A Cultural and Educational Link to the Homeland: Ethnic Minority Public Libraries in the Danish-German Border Region

Jeffrey W. Hancks

Abstract

For centuries ethnic Danes and Germans lived together peacefully in the independent Duchy of Schleswig. In 1864, Schleswig’s independence ended when it was formally incorporated into Prussia, a predominantly German-speaking nation. This also resulted in the creation of a large Danish minority in northern Schleswig. A final border revision in 1920 repatriated most ethnic Danes, but it also established a German minority in Denmark. Since then, both Denmark and Germany have provided robust cultural and educational programming and services, including libraries, to help preserve connections for ethnic Danes and Germans to their ancestral homeland. This paper provides an overview of Schleswig’s history prior to and immediately following the 1920 border revision. Its main focus, however, is on the comprehensive public library services provided to Schleswig’s ethnic Danes and Germans. The libraries are unique, and they play a vital role in educating Schleswig’s ethnic Danes and Germans about their ancestral homelands, while promoting civic engagement in their adopted countries.

Introduction

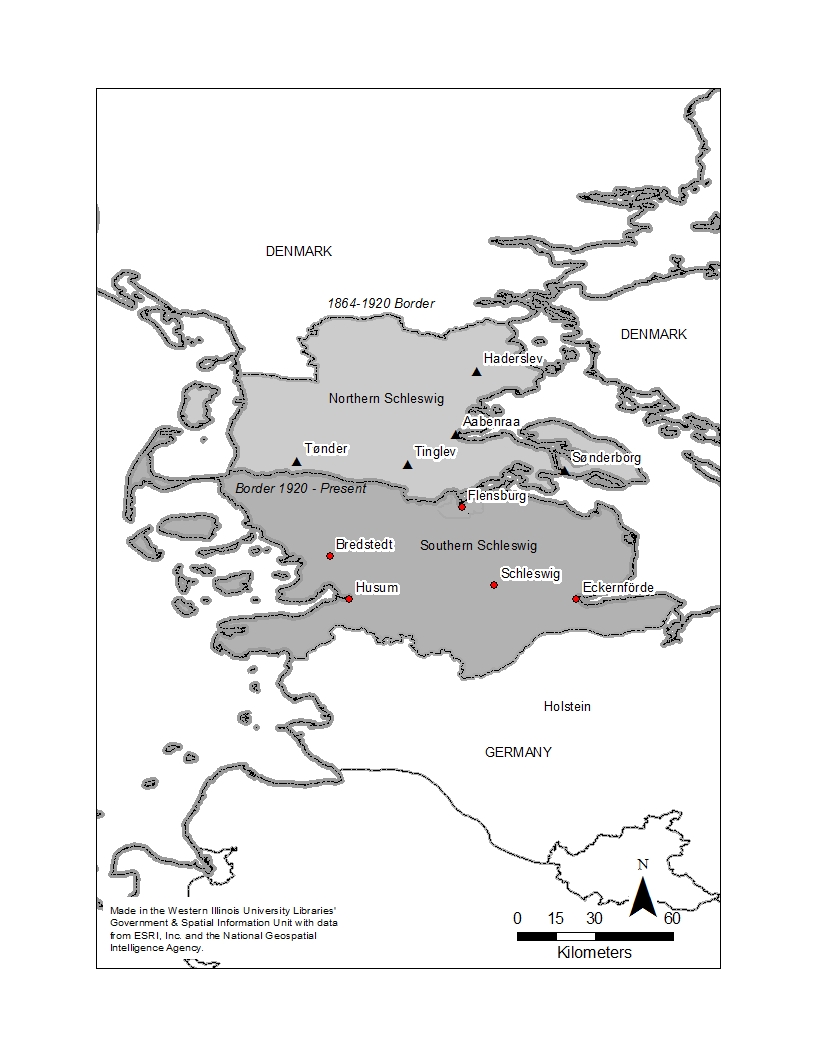

The theme of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions' (IFLA) 2010 Satellite Meeting in Copenhagen, Denmark was Libraries in a Multicultural Society – Possibilities for the Future. That Denmark was selected to host this specific meeting is not unusual, as the small Scandinavian nation has a long history of providing progressive library services to its minority populations.[1] While many of these services developed initially following an influx of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe and Turkey in the 1960s, Danish librarians have a century’s worth of experience providing comprehensive public library services for minority populations. The Danish Central Library for South Schleswig (DCLS), headquartered in Flensburg, Germany, and the Association of German Libraries in North Schleswig (AGLN), headquartered in Aabenraa, Denmark, exist to serve the informational and cultural needs of the approximately 50,000 ethnic Danes residing in northern Germany and the nearly15,000 ethnic Germans living in southern Denmark.[2] These institutions are some of the world’s best examples of how libraries can provide robust educational and cultural services that help national minority populations preserve their relationships to their ancestral homelands, while actively promoting citizenship and civic engagement in their adopted countries.

Historical Background of Schleswig-Holstein

To understand why ethnic minority populations exist in Schleswig and why they continue to receive support from their ancestral homelands, it is important to understand the region’s long history as the meeting place of German and Scandinavian culture. The former duchies of Schleswig and Holstein are located at a strategic crossroads on the narrow isthmus connecting continental Europe and Scandinavia. Consequently, there has long been considerable foreign interest in the area. For centuries, the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein were able to maintain a loose political affiliation with the Danish crown, while conducting extensive trade with the German-speaking territories to the south. This changed in 1848 when the Danish king announced his intention to integrate Schleswig fully into the Kingdom of Denmark , and thus sever the strong historical and cultural ties binding Schleswig to its southern neighbor, Holstein. The king’s actions infuriated German Confederation leaders, who viewed it as an overt act of aggression.[3] Ultimately, war broke out in 1848 between Denmark and the Schleswig-Holstein, Prussian, and German Confederation armies, resulting in a Danish victory in 1851.[4] The peace was tenuous, however, and in 1864 a second Schleswig-Holstein war broke out. This conflict ended catastrophically for Denmark, forcing the king to cede his claim to all of Schleswig-Holstein to the German Confederation.[5]

Suddenly, nearly 200,000 ethnic Danes living in Schleswig were separated from Denmark.[6] Shortly after the transfer, the German Confederation began implementing various rules and regulations aimed at bolstering German nationalism in Schleswig, even going so far as to make it illegal for Danes to use their language and celebrate their culture. Danish was never lost as a daily language in northern Schleswig, but the language and culture were certainly threatened by the repeated German governmental efforts to Germanize all of Schleswig by restricting contact to Denmark and pushing the German language and culture on all residents of Schleswig.[7] Not surprisingly, North Schleswig accounted for the highest rate of Danish immigration to the United States. Between 1868 and 1900 and estimated 59,400 people, or about 40 percent of the county’s population, emigrated.[8] Daily life for North Schleswig’s Danes settled down after 1900 until the outbreak of World War I. Germany’s defeat in that war, despite Denmark’s neutrality, posed a unique opportunity for the Danish government to push for a solution to what had become known as the Schleswig Question.[9]

Following the war, Article 109 of the Treaty of Versailles called for the people of Schleswig to determine their national affiliation. Schleswig was divided into two zones, and residents went to the polls in each zone to vote to either unite with Denmark or to remain part of Germany. In February 1920, voters in Zone One, consisting of the northernmost part of Schleswig from the 1864 border to a line near the Flensburg Fjord and running west to the North Sea, voted by a three to one majority to reunite with Denmark. The following month voters in central Schleswig’s Zone Two, consisting of the city and district of Flensburg plus the districts of Leck and Niebüll and the North Sea islands of Sylt and Föhr, voted by a three to one majority to remain part of Germany. On June 15, 1920, all of the territory in Zone One was returned to Danish sovereignty, while the entirety of Zone Two remained German territory.[10] King Christian X of Denmark and Danish Prime Minister Niels Neergaard participated in reunification celebrations in North Schleswig on July 10-11, 1920. Speaking at a ceremony at historic Dybbøl Hill near Sønderborg on July 11, Neergaard assured the ethnic Danes living south of the new border, saying, “A bitter pain, despite all the joy, fills our minds for those who have fought so faithfully. On behalf of the government and the Danish people I say ‘they will not be forgotten.‘ It is an honor-driven duty for each government to support them and to the utmost ability maintain the language and national affiliation for which they have bravely sacrificed.”[11] Neergard summarized well most Danes’ feelings. They were simultaneously ecstatic that North Schleswigers were reunited with Denmark and terribly disappointed that thousands of South Schleswigers were not coming home. His words offered hope to those left behind that Denmark would provide the assistance and support South Schleswigers' needed to maintain their cultural links to Denmark.[12]

|

| Figure 1:Schleswig Map |

Danish Reaction to the 1920 Reunification

After the border revision, an estimated 20,000 ethnic Danes remained in South Schleswig. Many of them lived in or around South Schleswig’s largest city, Flensburg, but ethnic Danes were found scattered throughout the region.[13] Keeping the prime minister and king’s solemn promise to remember them became an important point in Danish foreign policy for the next several generations. Danish community leaders and government officials determined that an ideal way to demonstrate to South Schleswig’s ethnic Danes that they were indeed remembered was to offer them many of the same social services that were available to Danish citizens north of the border. Efforts began almost immediately to build a service network among the ethnic Danes, and the results were impressive. Despite their successes and a continued interest in promoting Denmark in South Schleswig, when given the opportunity to annex the remainder of Schleswig following Germany’s World War II defeat, the Danish government asked that the border remain as it was following the 1920 partition—its significant Danish minority notwithstanding. The region remained largely German in ethnicity, and the Danish government preferred to restrict its efforts to individuals who felt a true connection to Denmark.[14]

Following the War, Danish minority leaders expanded the work of the Border Association ( Grænseforeningen), the umbrella organization charged with supporting the minority’s activities. Funded by the Danish government, the Border Association further developed its network of Danish language daycare centers, kindergartens, elementary and secondary schools, sports clubs, churches, health care centers, youth and senior citizen centers, cultural centers, public libraries, and other services to provide ethnic Danes with social, educational, recreational, and spiritual services in the Danish language.

Establishing and building these cultural institutions was time consuming and expensive. While the post-war years did not see German government attempts to limit the ethnic Danes' rights and activities, Border Association leaders wanted to see laws enacted to protect their investments. In 1955, the governments of Germany and Denmark ratified the Bonn-Copenhagen Declarations and accomplished precisely that goal. The treaty guaranteed both ethnic Danes and Germans in Schleswig the freedom to associate as national minority members, establish schools, speak and write their language, and realize a host of additional rights and responsibilities.[15] The freedom of association, wherein members can freely identify with and subsequently disassociate as an ethnic minority member, is cherished in Schleswig. Thusly, no official census of the minority populations exists. In Schleswig, the policy is known colloquially as Minderheit ist, wer will (the minority is who wants it), and it protects citizens from fear of retribution caused by national affiliation.[16]

German Reaction to the 1920 Reunification

Upon the transfer of Zone One to Danish sovereignty, approximately 15,000 ethnic Germans found themselves living in Denmark. Many were frustrated with the way the plebiscites were organized, and they were not interested in adapting to life as a national minority population. In fact, many viewed the rise of Adolf Hitler and National Socialism and the subsequent German invasion of Denmark in April 1940 as paths to an eventual full reunification with Germany. Demonstrating their loyalty to Germany, over 750 German-minded North Schleswigers died fighting for the Third Reich. After the war, 3,500 German North Schleswigers were arrested for cooperating with the German occupation of Denmark, and all of the German minority’s properties were seized. Upon the establishment of the Association of North Schleswig Germans ( Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger) in 1945, life and social conditions for the German minority improved. Two of the Association’s first acts were releasing a statement that it accepted the 1920 border as permanent and swearing an official declaration of loyalty to the Danish constitution.[17]

Setting up the infrastructure to provide for the German minority’s needs was left to the Association of North Schleswig Germans. Like the Danes in South Schleswig, the Germans in North Schleswig established a comprehensive network of youth services including daycare centers, kindergartens, and elementary and secondary schools. Social service agencies assisted the elderly and coordinated free time and recreational services for youth and families. Furthermore, German culture and history was celebrated via religious organizations, choirs, theaters, museums, and a research institute. Additionally, a German language public library system provided books, media, and public programming designed to educate and entertain users.

Danish Library Services in South Schleswig

Danish leaders determined quickly that establishing a public library was an essential part of the overall plan for nurturing an ethnic minority population in South Schleswig. Naturally, a facility was required. To meet this need, The Border Association acquired Flensborghus, an historic Danish building used previously as an orphanage and later a barracks. From the beginning Flensborghus was planned as much more than a book repository, and it was quickly transformed into a public library and cultural center, stocked primarily with materials donated from Denmark.[18] Library administrators understood from the start that the Danish library in South Schleswig needed to play a leading role in hosting lectures and other events designed to engage their patrons with Danish history and culture. Flensborghus accomplished that.

Danish library services in South Schelswig grew throughout the 1920s, and services continued mostly unimpeded after the National Socialism takeover in the early to mid1930s. The outbreak of the Second World War did, however, have a direct impact on Danish library services in South Schleswig. Books, magazines, and other materials sent from Denmark were subject to censure by Nazi officials, and books already on library shelves were also subject to removal. The Danish minority and its institutions did not suffer great hardship because Adolf Hitler considered Danes a Germanic people. Consequently, they received a privileged status within the Third Reich and the library’s cultural programming continued throughout the war.[19]

Following the war, the population of South Schleswig exploded with refugees from other parts of Germany. Many of these new residents noticed Denmark’s wealth and stability compared to Germany’s desperate situation, and they aligned themselves with the Danish minority. This caused problems for library management, who felt obligated to provide services to the new arrivals, most of whom had no prior connection to either Schleswig or Denmark. As Germany’s economy improved these people gradually left the Danish minority, and the library was able to return to its focus to its long-established patron base.[20]

Danish library services in South Schleswig took a giant leap forward in 1959. That year the library was renamed the Danish Central Library for South Schleswig ( Dansk Centralbibliotek for Sydslesvig), and it expanded into a regional central library serving all of South Schleswig. Library leaders envisioned their facility becoming much more than what was offered at Flensborghus. They wanted to create a comprehensive cultural center for ethnic Danes across the entire region. What they built was a showplace of mid-century Danish and Scandinavian design. With its bright, open concept stacks and public service areas, modern furniture and fixtures, numerous meeting rooms, and ample exhibition space for artists, the facility quickly became the gold standard for public library design for the next generation throughout Denmark and much of Germany. The new structure ushered in an exciting era in the DCLS’s history, setting it on course for providing modern public library services to the region’s residents.

Today, the DCLS operates much like its municipal public library counterparts in Denmark with a main library, branches, and a whole host of services offered to patrons. The system has five locations situated throughout South Schleswig. The main library is centrally located in downtown Flensburg. Branch libraries are located in the cities of Schleswig and Eckernförde in southeastern South Schleswig and Husum and Bredstedt in western South Schleswig. Public library services such as book and film circulation, reference assistance, computer and Internet access, and meeting space are standard at DCLS.

What makes this public library system so unique is the high level of engagement it has with its patrons. The DCLS is highly conscious of its special responsibility to promote knowledge and appreciation of Danish and Nordic culture among its users. To that end, it schedules a wide spectrum of classes, workshops, study circles, and other educational opportunities which give participants rich opportunities to connect with, and relate to, their Danish and Nordic heritage. Hosting Danish language, history, and cultural studies classes and making available a large collection of language instruction materials are essential library activities. While a system of approximately fifty Danish elementary and secondary schools serve children and help keep the Danish language vibrant in South Schleswig, the library focuses its efforts on adult education. These lifelong learning opportunities fit well with the Nordic tradition of folkeoplysning, or popular enlightenment, and contribute positively to building an enlightened, engaged national minority population. The library is also home to one of eight Nordic Information Offices (NIO) located throughout the Nordic region. Sponsored by the Nordic Council, an intergovernmental forum created by the Nordic national governments, the NIO sponsors guest lecturers, art exhibitions, concerts, and other entertaining events to educate the public about the Nordic countries.

For patrons who cannot come to the library, DCLS has bookmobile and postal mail programs. Two vehicles crisscross South Schleswig, making regular stops at dozens of schools, daycare and senior citizen centers, and even at private homes to provide books and multimedia materials to residents. Colorful Danish and Nordic motifs are painted on the bookmobiles, and they are a highly visible sign of the DCLS’s commitment to providing library services to ethnic Danes throughout South Schleswig. Recently the bookmobile added a stop in Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein’s capital and largest city, giving the library an increased presence there. The postal mail program extends the DCLS’s services to users in other parts of Germany. Once a week materials from the DCLS’s circulating collection are sent out to users, free of charge. The service also includes materials from Denmark and the other Nordic countries in the Nordic languages (Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish, Icelandic, Faeroese, Sámi, and Greenlandic) as well as books in other languages about life and conditions in the Nordic region.

Two of the library’s most well-known resources are its local history collection and its research archive. The Schleswig Collection has become a preeminent regional history repository, with a special mission to collect materials telling the story of the Danish minority in Germany. Housing over 50,000 items, including books, newspapers, and pamphlets documenting the history of all of Schleswig, it is used regularly by a wide range of researchers, from casual history buffs to school children to professional historians.

The research archive employs a team of professional historians and archivists who collect manuscripts, photographs, posters, maps, films, and sound recordings documenting the Danish and North Frisian minorities in South Schleswig. They also publish extensively. To date, the research department has produced over eighty scholarly publications, covering a broad range of topics important that explore the unique history of South Schleswig and its residents.

The current situation of the DCLS appears strong. In 2011, the library operated on a €3.75 million budget, with nearly 87 percent of its funding coming from the Danish government and ten percent from the German government. In 2013, forty-eight employees, including fourteen librarians, staff the library’s system of five libraries and two bookmobiles. The combined gate count for the libraries exceeded 106,000 patrons, and nearly 600,000 items circulated. Formal Danish language library services are approaching their centennial celebration in South Schleswig, and it is evident that they have become an integral part of the Danish minority’s link to Denmark.[21]

German Library Services in North Schleswig

Ethnic Germans also have a long history of targeted library services in North Schleswig. Shortly after the 1920 plebiscite, ethnic Germans in Denmark established German language libraries in schools and in private homes. The libraries operated effectively and by the end of World War II ninety German-language libraries were scattered across North Schleswig.[22] Anti-German sentiments were understandably high after the war, and German-minded Danes were often singled out and persecuted for their perceived anti-Danish sentiments. After Denmark’s liberation in 1945, nearly 3,000 ethnic Germans were arrested for cooperating with the occupation. Furthermore, a majority of the German library personnel were arrested, and library facilities were seized.[23] About 25 to 30 percent of the 70,000 pre-war books on the shelves were destroyed as part of the de-Nazification process.[24]

Eventually time began to heal post-war wounds, and by 1949 cooler heads began to prevail. Ethnic Germans decided to build their own independent library system, i.e. the Association of German Libraries in North Schleswig (AGLN) ( Verband Deutscher Büchereien Nordschleswig). German libraries opened in the North Schleswig cities of Aabenraa, Haderslev, Sønderborg, and Tønder. To serve rural residents, a German-language bookmobile began traversing North Schleswig’s roads in 1967, with a second vehicle added in1972. In 1991, a fifth library branch opened in Tinglev, the North Schleswig city with the highest number of ethnic Germans.

Much like the DCLS, the German libraries provide their users with more than just books, periodicals, and audiovisual materials. They also create opportunities for ethnic Germans to interact, socialize, and celebrate their shared German culture via public programming that features guest lectures, puppet theater shows, literature festivals, musical performances, and youth activities. A unique resource available to patrons of the main German library in Aabenraa is the Artothek collection. Designed to foster an interest in art and artists, the North Schleswig Artothek contains nearly 800 prints and paintings by artists from Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein which may be borrowed by regional institutions and residents.

The AGLN maintains a special commitment to preserving the German minority’s history. The North Schleswig Collection houses books, non-published materials, films, oral histories, and other materials documing the region’s mixed Danish and German history. The library is digitizing its North Schleswig Collection materials with the goal of making them accessible to remote users online. The German library also maintains an online encyclopedia, in the form of a wiki, at www.nordschleswigwiki.info, to provide up-to-date information about the German minority’s history, its influential members, and its current activities.

As of 2012, the five libraries and two bookmobiles remained in service and employed a staff of twenty-one, including eleven librarians.[25] Fifteen additional libraries were supported by the AGLN in regional German schools. Library holdings totaled approximately 230,000 items, and the libraries' 8,000 patrons circulated 350,000 items. The AGLN’s annual budget was just over ten million Danish kroner, with the German federal government and the German State (Bundesland) of Schleswig-Holstein collectively contributing two-thirds and the Danish government paying one-third.[26]

Reflections from Library Users

Public libraries exist to serve their users. Successful libraries provide services reflecting the values and needs of their constituents. This is no different in specialized institutions like Schleswig’s ethnic minority libraries. With the support and assistance of the current directors of the Danish and German libraries, patrons from both libraries offered their views on their local libraries and how the libraries may adjust to the needs of their respective minority communities in the future.

Serving adult patrons has long been a primary focus of the Danish libraries. Retired teacher Signe Andersen, 65, from Hattstedt used the Danish library system since the nearby Husum branch opened in 1954 (personal communication, August 1, 2013). She praised the wide variety of cultural programming and activities available to her at the main library in Flensburg and the other branch locations. She noted that Germany does not have the same tradition as Denmark for using public libraries as cultural centers, and she appreciates the opportunity to learn about Danish culture at the library. According to Andersen, libraries staffed with Danish speakers afford her and other members of the minority an opportunity to speak Danish on a regular basis. She believes having opportunities to speak the language regularly are critical to maintaining Danish as a language of daily communication in South Schleswig. Signe Andersen’s husband, Anders Schaltz Andersen, 70, is a native Dane who moved to South Schleswig in 1970 to assume a teaching position at the Danish school in Husum (personal communication, August 2, 2013). He used the library for teaching materials, and now in retirement he uses the library to conduct research occasionally. Schaltz Andersen is especially interested in the Danish libraries providing services to children and youth, as he believes they are essential to their development as members of the minority. Kay von Eitzen, 46, is the janitor at Oksevejens Danish Elementary School in Flensburg (personal communication, August 18, 2013). Von Eitzen grew up in a family with connections on both sides of the border, and he used the Danish libraries since he first went to school in 1973. Using the library was a natural part of his everyday life, and to this day, he has never visited the much larger German public library in Flensburg. Von Eitzen did not use the library much as a young man, but as an adult he considers himself a regular patron. He noted it is especially important to have access to Danish music, films, and newspapers, as they are difficult to find in the majority German society. According to von Eitzen, the Danish minority without its own library system is “unimaginable”.

Minority families with school-aged children also reap benefits from utilizing their local minority library. Cordula Rohrmoser, 35, and her husband Thomas Bindslev Rohrmoser, 42, view the Danish libraries as an invaluable service for their family’s research and educational needs (personal communication, November 6, 2013). The family moved to Schleswig in 2008, and they immediately became library patrons. Rohrmoser is originally from Cologne, Germany, and Bindslev Rohrmoser is from Copenhagen. Rohrmoser uses the library for her academic research in Scandinavian Studies, and Bindslev Rohrmoser uses the library to supplement his work as a Danish teacher at the local Danish high school. The couple’s four children, ranging in age from two to twelve years, are also regular library users for picture books, nursery rhymes and homework assistance. Rohrmoser wishes the local Schleswig branch were larger and provided more children’s programming, but she is very grateful for the library and what it offers. She hopes the Danish libraries remain strong for years to come, because she contends that Danish life in South Schleswig is “impossible” without them.

Paula Bonnichsen, 73, from Bylderup-Bov has used North Schleswig’s German libraries, both the public libraries and the school libraries, all of her life (personal communication, November 8, 2013). She considers the libraries an important linguistic lifeline for the German minority. Bonnichsen also enjoys the lectures and meetings held at the libraries. She noted the opportunities for local artists to display their works are especially important to the minority community. Henriette Hindrichsen, 43, is a commercial manager from Sommersted (personal communication, November 8, 2013). She used the bookmobile regularly as a child. Now that she has children, she requested the bookmobile stop at her home so her kids can have the same experience. The doorstep service is important to Hindrichsen, because her family lives on a farm 23 kilometers from the closest German library. She sees the German libraries as a critical service to the minority as it helps them keep the German language alive in North Schleswig. According to Hindrichsen, the German language is a vital part of the minority’s identity.

Anja Metzdorf, 43, her husband Hans David, 54, and their two children Boi Metzdorf David, 5, and Kilian Metzdorf David, 11, from Gejlå, near Padborg, are also regular library users (personal communication, November 8, 2013). Metzdorf prefers reading books in German, and the library allows her to do this. David is a farmer, and he uses the library to keep current on agricultural developments in Germany. Boi attends the German kindergarten in Padborg and Kilian attends the German school in Padborg. The German library helps them with language and social development. Metzdorf noted that the bookmobile service is especially important to her family. She is unable to drive a car, and the doorstep service makes it possible for her and her children to borrow materials. Edda Metzen, 71, from Aabenraa is a long-term German library user. Previously she visited the German school libraries and used the bookmobile, but in recent years she visits the main German library in Aabenraa (personal communication, November 8, 2013). In addition to checking out books and media, she also enjoys the art exhibits, concerts, lectures, and dramatic performances held at the library. All participants hope the German libraries will continue long into the future, but they recognize that economic conditions may require the libraries to consolidate or join forces with the majority Danish libraries. Twin sisters Anika Maria Stange and Maike Johanne Stange, 18, are students living in Aabenraa (personal communication, November 9, 2013 and November 11, 2013). They enjoyed visiting the bookmobile when it came to their childhood home, but now as high school students living near the main German library, they prefer to go there. They both agree that the German libraries are an important resource for the minority population, but they are unsure what their future holds. Maike Johanne Stange posits that libraries in general are threatened by the Internet and society’s turning away from a reading culture. She is confident, however, that the German minority will remain vital in North Schleswig, and that there will also be at least one large library serving them. Anika Maria Stange feels that the small rural libraries may not exist in the future because of what she calls “North Schleswig abandonment.” German-minded North Schleswigers must leave the area to pursue a higher education in that language. According to her, once they leave, few return to work and raise families.

Conclusion

Comprehensive information about ethnic minority library services in Schleswig is available only to researchers able to read both German and Danish and, as a consequence, the story is virtually unknown to library professionals and scholars outside of Germany and Scandinavia. This article informs English-reading researchers about the rich library services available to the 65,000 Danish and German ethnic minorities residing in Schleswig; however, it is by no means complete. Much remains untold about the origins of library services in the region, the Nazi influence on minority libraries, library services to the region’s North Frisian minority community, and the future for the ethnic minority libraries in the digital age. A study comparing and contrasting ethnic minority library services in Schleswig to efforts in other countries would also be a valuable contribution to the literature.

The Danish and German minorities in Schleswig occupy a unique place among the world’s ethnic minority public libraries. The work to build an infrastructure conducive to nurturing ethnic minority populations has paid tremendous dividends in Schleswig. For generations historians referred to the region’s national affiliation and future viability with the dubious monicker “the Schleswig Question.” Today, there is no question. The border has been settled for almost one hundred years. The Danes of South Schleswig and Germans of North Schleswig are active, respected citizens in their respective countries' democracies. They are also engaged in the preservation of their cultural heritage. There is no doubt that the substantial governmental financial support the ethnic Danes and Germans receive facilitates the operation of the many services, including public library systems, that make it easier to maintain close ties to their homelands. Ultimately, however, it is the peoples' desire to maintain those connections and their freedom to do so without fear of retribution that makes Schleswig’s ethnic Danes and Germans an enviable model for peacefully integrating national minority populations.

Endnotes

1 Ågot Birger, “Recent Trends in Library Services for Ethnic Minorities – the Danish Experience,” Library Management 23, nos. 1-2 (2002): 79.

2 In many cases Schleswig’s cities have different names in the Danish and German languages, with no universally-accepted English-language translation. Therefore, this paper employs city names of the current majority language. For example, cities located in present-day Germany are identified by their German-language name, and cities located in present-day Denmark are identified by their Danish-language name.

3 William Carr. Schleswig-Holstein 1815-1848: A Study in National Conflict (Manchester, England: Manchester University Press), 265-92.

4 W. Glyn Jones. Nations of the Modern World: Denmark (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970), 53-54.

5 Ibid., 56-57.

6 Bent Rying. Denmark in the South and the North, Vol. 2 (Copenhagen: Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1981), 294.

7 Ibid., 296.

8 Kristian Hvidt. Danes Go West: A Book About the Emigration to America. (Rebild, Denmark: Rebild National Park Society, Inc.), 129.

9 Rying, Denmark in the South and the North, 327.

10 Ibid., 328-32.

11 Danmarkshistorien Encyclopedia, s.v. “Statsminister Niels Neergards (V) Genforeningstale På Dybbøl,” http://danmarkshistorien.dk/leksikon-og-kilder/vis/materiale/statsminister-niels-neergaards-v-genforeningstale-paa-dybboel-1920 (accessed 27 February 2013).

12 For more English-language information about Schleswig-Holstein history and the 1920 reunification see Lawrence Dinkerspiel Steffel. The Schleswig-Holstein Question. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1932), Sarah Wambaugh. Plebiscites Since the World War. (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for World Peace, 1933), Peter Thaler. Of Mind and Matter: The Duality of National Identity in the German-Danish Borderlands. (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2009), Jørgen Kühl. The Schleswig Experience: The National Minorities in the Danish-German Border Area. (Aabenraa, Denmark: Institut for Grænseregionsforskning, 1998), and Lorenz Rerup, “National Minorities in South Jutland/Schleswig,” in Ethnicity and Nation Building in the Nordic World, ed. Sven Tägil (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995), 247-81.

13 Jørgen Kühl, “The National Minorities in the Danish-German Borderlands,” in Living Together: The Minorities in the German-Danish Border Regions, eds. Andrea Teebken and Eva Maria Christiansen (Flensburg, Germany: European Centre for Minority Issues, 2001), 11-24.

14 Rying, Denmark in the South and the North, 332.

15 European Center for Minority Rights. “The Bonn-Copenhagen Declarations,” http://www.ecmi.de/about/history/german-danish-border-region/bonn-copenhagen-declarations/. Accessed February 28, 2012.

16 Jørgen Kühl. The National Minorties in the Danish-German Border Region. The Case of the Germans in Sønderjylland/Denmark and the Danes in Schleswig-Holstein/Germany. (Aabenraa, Denmark: The Danish Institute of Border Region Studies, 2003), 17.

17 Peter Thaler, “A Tale of Three Communities: National Identification in the German-Danish Borderlands,” Scandinavian Journal of History 32, no. 2 (2007): 152-53.

18 Lars N. Henningsen and Jørgen Hamre. Dansk Biblioteksvirke i Sydslesvig: 1841-1991. (Flensburg, Germany: Dansk Centralbibliotek for Sydslesvig, 1991), 45. This Danish-language volume is the authoritative history of Danish library services in South Schleswig.

19 Lars N. Henningsen. Sydslesvigs Danske Historie. (Flensburg, Germany: Dansk Centralbibliotek for Sydslesvig, 2009), 140.

20 Thaler, A Tale of Three Communities, 153-54.

21 Information about the Danish Central Library for South Schleswig’s current services, activities, and statistics was taken from the Danish-language version of the library’s website at http://www.dcbib.dk/. Accessed 28 February 2013.

22 Nis-Edwin List-Petersen. Mehr Als Bücher: 60 Jahre Bibliotheksarbeit in Nordschleswig Festschrift zum 60. Jubiläum der Gründung des Verbandes Deutscher Büchereien Nordschleswig. (Aabenraa: Verband Deutscher Büchereien Nordschleswig, 2009), 8. This German-language festschrift is the most comprehensive history of German library services in North Schleswig.

23 Nordschleswig and the German Minority in Denmark. (Aabenraa, Denmark: Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger, 2010), 6-7.

24 List-Petersen, Mehr Als Bücher, 8-9.

25 Information about the Association of German Libraries in North Schleswig’s current services and activities was taken from the German- and Danish- language versions of the library’s website at: http://www.buecherei.dk/index.php/de/ and http://www.buecherei.dk/index.php/dk/. Accessed February 28, 2013.

26 “Finanzierung” and “Ausstattung,” North Schleswig Wiki, http://www.nordschleswigwiki.info/index.php?title=Deutsche_B%C3%BCchereizentrale_und_Zentralb%C3%BCcherei_Apenrade. Accessed February 28, 2013.

References

Berger, Ågot. “Recent Trends in Library Services for Ethnic Minorities – the Danish Experience,” Library Management 23, nos. 1-2 (2002): 79-87.

Carr, William. Schleswig-Holstein 1815-1848: A Study in National Conflict. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1963.

Henningsen, Lars N. Sydslesvigs Danske Historie. Flensburg, Germany: Dansk Centralbibliotek for Sydslesvig, 2009.

Henningsen, Lars N., and Jørgen Hamre. Dansk Biblioteksvirke i Sydslesvig: 1841-1991. Flensburg, Germany: Dansk Centralbibliotek for Sydslesvig, 1991.

**Hvidt, Kristian. Danes Go West: A Book About the Emigration to America. Rebild, Denmark: Rebild National Park Society, Inc., 1976.

Jones, W. Glyn. Nations of the Modern World: Denmark. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970.

Kühl, Jørgen. “The National Minorities in the Danish-German Borderlands.” In Living Together: The Minorities in the German-Danish Border Region, edited by Andrea Teebken and Eva Maria Christiansen, 11-24. Flensburg, Germany: European Centre for Minority Issues, 2001.

Kühl, Jørgen. The National Minorties in the Danish-German Border Region. The Case of the Germans in Sønderjylland/Denmark and the Danes in Schleswig-Holstein/Germany. Aabenraa, Denmark: The Danish institute of Border Region Studies, 2003.

List-Petersen, Nis-Edwin. Mehr Als Bücher: 60 Jahre Bibliotheksarbeit in Nordschleswig. Festschrift zum 60. Jubiläum der Gründung des Verbandes Deutscher Büchereien Nordschleswig. Aabenraa, Denmark: Verband Deutscher Büchereien Nordschleswig, 2009.

Nordschleswig and the German Minority in Denmark. Aabenraa, Denmark: Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger, 2010

Rying, Bent. Denmark in the North and the South , Vol. 2. Copenhagen: Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1981.

Thaler, Peter. “A Tale of Three Communities: National Identification in the German-Danish Borderlands.” Scandinavian Journal of History 32, no. 2 (2007): 141-166.

About the author

Jeffrey Hancks is the Baxter-Snyder Professor of Regional and Icarian Studies at Western Illinois University Libraries where he coordinates the Archives and Special Collections Unit. He is also the founding editor of the forthcoming book series "Celebrating the Peoples of Illinois" at Southern Illinois University Press. He holds an EdD in Adult and Community Education from Northern Illinois University, and MA Degrees in Scandinavian Studies and Library and Information Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research interests include rural librarianship and Illinois ethnic studies.

Contact Email: JL-Hancks [at] wiu [dot] edu