Rural Community Information System in Nigeria: Imo State Project Report

Abstract

The article describes a rural community information system project in Imo State. It discusses the community analysis process and profiles the populations studies. The authors also assessed the organizational resources of the project, the services provided, as well as its achievements and obstacles. The article concluded with recommendations for better funding, inter-agency cooperation, service location, and staff training.

Introduction

Rural communities in Nigeria constitute more than 80 percent of the Nigerian population of over 88 million people. Of this percentage, 70 percent are illiterate and are engaged in peasant farming, petty training, artisan work, or other semi-skilled labour. This means that most library services which are urban based do not reach them. How far they have absorbed other public or government information for use in development processes is yet to be ascertained. The focus of the Federal Military Government of Nigeria has been on how to alleviate the information deprivation of the rural majority. In order to alleviate the rural poverty and deprivation, the Federal Government of Nigeria established the following organizations:

(1) DFRRI -Directorate of Food, Roads, and Rural Infrastructure (1986)

(2) BLP - Better Life Programme for Rural Women (1985)

(3) PBN - Peoples Bank of Nigeria (1990)

(4) MAMASER - Mass Mobilization for Economic Recovery, Self-Reliance, and Social Justice (1987)

(5) Nomadic Education (1989)

Objectives

The major objectives of this paper include the following:

(1) To report practical efforts of rural community information services as practiced by the Imo State Library Board, Imo State, Nigeria

(2) To highlight some research findings on the information needs, community analysis, communication channels, or information transfer channels in rural areas, and the patterns of tasks performed in rural areas

(3) To serve as a guide to public libraries that have established or intend to establish rural community information centres in Africa

While the research findings do not claim to be exhaustive, this paper will, no doubt, throw some light on how rural community information services are practiced in Imo State, Nigeria, and serve as a basis for comparison with other efforts being made in Africa and other developing countries.

Definition of Terms

Rural Community

The term "community" denotes "a collection of people who occupy a given geographical area, who live together and engage in political and economic activities and who essentially constitute a self-governing social unit with some common values and experiencing feelings of belonging to one another."[1]

A community may be a village, a town, or even a city, and must possess the basic characteristics of shared belief system—territory; bond of followership; religion, if it is based on the possession of a common faith; or academic, if it is concerned with teaching and learning. Any of this classification may be urban or rural in nature depending on access to the basic necessities of life.

A community, therefore, is considered rural when it lacks the basic social infrastructures, such as pipe-borne water, electric power supply, good roads, good schools, health care institutions, and telecommunications.

Information System

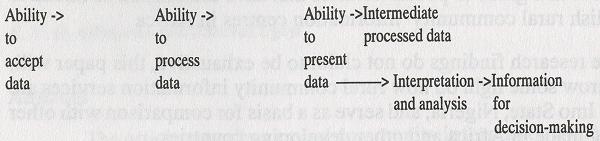

A system is defined as "a combination of interrelated elements, or sub-systems, organized in such a way as to ensure the efficient functioning of the system as a whole, necessitating a high degree of co-ordination between the sub-systems, each of which is designed to achieve a specific purpose."[2] An information system, therefore, is any scheme that has the ability to accept, process, present, update, and modify data, and to combine data sets originating from different sources.

The sequence of functions of an information system is illustrated below.

|

| Figure 1: Sequence of Functions of an Information System [3] |

Literature Review

That the rural dwellers have basic information needs is no longer a matter of conjecture. Rather, their information needs have been empirically determined. Information need is a desire by an individual or group for information for rational decision-making on life's competing options. Determining the delivery of the information needs of rural dwellers is a pre-requisite for effective and responsive library and information services. Ogunsheye,[4] Opara,[5] Aboyade,[6] Adimorah,[7] and Williams[8] had, in separate surveys, identified the information needs of rural communities in different parts of Nigeria. Their needs pertain to agriculture, public affairs, health, education, culture, business opportunities, and community development. Most of the rural population lack basic reading skills, so it is appropriate to repackage services that appeal to their visual and auditory senses. In an experiment in the provision of information services in a rural setting, Aboyade [9] gave details of community survey to identify rural information needs; expounded on a range of services deemed suitable for people who are essentially illiterate, and suggested how to carry out information exchange in a rural setting.

Many change agencies abound in the rural communities where they seek to reach the rural dwellers with packages to change their social conditions. They disseminate their respective organisational information, and differ in purpose, interest focus, activities, and operational style. They possess the capacity to provide facts as the basis for socio-economic reform, and maintain well–beaten information transfer channels. However, they lack resource–based centres to support their work. Aboyade [10] and Adimorah [11] [12] [16] have emphasized the role of a rural community information centre in coordinating the information dissemination activities of the various change agencies domiciled in the rural communities.

Against the back-drop of an unpleasantly high rate of failure with rural development projects in Nigeria in the past, Aboyade propounded a holistic rural development information system which would seek to boost communication and information transfer in the development process. She contended that a rural-based library can serve as an innovative institution for meeting the information requirements of the rural dwellers who are illiterate, but not unintelligent, and at the same time, help to reinforce the effectiveness and efficiency of the change agencies found in the countryside.

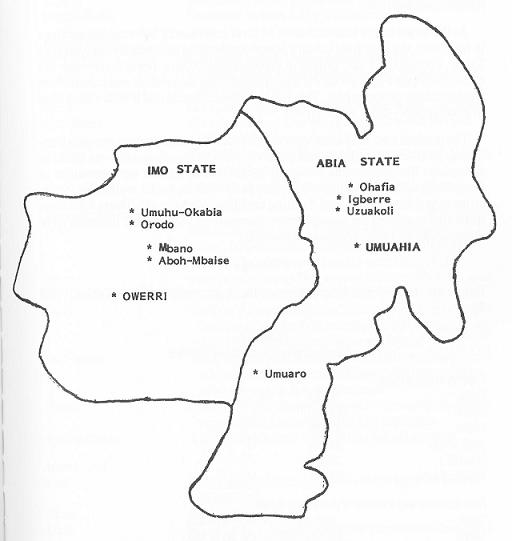

|

| Figure 2: Former IMO State of Nigeria |

Community Needs Analysis

Library services cannot be established in a vacuum. There must be a substance of needs. The identification of the information needs of the potential patrons' community is a pre-condition for providing effective library and information services.

At the dawn of the establishment of rural community information services in Imo State, the Imo State Library Board conducted a community analysis (see Table 1 below) of six different communities where library services are maintained (see Fig. 2), with the aim of identifying the profiles and information needs of these communities. This was a tedious exercise and it took a long time to accomplish—from 1986 to 1991.

The method used was a survey, and the research instruments were questionnaires, interview schedules, interview schedules, and observation. The questionnaire was made to administer the instruments randomly as so to obtain a fair representation of farmers, pensioners, teachers, students, petty traders, social welfare workers, artisans, public servants, non-farming unskilled workers, etc. Those who were illiterate completed the questionnaire themselves; whereas the illiterate were interviewed and their responses recorded.

Table 1

Community Analysis: Profiles

| Population (inhabitants) | |

|---|---|

| Orodo | 42,059 |

| Mbano | 498,685 |

| Ohafia | 311,099 |

| Aboh-Mbaise | 369,365 |

| Uzuakoli | 23,073 |

| Umuahu-Okabia | 15,434 |

| Area (hectares with a density of persons per sq. kilo.) | |

|---|---|

| Orodo | 2,590 with 834 persons per sq. kilo. |

| Mbano | 33,320 with 768 persons per sq. kilo. |

| Ohafia | 46,270 with 170 persons per sq. kilo. |

| Aboh-Mbaise | 30,620 with 619 persons per sq. kilo. |

| Uzuakoli | 3,650 with 325 persons per sq. kilo. |

| Umuahu-Okabia | 340,000 with 233 persons per sq. kilo. |

| Literacy Level | |

|---|---|

| Orodo | Between 30-35%; 13 primary and 5 post primary schools. |

| Mbano | No statistics; 61 primary schools. |

| Ohafia | No statistics; 15 primary and 19 post primary schools and commercial schools. |

| Aboh-Mbaise | No statistics; 57 primary, 12 secondary and 11 commercial and vocational schools. |

| Uzuakoli | No statistics; 5 primary, 2 post primary and 2 vocational schools. |

| Umuahu-Okabia | No statistics; 3 primary and 1 post primary school. |

| Cultural Lifestyle | |

|---|---|

| Orodo | Rich cultural heritage. Traditional attachment to land. |

| Mbano | Subsistence farmers. Cultural attachment to land. The coming of age ceremony called Iwaka. |

| Ohafia | Rich cultural heritage. Great cultural attachment to land. Yam festival. |

| Aboh-Mbaise | Rich cultural heritage. Great cultural attachment to land. New yam festival and Oji Mbaise, a form of festival. |

| Uzuakoli | Mixture of Igbo cultural heritage as an ancient slave trade route. New yam festival celebrated. |

| Umuahu-Okabia | Rich in culture; small scale farmer. New yam festival celebrated |

| Recreational Resources | |

|---|---|

| Orodo | Deficient. No tourist facility. Traditional dances, e.g. "Eekeleke" and "Owu". Local hotels (palm wine bars) and eating houses available. |

| Mbano | No recreational resources. The community civic centre serves as a festival gather place. Playground for local sports. |

| Ohafia | "Obu Nkwe" at Asga, and Amaekpu cave. Traditional Ohafia war dance in a popular form of entertainment; dotted with local eating houses and drink parlours. Civic centres built by age-graders are used for communal gathering. |

| Aboh-Mbaise | "Mbari" located at Umuaamodi Nguru, wildlife at Lagwa and the Oburudu of Ngura as tourist attractions. Traditional dances by men such as Abigbo are a regular form of entertainment. |

| Uzuakoli | Civic centres built by the communities exist. Presence of Obi as a meeting place for elders. Local hotels and drinking parlours exist. |

| Umuahu-Okabia | A few Mbari centres. Small local palm wine bars and restaurants. |

| Income Levels | |

|---|---|

| Orodo | Average monthly income of N135 for unskilled labour and N230 for skilled labour. |

| Mbano | Subsistence level. |

| Ohafia | Subsistence agriculture. Average monthly income of N230 for unskilled worker and N300 for skilled worker. |

| Aboh-Mbaise | Subsistence farming. Average monthly income of N240. |

| Uzuakoli | Subsistence. Average monthly income N230. |

| Umuahu-Okabia | Subsistence root crop farmers. Average monthly income N230. |

| Community Information Resources | |

|---|---|

| Orodo | Community-built library and information centre handed over to Imo State Library. |

| Mbano | Branch library of Imo State Library Board. |

| Ohafia | A functional library built by Oka-Ome age group of Amaekpu and handed over to Imo State Library Board. |

| Aboh-Mbaise | A functional community library built by women in Lagos and donated to Imo State Library Board. |

| Uzuakoli | A functional community library built by the community and handed over to Imo State Library Board. |

| Umuahu-Okabia | A community-built library donated to Imo State Library Board. |

Table 2

Summary of Usable Returns by Community

| Community | Sample | Size | Usable Returns % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ohafia | 200 | 177 | 85.05 |

| Mbano | 200 | 187 | 92.00 |

| Uzuakoli | 210 | 190 | 90.47 |

| Aboh-Mbaise | 210 | 188 | 89.53 |

| Umuahu-Okabia | 257 | 232 | 90.27 | Orodo | 270 | 240 | 88.8 |

Research findings reveled that Imo State is an administrative entity within the Igbo tribe, and occupies a relatively homogeneous ecological area in the oil palm forest belt in Nigeria. There are significant similarities in cultural lifestyles and economic activities. The Igbos have a traditional attachment to their roots and regard their native homeland as a place to retire to after long sojourns in the cities.

Subsistence agricultural and non-farming economic activities form the bedrock of the people’s economic existence. The notable economic activities include root crop farming, palmwine tapping, raffia works, petty trading, wood and metal works, unorthodox orthopaedics, animal husbandry, pottery, teaching, and business entrepreneurship (see Table 3). The monthly average income level of the rural population of the Imo State is N135, or N230 for skilled workers.

The literacy level of the state is about 50 percent, and among the rural population, only about 28 percent of the men and 23 percent of the women claim to be able to read and write. A wide range of recreational resources abounds within these communities, such as civic centres which serve as meeting points for important political, social, and festive functions; local restaurants and hotels; cultural dances and festivals; and a few tourist attractions.

Table 3

Pattern of Tasks Performed by Respondents

| Orodo | Mbano | Ohafia | Aboh-Mbaise | Uzuakoli | Umuahu-Okabia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palmwine tapping | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Indigenous orthopaedics | * | * | * | |||

| Raffia works | * | * | ||||

| Petty trading | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Wood works | * | * | * | * | ||

| Artisanry | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Subsistence farming | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Pottery | * | |||||

| Hunting | * | * | * | |||

| Rural business enterprises | * | * | * | |||

| Butchers | * | * | ||||

| Blacksmiths | * | * |

Communication channels between these communities include mass media, gossips, town criers, community leaders, local government councils, the church, and the community public library. It is important to note that out of the six communities surveyed, five built their respective community libraries through communal efforts. Development through self-help efforts is a unique characteristic of the Igbo tribe.

Because of the homogeneity of the communities, there were many similarities in their responses. The areas of information needs were health, education, occupation, problems of daily existence, political and governmental affairs, and recreation. The implications herein are the expressed desire by the rural dwellers for functional and recreational information, which clearly point out the impact of the change agencies on the countryside. Many of the change agencies are yet to have the desired impact in the rural areas. This short coming seriously undermines the realization of the lofty goal of integrated rural development. Therefore, the desirability of rural development information services should be reinforced.

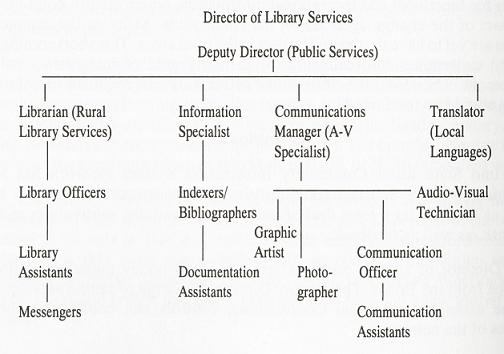

Organization

The Imo State Rural Community Information System Network has a hierarchical structure. Substantial authority has been delegated to the network's staff so as to allow for a great deal of innovation, creativity, motivation, and hard work, as well as feedback.

The Director of Library Services sets out broad policy guidelines with clearance from the Board. The Deputy Director in charge of public services, with the assistance of Zonal Coordinators, controls and coordinates the activities of the network.

The other staff include the following:

(1) Librarian (Rural Library Services) - Responsible for library services to the rural community. He also handles oral history documentation.

(2) Information Specialist - Responsible for the dissemination of information, indexing and abstracting services, and compiling bibliographies and rural community directories.

(3) Communications Manager or Audio-Visual Specialist - Organizes film shows, seminars and workshops, meetings, extension/outreach services, community walks.

(4) Translator - Handles the translation and reproduction of information into the vernacular.

(5) Agricultural Extension Officer - Repackages agricultural literature into simplified handbooks and leaflets.

(6) Graphic Artist - Charged with creating and designing aesthetic posters and other visual information matters.

The above-mentioned professionals are ably assisted by library officers, documentation officers, photographers, graphic assistants, audio-visual technicians, stenographers, messengers, and other assistants.

The organizational structure is illustrated here.

Figure 3

Organizational Structure

|

Rural Information Services

Due to pervasive illiteracy, and the demands for information for varied purposes, the Imo State Library Board redefined its information services to appeal to the auditory and visual senses of the illiterate and semi-literate groups. Durrani [13] has emphasized that for any information service to be sustainable, it should apply itself to the identifiable basic needs of the target elements, seek to foster two-way communication, and tailor its operations to align with information habits of their users rather than the modus operandi of traditional library or extension services.

In each of the eight rural community information centres within the Imo State Library System, the following activities and services are rendered within the limits of available funds:

(1) A demonstration farm, where sample crop varieties, fertilizer types, and methods of application are explained to local farmers.

(2) A display cabinet in which samples of improved varieties of crops and fertilizers are displayed.

(3) A billboard service. This is a skills and trade advertisement forum which affords rural dwellers the opportunity to create awareness of their respective skills, vocations, trades, or services.

(4) Film shows of approved documentaries on rural development initiatives.

(5) Repackaging and producing simplified guides to the propagation of crops such as yam, maize, soya beans, and plantain.

(6) Production of information leaflets and posters.

(7) Resource file maintenance. Each rural community information centre maintains a resource file, which is a tray that contains 3"x5" cards on which are recorded cross-indexed information on all services, programmes, organizations, institutions, and resources serving that community. The resource file is normally compiled and organized after conducting community surveys.

(8) Documentation of local culture and oral history. A bonafide community leader or elder is appointed who knows the culture and oral history of his community. His account is recorded on cassettes and preserved.

(9) Referral service. When a query cannot be readily answered by consulting the resources within the information centre, the inquirer is referred to other sources that can assist him.

(10) Translation of English language information materials into the vernacular, and subsequent tape-recordings of the same for the listening pleasure of the Igbo-speaking patrons. They usually troupe into the centres in the evenings, after the day’s chores, to attend the listening hour programme.

(11) The rural community information system renders direct and practical services in the form of letter writing completing of forms, etc.

(12) Advocacy services are rendered whereby the staff oblige the patrons by writing, speaking, or acting at their bequest in order to secure their entitlements.

(13) The system provides advisory and counseling services on the proper course of action to follow, especially when people come with complaints, as if the information centre were the statutory complaint bureau.

(14) Storytelling hours for the entertainment and socializing of children.

(15) Photographic and video documentation of traditional festivals.

(16) Display and exhibition of materials that are of rural development.

(17) Information service. Based on the analyzed information needs of the rural communities, information is provided to solve problems of everyday living having to do with housing, agriculture, health and medicine, recreation, transportation, occupation, etc.

(18) Fostering inter-agency cooperation and liaison. [14] This means nurturing mutual efforts by the wide range of change agencies towards achieving the goal of integrated rural development. The staff of the information centre strives to foster healthy cooperation by visiting change agencies; and obtaining their brochures, handbills, posters, and handbooks, which are used to build up resources for information reference services. Some times, particular agencies are invited to the centres to give talks and lectures about their organizational services as they affect the welfare of villagers. Experience has shown that this particular service plays an important role in achieving totally integrated rural development. There are many tasks to perform in this area. However, the Imo State Library Board is phasing out its operations because of financial and logistical constraints. Nevertheless, the potential dividends make it a worthy cause. These programs enable the library "to reach more people, improve services, maximize resources, extend services to previously unserved groups, develop more specialized services, avoid duplication of services, improve public relations, improve the library's image in the community, open up new possibilities for funding, increase support of the library by other agencies, and for the benefit of the community."

Breaking the Communication Barrier

In any typical rural community, whether in Nigeria or any other less-developed country where the literacy level is low, there is a barrier between the rural dwellers and the library. The rural dwellers are preoccupied with satisfying their families' basic needs, such as food, clothing, and shelter. For them, the library is strictly for the elite, and the rich members of society. Yet, they require information that would help solve problems of daily existence. Unfortunately, the existing library services were not tailored to suit their needs.

To dismantle this barrier, the Imo State Library Board carried out aggressive information sensitization crusades, which were mounted at the market and village squares, civic centres, school playgrounds, and recess arena within the communities. During such rallies, information counseling, film shows, symposia, and discussion groups were organized. The forums were used to distribute leaflets and simplified guides for crop propagation.

Reliable indigenous channels of communication were indentified, such as the paramount rule and his chiefs, title holders, opinion leaders, town criers, village heads, councilors, head teachers, and other influential citizens who, after their "conversion," joined in the sensitization crusade. Repeated announcements were made by the clergy in the churches.

The staff also organized community walks on a regular basis, during which they consorted with the rural dwellers in their homes, local beer parlours, at the village square, and other popular spots where they usually gathered in substantial numbers in the evenings, after the day's chores. It is pertinent to note that the timing of these visits was of paramount importance because the typical rural dweller can be very evasive when he is accosted at his farm, shop, marketplace, or at any moment when he is busy trying to earn a living. He does not welcome any kind of distraction when he is at work. He is more hospitable when he is at home.

The staff were encouraged to live among the communities to ensure availability and accessibility to the villagers whenever they desired. This was one of the shortcomings of some extension programs of the Ministries of Health and Agriculture, and the Directorate of Mass Mobilization for Social Justice, Economic Recovery, and Self-Reliance (MANSER). Their agents did not reside in the communities to monitor, obtain feedback, and consolidate on the gains of their service thrusts. When the staff lived among the villagers, a substantial degree of thrust developed, and they were allowed to attend meetings and gatherings of age groups, community associations, church councils, cooperative associations, community assemblies, etc., during which they gave talks and information counseling in the vernacular. The present tempo of the sensitization crusade should be vigorously maintained so as to consolidate the impact made so far.

Achievements

Rural community information service is a programme that requires a long period of time to mature. In spite of the numerous problems afflicting its implementation, the Imo State Library Board has been able to record modest achievements.

(1) The age-long barrier that had existed between the rural dwellers and the information system has been dismantled, especially in Orodo, in the Mbaitoli local government area. This is evident in the turnout of users to the centre for information or assistance. The sensitization programme has created immense awareness, and thus opened the eyes of many residents to the fact that the world does not end within the village boundaries, and that countless social and economic opportunities abound both within and beyond their communities.

(2) The novel, Things Fall Apart, by Chinua Achebe, has been translated into Igbo and subsequently recorded on audio cassettes for the listening benefit of Igbo-speaking patrons. Similarly, a good number of pamphlets received from MAMSER and the Directorate of Food, Roads, and Rural Infrastructures (DFRRI) have been translated into Igbo and tape-recorded.

(3) The rural community information services addressed the nagging question of the impact of the change agencies on the lives of the rural dwellers. Many of the villagers had referrals to the services of some of these delivery agencies, whose interests encompass not only agricultural practices, but also non-farming occupations and welfare-oriented issues.

(4) Another achievement is in the area of popularizing existing rural skills and technology, as people now freely come to advertise their skills and services on the billboard, which many acknowledged had helped to increase their incomes. Until recently, many people scarcely knew the extent of the skills, artisanry, and services within their communities.

(5) An Information Source Book for Rural Libraries and Information Centre Management in Africa, written by E. N. O. Adimorah, has been published by the Imo State Library Board, Owerri.

(6) Through substantial assistance from UNESCO and subsidy from the Imo State Library Board, a compuAdd 286 IBM compatible microcomputer with a hard disk drive, and a laser printer, were procured to create a computerized database on rural community information services. This computer has facilitated the production of The Orodo Rural Community Directory, and several copies of repackaged handouts on the propagation of selected crop varieties such as yam, maize, soya bean, banana and plantain suckers, and potato, which were distributed free of charge to users.

(7) The Orodo rural community information centre is being developed into a centre of excellence to serve as a model for the diffusion of rural community information services and management in the country. Recently, the Federal Ministry of Education and Youth Development, through the Nigerian National Commision for UNESCO, commissioned the Imo State Library Board to prepare a videotape documentary on the Orodo rural information centre. This is aimed at using Orodo as a model to provoke other public library boards in Nigeria to emulate. Two free copies of the documentary will be distributed to each public library board. This is a gesture in the right direction because the power of the videotape medium as an instrument of human development, according to Stuart, ". . . rests with its capacity to extend people's responsibility over their own lives by giving them direct access to the experience of others like themselves." [15]

Problems

The rural community information service is an innovative service in the public library movement in Nigeria, and indeed Africa. It is therefore faced with the following problems:

(1) The first, and certainly most constricting, is the tremendous cost of running such a programme effectively and efficiently in a cash-strapped economy, such as Nigeria is currently experiencing. The consists include funding for telecommunication facilities, television sets, video cameras and tape recorders; the cost of developing a computerized database; and the running cost of producing and changing posters, leaflets, and booklets; besides personnel and other overhead costs.

(2) Another difficulty encountered in fostering inter-agency cooperation and liaison. Many change agencies still perceive the rural community information centres as rivals, and hence are reluctant to cooperate. Some refuse to release their organizational brochures and other information documents that would enable the information centres to build reference and referral services, and give talks on issues that touch on the welfare of the masses.

(3) The location of a facility within a community generally determines the extent of its use by patrons. The Orodo rural community information centre in the Mbaitoli local government area, for example, is located in one extreme corner of a community of seven villages. Some patrons are compelled to visit the information centre only after other sources had failed to satisfy their needs.

(4) Another impediment is the re-orientation of staff to overcome the challenges posted by this new service outlet. The existing library schools in Nigeria have yet to incorporate rural information services in their curriculum.

Suggestions

(1) Availability of funds is the watershed from which many problems emanate. It also offers the parameter for measuring the efficiency and—to a reasonable extent—the effectiveness of service. The annual financial allocation to the Imo State Library Board is falling steadily. Public library service does not receive the state government’s priority attention because it does not generate a revenue. Therefore, the assistance of external funding agencies is solicited. A modest annual budget of N500,000.00 for each service center is considered appropriate.

(2) Better and improved inter-agency cooperation and liaison will be fostered through greater publicity of the services, improved public relations, and making them see how it helps them to accomplish their objectives.

(3) If there is to be unhindered access to the rural community information centre, it should be located at the community square, close to the central market, the recess arena, or at any place that accommodates large assemblies. This is to reinforce the principle of least effort, so that whenever a person has any need to visit the village square, or similar venue, he could at the same time walk across to the information centre.

(4) Existing library schools should be encouraged to review their curriculum to accommodate rural information services. In-house training programmes should be mounted on a regular basis to update the knowledge of the staff in this area.

The following courses have been recommended:

(1) Rural development

(2) Planning and organisation of rural libraries and information centres

(3) Rural sociology

(4) Organisation of rural information centres

(5) Information counseling and advocacy

(6) Rural information transfer channels and patterns

(7) Bibliographic control of rural information materials

(8) Rural library and information centre public relations

(9) Social welfare benefit law and practice

(10) Social administration

(11) Techniques of persuasion

(12) Communications—verbal and non-verbal

(13) Listening management

(14) Outreach and extension services

(15) Rural community analysis

(16) Market analysis and audience research

(17) Information needs, wants, demands, and uses

(18) Information storage and retrieval

(19) Change management

(20) Rural information services

(21) Information record keeping and repackaging

Conclusion

It is no longer a matter of conjecture as to whether the inhabitants of rural communities need information to help them make decisions to solve problems of daily living. The greatest challenge is to redefine the objectives of public library service and to fashion information products and services which fit the learning limitations of illiterates and semi-literates. The environmental and social characteristics of communities make them different from one another, and therefore influence the choice of economic activities, which in turn dictate the nature of information needs.

The cost of running such a service is very high. Governments must not deprive public libraries of the much-needed funds if totally integrated rural development is to be achieved. The world is fast becoming a global economic village. The assistance of international organizations is important to enable third world countries to stamp out illiteracy and to promote effective rural community information services which are vital in national development efforts.

The National Information and Documentation Centre (NIDOC) has undertaken as one of its projects the creation of centres of excellence at three rural community locations in Nigeria-Orodo, Badeku, and Birini-Kud in Imo State, Oyo State, and Jigawa State respectively. It would be highly appreciated if individuals or international funding agencies, interested in alleviating the information poverty of rural dwellers, could send financial assistance through UNESCO to NIDOC, to enable NIDOC to actualize this project.

References

[1] Wilkins, E., An Introduction to Sociology, 2nd ed. (London: Macdonald and Evans, 1976): 41.

[2] Anderson, R. G., Data Processing and Management Information Systems, 3rd ed. (Estover, Plymouth: Macdonald and Evans, 1979): 359.

[3] Erik de Man, W. H., conceptual Framework and Guidelines for Establishing Geographical Information Systems, (Preliminary Version). (Paris#58; General Information Programme and UNISIST, UNESCO, 1984): 10.

[4] Ogunsheye, F. A., "A Feasibility Study On Implication of Planning On Extension of Library Services to Non-Literates in Africa." Library Forum 1-1 (1982): 13.

[5] Opara, B. I., Information Needs In a Largely Non-Literate Community: A Case Study of Emii In Owerri Local Government Area, Imo State. Unpublished BLS thesis (Okigwe: Library Studies Unit, Imo State University, 1988): 60.

[6] Aboyade, B. O., op. cit.

[7] Adimorah, E. N. O. "Users and Their Information Needs In Nigeria: The Case of Imo State Public Libraries." Nigerian Libraries and Information Science Review 1 (1983): 137-48.

[8] Williams, S. K. T. "Sources of Information On Improved Farm Practices In Western Nigeria." Bulletin of Rural Economies and Sociology 4-1 (1969): 30.

[9] Aboyade, B. O. "Access to Information in Rural Nigeria." International Library Review (1985): 165-81.

[10] Aboyade, B. O., op. cit.

[11] Adimorah, E. N. O., "Information Needs of Change Agents: MAMSER, DFRRI, Agricultural Extension Officers, Etc." Paper Presented at the NATCOM-UNESCO National Seminar on Rural Library Development, Owerri, Nigeria, 27(29 Sept. 1987 : 14.

[12] Adimorah, E. N. O., "Coordination of Information Dissemination Activities at the Local Level" Paper Presented at the NATCOM-UNESCO National Seminar on Rural Library Development, Owerri, Nigeria, 27(29 Sept. 1987 : 8.

[13] Durrani, S., "Rural Development Information In Kenya." Information Development 1-1 (1985): 145-147.

[14] Weibel, K., Intra-Agency Cooperation In Expanding Library Services to Disadvantaged Adults (Madison, Wis.: School of Library Science, University of Wisconsin, 1975): 15.

[15] Stuart, S., "The Village video Network: Video As a Tool for Local Development and South-South Exchange." Convergence 20-2 (1987): 64.

[16] Adimorah, E. N. O., "Training for Rural Library and Community Information Centre Management." Education for Information 9-1 (1991): 55-59.

About the authors

E.N.O. Adimorah is Director, National Information and Documentation Centre (NIDOC), National Library of Nigeria, Lagos, Nigeria

Paschal Ugoji is Documentalist, Rural Community Information Systems Unit, National Information and Documentation Centre (NIDOC), National Library of Nigeria