Subject Specialisation at the University of Botswana Library and the Rand Afrikaans University Library: A Comparative Study

Abstract

The University of Botswana Library and the Rand Afrikaans University Library have both adopted a subject specialisation approach in the delivery of services. This article seeks to establish similarities and differences in the application of subject specialisation in the two libraries. The comparisons reveal interesting findings from which both can learn and improve services. Subject librarians at the University of Botswana spent relatively more time on technical related functions, while the information librarians at Rand Afrikaans concentrate more on customer–centred services. Automation is viewed as an indispensable tool for quality services in both cases. The article concludes by highlighting the importance of customer service, which is inherent in subject specialisation.

Introduction

This article is based on the author’s twelve years’ experience as Education subject librarian at the University of Botswana Library (UBL), and three months’ sabbatical leave spent at the Rand Afrikaans University library (RAUL). Subject librarianship at UBL is considered, followed by an examination of the practice of information librarians at the RAUL.

The article stresses the positive aspects as well as disadvantages of subject specialisation, and makes recommendations for improving services in these libraries. During the past forty years, there has been a major shift from a functional to a subject–based approach among academic libraries world–wide. This is due to the new emphasis on the maximum exploitation of resources and a focus on customer service, rather than on the conservation role of the library (Bastiampillai and Havard Williams 1987). Accordingly, there have been changes in staffing patterns and structures; notably a new breed of professionals called subject librarians has emerged. The main functions of subject librarians are to develop and organise the collections, provide subject–specific reference and information services, and subject–oriented library instruction.

UBL and the RAUL are two academic libraries in Southern Africa that have adopted a subject–centred library organisation. In UBL, professional librarians are referred to as subject librarians, while the subject specialists at RAUL are termed information librarians. The philosophy of subject librarianship differs from one country to another, and in some cases from one university to another within the same country. This article is therefore a comparative study of subject specialisation in these libraries.

Definitions

A subject librarian or information librarian is a subject specialist who has been given the responsibility for providing services in assigned subject areas, In the academic research library, these services include one, but increasingly two or more, of the following: collection development and skilled assistance to customers in maximizing the use of the collection.

Ogundipe (1990) explained that subject specialist is used as an umbrella term for many variations, such as subject librarian, information officer, library liaison officer and faculty librarian. For the purposes of this article, the preferred definition is that of Feather and Sturges (1997): a librarian with special knowledge and responsibility for a subject or group of related subjects.

Literature Survey

Subject specialisation is a relatively recent phenomenon in Africa compared to industrialized countries. Several reasons account for this, but this is mainly due to lack of qualified personnel and limited funding (Fadiran 1992), and also the low status of the profession in Africa (Ochai 1991).

But subject specialisation in Europe and North America has been practised for well over fifty years. This topic has been well documented in several studies in the past four decades. Woodhead (1982), for example, traced the evolution of subject specialisation in British university libraries, and identified five categories of such specialisation. Holbrook (1984) studied the problems and techniques of establishing liaison with the faculty and students in the British university setting. Bastiampillai and Havard Williams (1987) identified in their study three types of organisational patterns in university libraries, and the problems of staffing associated with this arrangement. Gibbs (1993) explored scientific special librarians, and the effects of those with subject knowledge compared to those without special subject qualifications. More recently, Walton, Day and Edwards (1996) described the changing role of subject specialists in the UK in the era of the information superhighway. The conclusion is that there are vast advantages derived from subject specialisation.

There are however, fewer studies on subject specialisation in developing countries. Avafia (1983) studied the concept of subject specialisation in the context of some African university libraries. He recommended that African university libraries should consider adopting this new service approach. Ogundipe (1983) likewise advocated a system of library management based on subject specialisation for African university libraries. Bandara (1986) considered subject specialisation in university libraries in developing countries, and identified problems peculiar to African librarians. Prozesky (1986) described the major functions of subject librarians at the university of Natal, South Africa, as primarily technical duties, other than information retrieval. Ochai (1991) examined the Nigerian university library situation. He argued for subject librarians with specific subject qualifications in addition to library science, although there is a shortage of librarians of this calibre in Africa.

Jenda (1994) undertook a time management study of UBL’s adoption of the subject centred library model. She examined the multiple functions of subject librarians; both positive and negative aspects of this approach are discussed. However, it would appear there are more disadvantages than advantages in this case.

Background Information

University of Botswana

The University of Botswana was established by an act of Parliament in 1982. The University offers a wide range of undergraduate and graduate programs in six faculties of Business, Education, Engineering and Technology, Humanities, and Science and Social Sciences. Over the years, this University has evolved to become a regional centre of excellence in select disciplines. This has a direct bearing on the provision of adequate curriculum–based information sources by the university library.

UBL consists of the main campus library and the two branch libraries, one at the Faculty of Engineering and Technology (FET) and the other at the Centre for Continuing Education (CCE) in Francistown. The total book collection is about 250,000 volumes, 1,500 periodical titles and some 35 CD–ROM title subscriptions.

The library has a full complement of 25 professionals and 90 paraprofessional staff, and serves a population of some 9,000 students, 500 faculty members, plus 300 registered external borrowers. The two branch libraries are connected to the main library network in Gaborone. The library is partially automated, and is a participant in the regional library network, SABINET (South African Bibliographic NETwork).

UBL adopted subject specialisation in 1981, and introduced four teams of subject librarians: education, humanities, science, and social sciences. The two new teams added recently are business and engineering, and technology. The minimum entry level requirements for a subject librarian are a relevant subject degree other than library science, plus a professional library qualification, i.e. a Postgraduate diploma or Masters in Library Science.

A subject librarian is normally assigned one or a cluster of related subjects. A subject team consists of two or more librarians. The primary function of a subject librarian is collection development, subject indexing, reference/information services and user education in liaison with relevant departments, The philosophy of subject librarianship is that it provides the best climate for customer services through the strong liaison function built into it. Under this arrangement, subject librarians are directly under the Deputy Librarian, but they are answerable to the three Coordinators for everyday functional activities. The administrative structure is depicted in Appendix A. This structure must be considered transitional, as the university library is undergoing restructuring.

The Rand Afrikaans University

The Rand Afrikaans University (RAU) was established in 1967 as the academic home of the Afrikaans–speaking students in the Witwatersrand area. The new campus, which was inaugurated in 1975, is a high–tech, compact and multi–functional university complex in the heart of Johannesburg.

RAU has gradually changed its perspective by accommodating a widely divergent student population from all language groups within and outside South Africa. Today, the two languages of instructions are Afrikaans and English. RAU has a student population of 23,000 and a complement of more than 400 permanent academic staff. It consists of six faculties of Arts, Education and Nursing, Economics and Management Sciences, Engineering, Law, and Science. In addition to an increasing number of undergraduate students, there are a number of postgraduate courses in at least eighteen academic departments. In recent years, RAU has introduced various distance education and continuing education courses in a number of disciplines.

RAUL has a total of 440,000 volumes and some 44 CD–ROM titles. There are four small departmental periodicals libraries, which keep current issues only in the faculty of Science.

RAUL adopted subject specialisation in 1967, and subject specialists were then referred to as subject librarians until the 1980s, when they changed to information librarians, in order to capture their increased role in information provision. The academic requirements for information librarians are one of the following professional qualifications: Lower or Higher diploma, Honours or Masters degree in library and information science; any additional subject degree is an added advantage rather than a requirement.

The two major areas of responsibility for the information librarians are information management and user education. Information librarians conduct literature searches and undertake bibliographic instruction for students and academic staff in their respective departments.

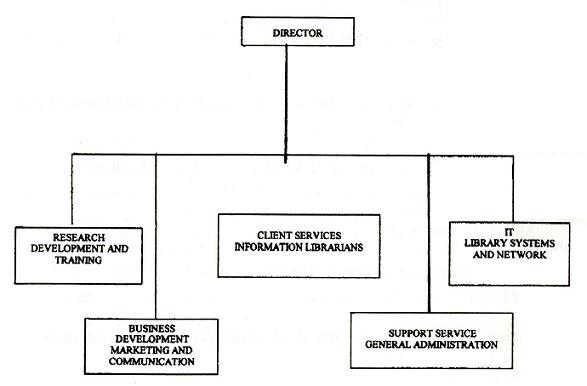

The organisational chart shows a somewhat flattened structure consisting of library management at the centre, and five sections around it. Information librarians are at the heart of client services, and they are also an important part of the Research and Development training section. The organisation chart for RAUL is represented in Appendix B.

Purpose and Methodology

As noted, this article compares the practice of subject specialisation in two university libraries in Botswana and South Africa. It seeks to establish the similarities and differences in the application thereof, and thereby suggests ways in which the system can be improved. The author works at UBL, and has spent about three months at RAUL. He has therefore observed the practice of subject specialisation in the two libraries. The observational technique used in the study has some shortcomings, in that the observation at RAUL was relatively shorter compared to that of UBL.

A twelve–item questionnaire was sent to all subject specialists in these two libraries, soliciting information on the following major areas: qualifications; subject specialisation, professional workload breakdown, primary functions of subject librarians and the impact of automation on the role of subject librarians. (See Appendix C).

Findings and Discussion

Out of fifteen questionnaires posted to RAUL, ten were returned, which represents an 80% response rate. At UBL, twenty questionnaires were administered and a 100% response was recorded. These questions focused on academic qualifications required from subject and information librarians, the professional workload, the advantages and disadvantages of subject specialisation, and the impact of automation on subject specialisation.

Table 1 below shows the breakdown of professional workload in percentage:

| Libraries | Collection Development | Reference/ Information | User Education | CD–ROM Searches | Faculty Liaison | Classification and Indexing | Other |

| UBL | 20% | 15% | 19% | 8% | 13% | 21% | 4% |

| RAUL | 7% | 26% | 26% | 28% | 10% | 2% | 1% |

Table 1 represents a typical breakdown of the professional workload of subject specialists in both libraries. Overall, it is quite clear that information librarians at RAUL spent a lot more time in customer–centred activities; this accounts for almost 90% of their time. The remaining 10% of the workload is allocated to technical and other related work.

On the other hand, subject librarians at UBL spent 41% of their time on collection development and information organisation. User services took up 45%, and the remaining 15% was used for other tasks. This shows the hybrid model of subject specialisation at UBL as suggested by Jenda (1994). Bastiampillai and Havard Williams (1987) referred to this as a combined functional/subject pattern, in which the staff have a dual role of functional approach and subject orientation.

Furthermore, it is clear that the subject librarians at UBL spent 41% of their time on collection development and information organisation, compared to a mere 9% by their counterparts at RAUL. This could be explained partly by the fact that all subject librarians at UBL have a relevant subject degree in addition to the professional qualification, and therefore have greater autonomy over selection materials. Secondly, the budgetary allocation policy of each library may also influence the level of participation by faculty members.

Information librarians at RAUL, have a professional qualification, but not necessarily a subject degree. Consequently, the academic staff have greater control over the selection of library materials. However, this argument is contested and challenged by Williams (1991), who maintains that a particular kind of knowledge beyond subject specialisation is required for selection.

Question 10 solicited information about the positive aspects of subject specialization. More than 70% of the respondents mentioned that this arrangement promotes greater partnership with both academic staff and students, and thereby encourages effective and efficient delivery of services to customers. This approach provides for holistic service and a better understanding of the requirements for overall effective service in a given subject.

Subject librarianship at UBL in particular has ushered in a new era; there is greater work variety, and a better chance for increased intellectual stimulation and professional development. 85% of the librarians felt that they are in a better position to serve their customers, they become familiar with their collections, and develop a much broader perspective of the information needs of both students and staff.

In question 11, respondents were asked about the disadvantages of subject specialisation. Some of the disadvantages mentioned are that it is an expensive operation, and demands professional staff with a specific subject degree in addition to professional qualification. The implication of this is that someone can only fill a subject librarian position with a qualification beyond a Bachelor’s degree. Jenda (1994) has confirmed that a subject–centred library organisation requires more professional staff to run effectively than a functional type of library.

Furthermore, subject specialisation is likely to promote parochial–minded professionalism, in that one may specialise at the expense of other professional duties. Contrary to other views, 55% of UBL respondents felt subject librarians are expected to do multiple tasks. These include all professional duties such as collection development, classifying and indexing, reference and user education programs in addition to other library routines; this is regarded as an overload. This is perhaps in line with the warning from Bastiampillai and Havard Williams (1987) that academic libraries adopting subject approach must ensure subject librarians are not unduly weighed down by routine work.

The final question focused on the impact of library automation on the role of subject librarians. RAUL is fully automated and offers more customer services than UBL, which is only partially automated. Library automation or computerization has been embraced as an indispensable tool rather than a threat by both libraries. This is because, since librarians are now able to offer better and faster services than ever before, the quality of such services is also enhanced. Automation ensures timely and accurate provision of relevant information from national as well as international sources. Above all, automation empowers librarians as gatekeepers of information more than ever before. And so the issue of librarians being replaced by computers is out of question. It is more likely that those librarians who keep well abreast of information technology developments will replace the traditional librarians.

Conclusion

Subject specialisation is on the increase in most academic libraries. Generally, the advantages of this form of organisation outweigh the functional approach in many ways. The respondents from the two university libraries articulated these advantages.

UBL and RAUL have changed from the classical hierarchical structure to a matrix environment, which encourages a participatory management style. Similarities that can be drawn from these libraries include a common philosophy, and subject specialisation as the basis of library organisation. The main functions of subject librarians are customer–focused rather than function–oriented, though to a varying degree.

Both libraries have technical services sections that focus on managing and maintaining a quality database. Library automation is used to enhance services and facilitate access to local and remote databases. There are, however, differences in the application of subject specialisation in these two libraries. In particular, the UBL subject–oriented organisation is more of a hybrid, in that it uses aspects of both traditional organisation and subject–centred. It has grafted subject specialisation on to the traditional functional structure.

On the other hand, subject specialisation at RAUL is not pure either, in the true sense of the German model of academic libraries, where the emphasis is on appropriate academic qualifications, and the predominance of book selection (Williams 1991). Subject specialists spent more time on customer services and very little time on book selection.

Whatever the case, the challenges facing subject specialists include the increase in numbers of students. Some of them arrive without any library skills, others with limited exposure to information seeking skills. Subject librarians therefore have to come up with information literacy skills packages appropriate for both groups. In addition, subject specialists have to take cognizance of new teaching techniques such as resource based learning. The success of this depends largely on building good relations with faculty members; liaison with academic staff forms the cornerstone of subject specialisation.

Subject specialisation in African academic libraries is here to stay; it is difficult to imagine libraries reverting to the functional approach in this era. In view of the growing importance of information technology and the trend towards a student–centred approach to learning, the need for subject–centred orientation in libraries becomes even more crucial. Subject librarians at UBL would do well to refocus their attention on more user-centred services like database search services, the more so with the recent increase in the graduate student population, who come with sophisticated research needs. RAUL information librarians should empower themselves to participate fully and actively in collection development, if their subject specialisation is to be meaningful.

Subject specialisation is a dynamic; it has to be reviewed from time to time in an attempt to improve and introduce innovative and quality services to customers.

Bibliography

a. Avafia, K.E. “Subject Specialisation in African University Libraries.” Journal of Librarianship 15–3 (July 1983): 183–205.

b. Bandara, Samuel B. “Subject Specialists in University Libraries in Developing Countries: The Need.” Libri 36–3 (1986): 205–206.

c. Bastiampillai, Marie Angela and Williams, Peter Havard. “Subject specialisation Re–Examined.” Libri 37–3 (Sept 1987): 196–210.

d. Fadiran, D O. “Subject Specialisation in Academic Libraries.” International Library Review 14 (1982): 41–46.

e. Feather, John and Sturges, Paul. International Encyclopedia of Information and Library Science London: Routledge, 1997.

f. Gibbs, Anne-Beth-Liebman. “Subject Specialization in the Scientific Special Library.” Special Libraries 84 (Winter 1993): 1–8.

g. Hay, Fred J. “The Subject Specialist in the Academic Library: A Review Article” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 16–1 (March 1990): 11–17.

h. Holbrook, A.“The Subject Librarian and Social Scientists: Liaison in a University Setting.” Aslib Proceedings 36–6 (June 1984): 269–275.

i. Jenda, Claudine Arnold. “Management of Professional Time and Multiple Responsibilities in the Subject–Centered Academic Library.” Library Administration & Management 8–2 (Spring 1994): 97–108.

j. Ochai, Adakole, “The Generalist Versus the Subject Specialist Librarian: A Critical Choice for Academic Library Directors in Nigeria.” International Library Review 23–2 (June 1991): 111–120.

k. Ogundipe, O. “Subject Specialisation in a University Library.” African Journal of Academic Librarianship 1–2 (December 1983): 52–56.

l. Oliobi, Mathew Ikechukwu. “Tapping the Subject Background of Librarians: The University of Port Harcourt Library Experience.” Library Review 43–3 (1994): 32–40.

m. Parker, S. Jackson. “The Importance of the Subject Librarian in Resource Based Learning: Some Findings of the IMPEL2 Project.” Education Libraries Journal 41–2 (Summer, 1998): 21–26.

n. Prozesky, Leonore and Cunningham, Wendy. “Subject Librarian Work at the University of Natal Pietermaritzburg.” Wits Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 4 (December 1986): 96–112.

o. Walton, G., Day, J and Edwards, C. “Role Changes for the Academic Librarian to Support Effectively the Networked Learner: Implications of the IMPEL Project” Education for Information 14–4 (1996): 343–350.

p. Williams, L. B. “Subject Knowledge for Subject Specialists: What the Novice Bibliographer Needs to Know.” Collection Management 14–3/4 (1991): 31–47.

q. Woodhead, P. A. and Martin, J. V. “Subject Specialisation in British University Libraries: A Survey.” Journal of Librarianship 14–2 (April 1982): 93–108.

Appendix A. UBL organisational structure (under review – April 1999)

|

Appendix B

Raul Organisational |

|

Appendix C

Questionnaire

Kindly complete this short questionnaire and return to me as soon as possible. Thank you in anticipation for your precious time.

- What is your professional qualification?

- Do you have any other degree or diploma in a subject other than librarianship?

Yes_________ No_________ - If your answer is Yes in 2, in which field is your degree Education

Humanities__________________ Science__________________

Social Sciences___________________________

Other (Please state__________________________________) - 1s this qualification a requirement for the your job?

Yes_________ No_________ - Are you handling subjects in your field of subject specialisation only?

Yes_________ No_________ - If the answer is NO in 5 above, are you comfortable/confident in handling other subjects?

Yes_________ No_________

a) How many graduate students do you have in your section?

_________________________________________________ - Briefly state the mission statement of your library.

- What would be a typical breakdown of a professional (subject librarian) work load in percentage terms of your library

- What in your opinion is the primary function of the Subject Librarian/Information Librarian?

- Which are the important positive aspects of this type of arrangement (subject specialisation) of an academic library?

- What are the main disadvantages of subject specialisation?

- What is the role of library automation in your role as a subject or Information librarian?

| Activity | Percentage (%) |

| Collection development | |

| Classification and indexing | |

| Information and reference work | |

| User education (Orientation and BI) | |

| On line bibliographic searches and CD ROM searches | |

| Other (Please specify) |

About the author

Edwin Qobose is Senior Assistant Librarian at the University of Botswana. email qobose@mopipi.ub.bw.