 1997.

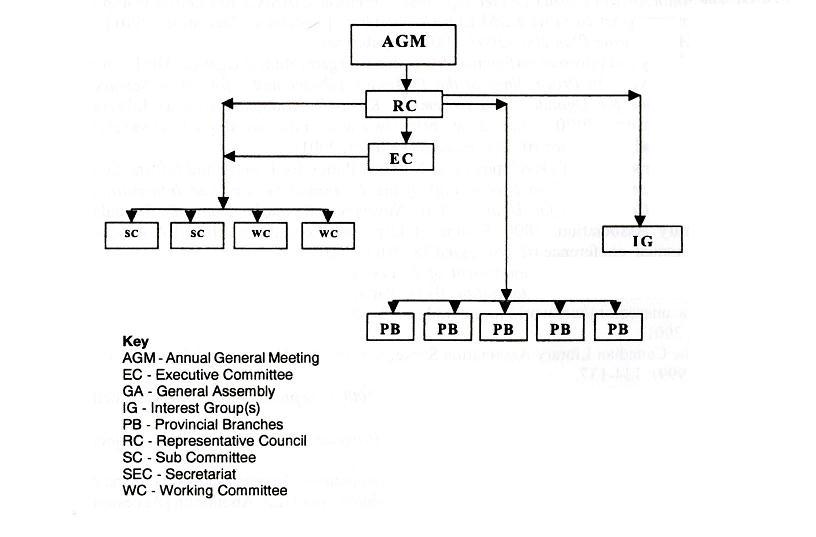

LIASA is another professional body in Africa whose visionary leadership successfully handled the merger and subsequently established one of the most vibrant professional bodies on the continent. LIASA’s success can be attributed to, among other things, creation of democratic structures through a well‐drafted constitution that provides for establishment of the Annual General Meeting (AGM), Representative Council (RC), the Executive Committee of the RC, Provincial Branches (PB) and Interest Groups (IG). AGM is the overall policymaking body. The RC implements the policies adopted by the AGM.

On the Association management, the constitution points out that “management of the Association is vested in the membership which acts as ... the authority at the Annual General Meeting. The AGM mandates the Representative Council as its highest organ to act on behalf of the Association ... and pass resolutions with the powers granted to it” (LIASA 1997). RC is charged with:

- Dealing with national matters affecting LIS and LIS workers, and to represent the Association nationally and internationally;

- Executing policy made by the AGM;

- Controlling and co‐ordinating the finances of the Association and submit duly audited financial statements to the AGM following the end of the financial year to which the statements apply;

- Keeping records of members;

- Consulting with branches and interest groups on matters affecting LIS and LIS workers;

- Organizing the AGM, and report on its activities to the AGM;

- Coordinating and facilitating the formation and functioning of branches and interest groups;

- Planning strategically for the Association;

- Promoting achievement of the aims of the Association in consultation with branches and interest groups;

- Consulting experts where necessary and inviting persons from time to time to attend RC meetings in observer capacities, though it may not co‐opt persons onto the RC (LIASA 1997).

The constitution also established the Executive Committee (EC) of the RC, “to execute the day‐to‐day activities of the Association as mandated by the Representative Council” (LIASA 1997). EC reports to the RC and EC’s membership is in such a way that the President, Deputy President, Secretary and Treasurer of the RC also serve on the EC. LIASA Executive Director, who heads the National Office (Secretariat), is a member of both the RC and EC. The linkage between RC, EC and National Office has ensured efficient functioning of the three bodies and overall performance of the Association’s leadership.

Three years following its unification, LIASA adopted a corporate plan for the period 2001‐2003 with 7 key business areas of focus:

- Strategic and business planning;

- Membership recruitment and management;

- Communication, marketing and public relations;

- Continuing training and development;

- Advocacy;

- Extending collaborative partnerships; and

- National office: management services and financial management (LIASA 2001)

The plan quickly attracted attention of development partners like the Carnegie Corporation of New York whose grant facilitated establishment of the LIASA National Office to serve as a secretariat, a major step considering that several associations have no functional secretariats. Staff at the secretariat include the Executive Director, Professional Officer and Administrative Assistant whose “key performance areas” include strategic and business planning; membership recruitment and management; communication, marketing and public relations; continuing training and development, advocacy and extending collaborative partnerships; and, overseeing the National Office and finances (Tise, E. 2001). Establishment of a National Office enabled the RC and EC to focus their energies on issues of a strategic nature, like policy formulation. The Office plays an important role in identifying funding opportunities and sources of income, in addition to membership subscriptions, which according to Russell (1989) is one of the key priorities of staff employed by an association. LIASA’s membership has increased steadily to the present figure estimated at 1983, and there are indications that it will continue to increase.

LIASA adopted the project approach to implement its corporate plan with specific projects developed to address specific business areas of the plan. A leadership skills development project addressing the continuing training and development area of the plan is of interest and discussed below. This project will eventually develop a pool of professionals with sufficient management skills to benefit not only information institutions in South Africa but also LIASA as professional body.

3.1 The South African Library Leadership Project (SALLP)

Projects identified and implemented within broader strategic programs, are likely to provide exciting opportunities for better management and functioning of LIS bodies in Africa. LIASA set up a number of projects, but the South African Library Leadership Project (SALLP) deserves special attention due to its potential of developing a critical mass of leaders for South African academic, public and national library services.

SALLP is aimed at developing leadership qualities in current and future managers of academic, public, community, and national library services. The project, established in December 2000 with a grant of $250,000 from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to the University of Illinois at Urbana‐Champaign, is to train 18 library professionals over a period of three years. The project will benefit LIASA in two ways: selected participants get involved in LIASA annual conferences and committee activities and a pool of librarians with leadership and managerial skills will be developed which strengthens the professional body and individual library institutions (LIASA 2000). Where as a number of professional bodies in Africa may have the capacity to mobilize local resources for association activities, there is a significant lack of personnel with sound management skills, leading to poor performance of the associations in regard to core activities. A full time coordinator was appointed to oversee day‐to‐day activities of the SALLP project, a position not common in the organizational structures of most LIS professional bodies in Africa. Mobilization of resources for the project calls for skills in proposal writing, which LIASA addressed through workshops on “Grant Proposal Writing” with support of the Carnegie Corporation of New York under the Revitalization of Public Libraries Programme. The workshops were presented to LIASA members in different provincial branches of the Association. The project provides insights on how associations in Africa might want to address shortage of managerial and leadership skills within their ranks.

4.0 Challenges for LIASA and ULA

ULA and LIASA need to integrate an elaborate program evaluation component they adhered to in the program implementation as a way of generating information to better design future programs and projects. In order to effectively incorporate a learning mechanism, the following set of questions provides good criteria for developing program evaluation activities:

- Do plans draw upon institutional data?

- In what ways do strategic...plans include learning goals and priorities?

- What on‐going data collection (qualitative and quantitative) and analysis are used to assess effectiveness of planning?

- How does the planning process include assessment of learning?

- How is evidence of outcomes and effectiveness used in planning [for future programs]?

- To what extent is learning an integral and embedded part of planning discussions? (Edwards, et al, 244).

Business focus area 7 of LIASA’s Corporate Plan (LIASA 2001) on “National Office Management Services and Financial Management” makes a brief reference to “annual review” of its corporate planning process but does not outline detailed procedures or mechanisms of how the reviews are to be carried out and how information generated will be incorporated into future programs. ULA’s plan completely lacked provision for evaluation apart from a brief mention of regular executive meetings.

For associations with no programs, most challenges arise from failure to prioritize in resource allocation, leading to attempts to accomplish too much with meager resources, usually resulting in little or no output at all. If association projects and activities are not carried out in the context of broad and coherent strategic programs, deciding on competing priorities and best use of limited resources is usually unattainable (Moore 2000). Ernstthall and Jones, 1996 observe that, “the problem common to many associations is the desire to be all things to all categories and sub‐categories of members. Every idea or project has its champion, and the organization may be reluctant to say no or to set priorities. As a result, many projects and programs are undertaken without sufficient staffing or financing because resources are spread too thin.” (Ernstthall and Jones 1996). LIASA and ULA have taken steps to address this with positive outcomes; other associations in Africa with no such programs ought to move in the same direction. Sustainability of projects and association activities, some donor funded, may affect the two bodies should such funding cease; hence the need for alternative sustainable sources of funding. ULA had an idea of offering consultancy services as a strategy to generate income, which never took off due to lack of personnel committed to its set‐up and LIS professionals oriented towards information consultancy as a career option. The economic instability threatens achievements gained by the two associations and prospects for sustainable implementation of projects that are critical to effective participation of associations in LIS activities at national and international levels.

5.0 The Way Forward for Associations in Africa

ULA and LIASA present exciting opportunities and examples of good association management practice. This is not to suggest that other associations in Africa are not making efforts towards addressing management and leadership related challenges and problems. The paper was intended to dwell on those aspects of association leadership that have worked for ULA and LIASA, other associations may consider to argument their management approaches.

5.1 Communication for Effective Management

Communication is critical for effective leadership and overall association management manifested through an enthusiastic membership actively involved in professional issues sponsored by the association. Communications bridges the gap between the association leaders and its membership. A regular newsletter or journal represents the cement that holds together the bricks of the association membership (Russell 1989). Associations in Africa need to embrace and make use of emerging information and communication technologies like electronic mail, electronic discussion lists and websites. These can go a long way in supplementing traditional communication tools and media like newsletters, brochures, fliers, meetings, and conferences. Both ULA and LIASA recognize information as a vital resource for proper running of the associations. The two maintain newsletters and websites for communication purposes. LIASA also created an electronic discussion list, overcoming geographical and physical barriers in the vast South African state. There is no doubt, however, that circumstances will always vary from country to country, calling for innovation in communication strategies.

5.2 Government’s Role

Associations in Africa have to lobby their governments to establish a statutory body linking the government and the professional body to enhance good working relations between the two. Magara (2000) proposed the National Governing Council (NGC) for Uganda, a governmental body which would administer the professional code of ethics, register and issue certificates to practitioners, set accreditation procedures of training programs, and bring together stakeholders in the book sector in Uganda. Whereas NGC is a good proposal, ULA is better positioned to perform some of these duties itself, in which case NGC ought to recognize and work closely with the professional body. The National Council for Library and Information Services (NCLIS) of South Africa is comparable to Magara’s proposed NGC. With the NCLIS in place, association leadership is in better position to work with the government on matters like standardization, regulation of the profession through a code of ethics, and a professional register among other issues. Generally the body provides the legal and institutional framework within which the leadership can work, allowing them the authority to speak on behalf of the profession and the association. The approach strengthens associations and is an indicator of governments’ commitment to supporting the information sector and library development specifically. Associations in Africa have to lobby their governments to establish a statutory body linking the government and the professional body to enhance good working relations between the two. Magara (2000) proposed the National Governing Council (NGC) for Uganda, a governmental body which would administer the professional code of ethics, register and issue certificates to practitioners, set accreditation procedures of training programs, and bring together stakeholders in the book sector in Uganda. Whereas NGC is a good proposal, ULA is better positioned to perform some of these duties itself, in which case NGC ought to recognize and work closely with the professional body. The National Council for Library and Information Services (NCLIS) of South Africa is comparable to Magara's proposed NGC. With the NCLIS in place, association leadership is in better position to work with the government on matters like standardization, regulation of the profession through a code of ethics, and a professional register among other issues. Generally the body provides the legal and institutional framework within which the leadership can work, allowing them the authority to speak on behalf of the profession and the association. The approach strengthens associations and is an indicator of governments’ commitment to supporting the information sector and library development specifically.

6.0 Conclusion

LIASA and ULA show a beacon of hope for better management and prosperity of professional library associations in Africa. Remarkable successes realized in the areas of: strategic planning and project implementation, democratization and institutional building, partnership and collaboration, and communication. These are issues other associations in Africa might consider to better manage their own associations. They also ought to consider sharing experiences on what has worked where and why through documentation.

However, ULA and LIASA seriously need to consider sustainability of projects and/or programs; mobilization and maintenance of membership, and elaborate evaluation mechanisms fully integrated into the programs from which to draw lessons for present and future programs.

Consultancy services and volunteer management could be workable options. Blanken and Liff (1999) suggest that volunteer management, where leaders are only committed to a short term in office, results in greater volunteer participation and overall membership growth of the association. Involvement by members should lead to greater identification with the associations, which is a workable approach for tapping skilled members into leadership positions. Overall, ULA and LIASA are indeed a beacon of hope for associations and librarianship in Africa.

Appendix 1: UGANDA LIBRARY ASSOCIATION‐ ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE

|

Appendix 2: LIBRARY AND INFORMATION ASSOCIATION OF SOUTH AFRICA

|

References

a) ALISE Time Frame for Goals and Objectives: 2000/2001‐2001/2002. Reston, ALISE. (2000) Online at: http://www.ahse.org/nondiscuss/assoc_strategic_plan_2000‐02.html [Accessed 6 December, 2001].

b) Blanken, R.L. & Liff, A. Facing the Future: A Report on the Major Trends and Issues Affecting Associations. Washington: American Society of Association Executives, 1999.

c) Edwards, E. G., Ward, P. L., & Rugaas, B. Management Basics for Information Professionals. New York: Neal‐Schuman, 2000.

d) Erazo, E. “Learning to Lead a Library Association: A Selective Literature Review on Leadership and Some Personal Observations.” In Library Services to Latinos: An Anthology, ed. Guerena Salvado, 7‐17. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2000.

e) Ernstthall, H.L. & Jones, B. Principles of Association Management 3rd ed. Washington: American Society of Association Executive, 1996.

f) IFLA. Roundtable for the Management of Library Associations. The Hague, IFLA, 2001. Online at: http://www.ifla.org/VII/rt6/rtmla.htm [Accessed 15 November, 2001]

g) INASP Revitalisation of Information and Library Services to the Public in Africa: Regional Professional Associations Oxford, INASP, 2000. Online at http://www.inasp.info/lsp/professional/intro.html [Accessed 5 December, 2001]

h) Kigongo‐Bukenya, I.M.N.“Safeguarding the Information Professional and the User: The Case for Regulation in the Library and Information Profession in Uganda.” In Proceedings of the 1st Annual Library and Information Science Conference for Uganda, 8‐10 November, Kampala. Kampala: Uganda Library Association, 2000. Online at http://www.ou.edu/cas/slis/ULA/Assets/1st_annual_conference.rtf [Accessed 28 October, 2001]

i) Lor, P.J. LIASA: The Birth and Development of South Africa’s New Library Association. [Internet] The Hague: IFLA, 1998. Online at: http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla64/089-97e.htm [Accessed 12 October, 2001]

j) LIASA. LIASA Constitution. Pretoria: LIASA, 1997. Available from: http://home.imaginet.co.za/liasa/constitution.html [Accessed 22 September, 2001]

k) LIASA. The South African Library Leadership Project. Pretoria: LIASA, 2000. Online at http://home.imaginet.co.za/liasa/SALLPbackround.htm [Accessed 5 December, 2001]

l) LIASA. LIASA Corporate Plan 2001‐2003 2001. Unpublished.

m) Magara, E. “Library and Information Science Professional Organization in Uganda: The Future Perspective.” In Proceedings of the 1st Annual Library and Information Science Conference for Uganda, 8‐10 November, Kampala. Kampala: Uganda Library Association, 2000. Online at: http://www.ou.edu/cas/slis/ULA/Assets/lst_annual_conference.rtf [Accessed 28 October, 2001]

n) Moore, N.“A Framework for Development: A National Policy for Library and Information Services in Uganda.” In Proceedings of the 1st Annual Library and Information Science Conference for Uganda, 8‐10 November, Kampala. Kampala: Uganda Library Association, 2000. Online at: http://www.ou.edu/cas/slis/ULA/Assets/lst_annual_conference.rtf [Accessed 28 October, 2001]

o) Russell, B. Guidelines for the Management of Professional Associations in the Fields of Archives, Library and Information Work. Paris: UNESCO, 1989. Online at: http:// www.unesco.org/webworld/ramp/html/r8911e/r8911eOO.htm [Accessed 3 November, 2001]

p) Sydney, J. “The Canadian Library Association Strategic Plan: One Year Later.” Feliciter, 45‐3 (1999): 134‐137.

q) Tise, E. LIASA Annual Report for the Period September 2000 to September 2001. Unpublished Report of the President.

r) Uganda Library Association. A Two Year Strategic Program. 1999. Unpublished Project Document.

s) Uganda Library Association. About Uganda Library Association. Kampala: Uganda Library Association, 2000. Online at: http://www.ou.edu/cas/slis/ULA/About.htm [Accessed 15 November, 2001]

t) UPA. Uganda International Book Fair 2001. Key Players in the Book Industry-NABOTU. Kampala: Uganda Publishers’ Association, 2001.

u) Walter, L.P. (1988) “Strategic Planning and All That Jazz.” Library Journal, 113‐13 (August, 1988): 51‐55.

v) Watts‐Russell, P. “Revitalizing Public Library Services in Africa: An Open Forum Meeting in Ghana.” Oxford: INASP, 2000. Online at: http://www.inasp.org.uk/newslet/feb01.html#4 [Accessed 17 November, 2001].

Author‐Biographical Note

Richard Kawooya is a Doctoral student at the School of Information Science, University of Tennessee. Email: dkawooya@utk.edu. The author served as Editor and Executive Committee Member of Uganda Library Association (1999‐2001), earned the MLIS from Valdosta State University (2001) and is currently working on a PhD in Communications (Information Science) at the University of Tennessee.

Acknowledgement

This paper was accomplished at Valdosta State University as independent study project under guidance and support of Elaine Yontz, Ph.D. The author also wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Thomas Gwenda, (Executive Director LIASA), and Charles Batambuze, (General Secretary‐ULA) who provided information on the activities of the two bodies.