September 11, 2001 and Libraries: Forging a Professional Persona

Abstract

Proposes a model for a Professional Persona in the wake of the attacks of September 11th, 2001.

September 11th, 2001: Terrorism and the Global Portal Coping with a Terrible Beauty

Terrorism, fear and the clouds of war have colored this fall of 2001. The shock of the staggering, senseless, searing violence of the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon have given way in the United States to a numbing insecurity, nourished by reports of known and unknown powdery substances found in the mails and vague, unspecified government warnings of possible new attacks, even as the war in Afghanistan has begun somewhere out there. In a globalized world, the anxiety has not only manifested itself here at home. Powdery substances have been reported in the mail in places as far apart as Bangkok (Thip-osod 2001), Guyana (Ramotar 2001), and several European countries. A German television news website talks of “Angst vor Post mit Pulver” (ZDF Heute Magazin 2001), and in Norway, one newspaper quoted a psychologist’s diagnosis of a “psychological epidemic” that he warned could be intensified by the media focus on reports of white powdery substances closing city halls, schools and post offices. (Letvik 2001). On October 16th, a Belgian reporter claimed: “En Belgique, c’est la psychose: l’anthrax est partout et nulle part.” [In Belgium, it's a psychosis: anthrax is everywhere and nowhere]. (Delepierre 2001).

The psychosis has engendered a search for coping mechanisms, a search for meaning in the midst of the madness.

I HAVE met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had done

Of a mocking tale or a gibe

To please a companion

Around the fire at the club,

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born. (W. B. Yeats, Easter 1916)

Yeats was in the air in September. In the Observer on the Sunday after the event, a special report maintained that “This horror happened in full view and unmediated, and yet it possessed the terrible beauty and shape of art – which is why perhaps it felt unreal.” (Gerrard 2001). A writer in an Irish newspaper agreed that all was changed, but denied that “terrible beauty,” speaking instead of a “globalisation of sorrow and sadness and an awful realisation that this was the work, not of science fiction monsters, but of members of our own human species.” (Feehily 2001). But in so doing, these writers echoed a phenomenon of the aftermath: the global sharing of poetry through email and websites. There is a weblog that documents the poetry and some of the sites, not, according to its author, “so much [as] an attempt to come up with an answer (as to what the response of poetry ought to be in such circumstances) as it was an attempt to collect and offer for consideration many possibilities.” (“11 September 2001, the Response of Poetry” 2001).

Also W. H. Auden’s “September 1st, 1939” was pressed into duty in the days following the attacks:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odor of death

Offends the September night. (Auden, “September 1st, 1939”).

Why have people turned to poetry at a time like this? “Isn’t there a contradiction here?” asked Mursi Saad El–Din in Al–Ahram Weekly Online, and then noted: “But then the ugly anger of Othello also produced beautiful poetry.” (El–Din 2001). Sven Birkerts, faculty member at Mount Holyoke College, attempted an explanation after reading Auden’s poem with his class: “We read poetry because we need something to hold against horror, something to place alongside it that is equally persistent. Not because poetry overturns or disarms horror, but because it helps restore the delicate inner balance we call sanity.” (Birkerts 2001).

Meaning in Libraries After September 11th?

People sought meaning in poetry after September 11th, but what of libraries? Have libraries helped restore sanity? The American Library Association’s American Libraries declares forthrightly on the cover of its November 2001 issue that “Libraries represent stability to a nation traumatized by terrorism,” and documents some of the responses in libraries across the United States, especially in New York City. According to the President of New York Public Library, “Many New Yorkers look to us to help bring some coherence, if not normality, back to the lives of our communities and our fellow citizens.” (Novacek 2001). And Leonard Kniffel, editor of American Libraries, emphasized that “Libraries represent stability to a nation.” (Kniffel 2001).

Sheila Intner has encapsulated the meaning of libraries and information centers in this time:

As I wrote this column and thought about the implications of September 11th, the place of libraries and librarians, archivists, records managers, and other information specialists seemed central to its every aspect. ... Information gathering and dissemination was, immediately, and still is, as you read this column, a critical factor in moving away from despair and on toward total recovery. Less dramatically, perhaps, but no less importantly to ordinary people, library collections were tapped and librarians helped locate appropriate readings, musical pieces, poems, and images for memorials, commemorations, and other recognitions of the events of September 11th. (Intner 2001)

Information gathering and dissemination and the sanity they represent to library users, for learning, livelihood, and recreation, as well as the freedom to exercise it, are very much at the center of the significance of this fall’s terrorist events, both before and after, for good and for ill. The Library Journal reported already in its October 1st issue that “Some of the men who hijacked the four U.S. planes September 11 apparently used public library computers to access the Internet and perhaps to communicate with each other.” (Rogers and Oder 2001).

Also in Europe, librarians were ready to respond with information resources that would answer patrons’ questions. The day after the tragedy, subscribers to Biblioteknorge, the nation–wide listserv for librarians in Norway, were discussing and sharing bibliographies about the Middle East and terrorism. During that discussion, however, Suzanne Bancel warned that people might “be overwhelmed by impressions and may not be ready yet for ‘matter–of–fact’ information.” In the same vein, Morten Skogly agreed with the caution that it was too early on the day after the attacks with no certain evidence to associate them with Middle East questions, and suggested that it might be better to postpone any showcasing of materials until it might again be possible to discuss these events in a rational and detached manner. Skogly did, however, also concede that it may even then have been too late to shed unbiased light on these questions. As if to confirm this observation, Ellen Vibeke Nygjelten, the director of Tolga Public Library, forwarded a challenge being circulated among the country’s mayors “to express their revulsion at the terrorist actions in the United States” with “a candlelight demonstration in all municipal and city halls.” (Biblioteknorge Discussion List 2001).

But there is another question of meaning and sanity in libraries that we need to look at, one that arises out of the thoughts penned by Lisa Ruddick in The Chronicle of Higher Education in November, who asserted that “People everywhere are taking stock of their values and their goals,” suggesting that “this sort of questioning” should lead “to real self–reflection” in the humanities, and, by implication, all fields. (Ruddick 2001).

Self–Reflection in Libraries?

Self–reflection in the area of library and information services should be indicated by a sense that something is different since September 11th. An international community of librarians was sought in order to discover if there was any sense of something new. Stumpers–L is “an email group or conference where Reference Librarians post questions which have them stumped. With a worldwide community of over 1,000 librarians and other experts sharing their knowledge and resources, Stumpers–L is the world’s largest and most versatile reference desk...” (Wonderful World of Wombats 2001). A message was sent in October 2001 to Stumpers–L, asking the following questions:

- Have any of you noticed any changes in the types of questions and even in the attitudes of patrons since the attacks?

- Have you noticed any changes in your own or colleagues’ attitudes in reference service or ways of relating to patrons? (Koren 2001b).

Responses sent privately to the author indicated that few changes were apparent in academic libraries, beyond an increase in the numbers of questions related to Islam and terrorism, Nostradamus and an increased interest in the news. Public librarians noted a spate of questions immediately after the attacks about the World Trade Center, the prophecies of Nostradamus, the location of various small towns in Pennsylvania, and addresses for various people.

Similar questions were sent to LIBREF–L, a moderated discussion list of issues related to reference service with a few non–U.S. members. The replies were much the same as those from the Stumpers subscribers. There were stories, also, of nervous patrons: “A patron we hadn’t seen before accosted one of our regular patrons, a lady from India. We didn’t hear what he said, but she protested that she wasn’t ‘from that country,’ and dissolved in tears. The man left the library immediately afterwards.” (LIBREF–L Archives 2001). There were also discussions regarding security in libraries: “For the most part libraries don’t implement adequate security e.g. guard at the door checking packages, requiring ID checks, requiring non–university people to identify and sign–in/sign–out.” During the author’s presentation at the Royal School of Librarianship and Information Science in Copenhagen, Denmark in December, 2001 (Koren 2001c), there were smiles of recognition concerning the Nostradamus queries and the subsequent discussion revealed very similar experiences.

A student in a basic reference class the author was teaching in the fall of 2001 made some insightful points in this connection during online class discussion:

- “...we are going to need to be more aware of issues related to free speech, including patron confidentiality and legal requirements.”

- “We are also going to need to more deeply confront our beliefs and our fears as we deal with all of the different people who come to us for service.”

- “This is already requiring more sensitivity in day–to–day dealings with the public in my experience at a public library.”

This brings to the fore the issues raised by the Patriot Act, issues that have been commented on in library periodicals outside the United States. For example, the Danish Bibliotekspressen, organ of the Danish Library Association, reacts to coming new laws and amendments to existing laws that contain provisions in conflict with the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights and the European Human Rights Convention, not only in the United States but also among several of her allies. (Nyeng 2001). Nyeng draws his readers’ attention to IFLA’s new “Statement on Terrorism, the Internet and Free Access to Information” which “proclaims that the libraries and information profession of the world will respond to these tragic events by redoubling our efforts to see free access to information and freedom of expression worldwide.” (IFLA 2001). The Norwegian periodical Bok og bibliotek voices the same concern in its December issue (“Biblioteka i USA” 2001).

The student raises an important question for education for library and information services: is it enough to simply focus on core competencies in professional education? The issues are perhaps discussed, but self–knowledge and sensitivity have not been the traditional fare in library schools. Perhaps there is a need to encourage self–reflection on how we can provide service in a time of insecurity both for our patrons and ourselves. Maybe it is time to consider the complete person: to develop an ideal professional persona for librarians and information workers.

Components of the Professional Persona

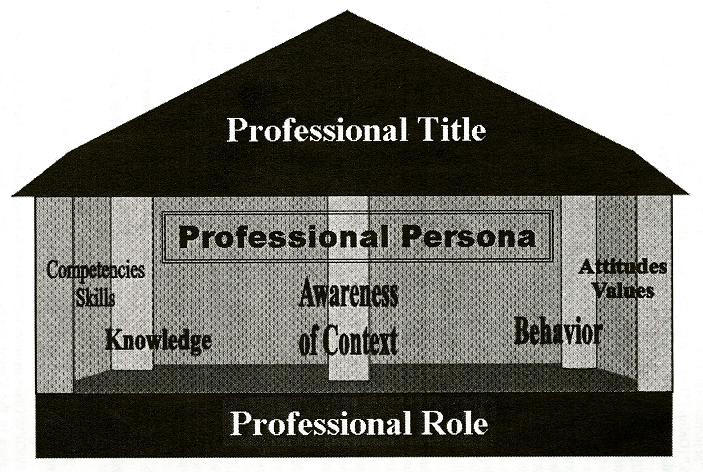

Figure 1 is an attempt at a graphical representation of the components of the professional person. This is the latest step in the author’s continuing attempt to define the elements that make up the professional self–image. The original model was presented in the author’s dissertation (1992) and published in articles in English (199l) and Norwegian (1995). That model, while attempting some synthesis, was not entirely conceptualized as an integrated whole, but simply as an aggregate of the components capability, behavior, and status, together with the background element of role. Later versions incorporated additional elements, such as professional knowledge and renamed others, calling “capability” “competencies/skills” and reforging “status” as “situation”, in an attempt to reconceptualize “status” to include the idea of professional context (Koren 2001a). This version presented here, on the other hand, attempts to suggest the cohesive whole of a self–aware professional personality through a 3–dimensional representation of a closed room.

In this model (fig. 1), professional role and professional title, or more precisely, the professional’s own conceptualization of these elements, are the foundation and the capstone, respectively. The outward manifestations of the professional persona in competencies and skills and behavior, as well as the professional’s attitudes and values and his or her awareness of the professional context and situation in which that person is working grow out of a perception of what constitutes the professional role that is considered appropriate. The professional title is the self–designation that he or she sees as most descriptive of that role. If these elements are integrated and combined in a conscious, coherent manner through reflection–in–action (Schon 1983), then the professional has an opportunity to build and develop the profession into a vocation that can help provide the sanity many are seeking in this difficult time.

Conclusion

This model of the professional persona is merely proposed here. The content of the elements, as well as the manner of their integration, not to say how to introduce the concept into education for library studies, will need considerable further thought and research. Donald Schon (1987) provided some useful strategies in Educating the Reflective Practitioner, but his initiative was not necessarily based on a holistic concept to the same extent as this. At a time when global awareness and sensitivity to ethnic, racial, religious, and international diversity is virtually being forced upon us by the “terrible beauty” that has been born, this proposal is worth further study.

|

| Figure 1 Components of the Professional Persona |

Works Cited

[a] “11 September 2001, the Response of Poetry.” [Online], 2001. Last Updated Christmas Day, 2001. Available from <http://www.geocities.com/poetryafterseptemberll2001/index.html>.

[b] Auden, W. H. [Online]. “September 1st, 1939.” as cited in Birkerts, 2001. Available from <http://www.mtholyoke.edu/offices/comm/oped/poetry.shtml>.

[c] “Biblioteka i USA fjernar ‘farleg’ informasjon.” [Libraries in the USA remove ‘dangerous’ information]. Bok og bibliotek, December 2001, 9.

[d] Biblioteknorge discussion list. 2001. Midtøsten tema [Middle East topics], in Archives , September, 2001, accessed November 5th, 2001. Database online. Available from National Library of Norway, Mo i Rana, Norway at <http://www.nb.no/cgi–bin/wa?A1=indO109&L=biblioteknorge&F=P&S=&O=D&H=0&D=0&T=1

[e] Birkerts, Sven. 2001. [Online]. “Disaster Calls Poetry to Action: Auden’s Verses Are Back At Work.” Mount Holyoke College Office of Communications, reprinting a piece from the New York Observer Monday, October 1, 2001. Accessed November 5th, 2001. Available from <http://www.mtholyoke.edu/offices/comm/oped/poetry.shtml>.

[f] Delepierre, Frédéric. 2001. [Online]. «En Belgique, c’est la psychose: l’anthraxest partout et nulle part.» Le Soir en ligne, 2001. Accessed November 5th, 2001. Available from <http://dossiers.lesoir.be/11sept/frappes/frappesp94.asp>.

[g] El–Din, Mursi Saad. 2001. [Online]. “Plain Talk.” Al–Ahram Weekly Online, Issue No.552, 20–26 September 2001. Accessed November 5, 2001. Available from <http://www.ahram.org.eg/weekly/2001/552/cu3.htm>.

[h] Feehily, Patricia. 2001. [Online]. “A globalisation of sorrow and sadness.” Limerick Leader, September 22nd, 2001, sec. Features. Available from <http://www.limerick–leader.ie/issues/20010922/feehily.html>.

[i] Gerrard, Nicci. 2001. [Online]. “Silent Witnesses: Special Report: Terrorism in the US.” [Online] Guardian Unlimited, The Observer, Sunday, September 16, 2001. Accessed November 5th, 2001. Available from <http://www.guardian.co.uk/wtccrash/story/0,1300,552782,00.html>.

[j] Intner, Sheila S. “After September 11th.” Technicalities, November/December 2001, 1, 4–5.

[k] Kniffel, Leonard. 2001. “Traumatized by Terrorism.” American Libraries, November 2001,12–18.

[l] Koren, Johan. 1991. “Towards an Appropriate Image for the Information Professional: An International Comparison.” Libri 41 (1991): 170–182.

[m] Koren, Johan. 1992. “A Comparison of the Views of Selected Library and Information Studies Educators in the United States and Scandinavia Concerning the Image of the Information Professional.” Ph.D. diss., The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, 1992.

[n] Koren, Johan. 1995. “Bibliotekaren og profesjonaliseringssyklusen: en sammenligning av bibliotekpedagogers syn på image og status i USA og Norden.” [The Librarian and the Professionalisation Cycle: A Comparison of the Views of Library Educators in Scandinavia and the United States.]. Norsk Tidsskriftfor bibliotekforskning 2, no. 1 (1995): 54–70.

[o] Koren, Johan. 2001a. “The Reference Professional in the Global Portal: Porter, Pathfinder or Pedagogue?” Proceedings of 11th Nordic Conference on Information and Documentation, Reykjavik, Iceland, May 30–June 3, 2001. See webpage at <http://www.bokis.is/iod2001/>.

[p] Koren, Johan. 2001b. “Reference Relevance after 9–11?” Discussion List. October 15th 2001.

[q] Koren, Johan. 2001c. “Reference Relevance after 9–11?” Invited presentation in Norwegian at Continuing Education Seminar for Digital Reference Librarians at the Royal College of Librarianship, Copenhagen, Denmark, December 4th, 2001.

[r] IFLA. 2001. [Online], “IFLA Statement on Terrorism, the Internet and Free Access to Information.” International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Committee on Free Access to Information and Freedom of Expression. Media Release, Thursday, October 04, 2001. Accessed November 5th, 2001. Available from <http://www.ifla.org/faife/news/ifla_statement_on_terrorism.htm>.

[s] Letvik, Tore. 2001 . [Online]. “Psykolog roser myndighetenes krisehåndtering.” [Psychologist praises how authorities are handling the crisis] Dagsavisen, October 20th 2001. Journal online. Accessed November 5th, 2001. Available from <http://www.dagsavisen.no/utenriks/apor/2001/10/611088.shtml>.

[t] LIBREF–L Archives. 2001 . LIBREF–L email discussion list, October 2001 , Week 3. Online at <http://listserv.kent.edu/scripts/wa.exe7A1=indO11Oc&L=libref–l>.

[u] Novacek, Julie. 2001. “Coping in New York.” American Libraries, November 2001, 18–19.

[v] Nyeng, Per. 2001. “IFLA og 11.September.” [IFLA and September 11th]. Bibliotekspressen, no. 18, October 16, 2001, 548.

[w] Ramotar, Mark. 2001. [Online]. “Anthrax fear: White powdery substance found in mail.” Guyana Chronicle, November 22 2001, sec. Archives. Available from <http://www.guyanachronicle.com/ARCHIVES/archive%20%2022–11–01.htm#Anchor—1751>

[x] Rogers, Michael and Norman Oder. 2001 . “Did hijackers use internet at PLS?” Library Journal, October 15, 2001, 17.

[y] Ruddick, Lisa. 2001. [Online]. "The Near Enemy of the Humanities is Professionalism." The Chronicle of Higher Education, November 23 2001, sec. Chronicle Review. Available at <http://chronicle.com/free/v48/13b00701.htm>.

[z] Schön, Donald. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

[aa] Schön, Donald. 1987. Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey–Bass, 1987.

[bb] Thip–osod, Anjira Assavanonda Manop. 2001. [Online]. “16 suspect letters found: All addressed to gain maximum publicity.” Bangkok Post, Thursday, 18 October 2001, sec. General News. Available from <http://scoop.bangkokpost.co.th/bkkpost/2001/october2001/bp20011018/news/l8Oct2001_news04.html>.

[cc] “Wonderful World of Wombats: The Unofficial Stumpers–L Page.” [Online], 2001. This site is maintained by T.F. Mills, wombat@regiments.org. Accessed November 7th, 2002. Available from <http://www.regiments.org/wombats/>. The official Stumpers–L website is at <http://domin.dom.edu/depts/gslis/stumpers/>.

[dd] Yeats, W. B. “Easter 1916.” [Online]. The Literature Network, 2000–2001. Accessed November l2th, 2001. Available from <http://www.online–literature.com/yeats/779/>.

[ee] ZDF Magazin–Heute. 2001. [Online]. “Angst vor Post mit Pulver: Trittbrettfahrer schüren Angst vor Milzbrand–Anschlägen.” [Fear of Mail with Powder: A Freeloader Stokes the Fears of Anthrax Attacks] ZDF, 2001. Accessed November 5th, 2001. Available from <http://www.heute.t–online.de/ZDFheute/artikel/0,1367,MAG–8775–7755,00.html>.

About the author

Johan Koren is Libra Professor of Library and Information Services, University of Maine at Augusta. Email: JKoren@maine.edu.