Library Trends in Uzbekistan

Claudia V. Weston

Abstract

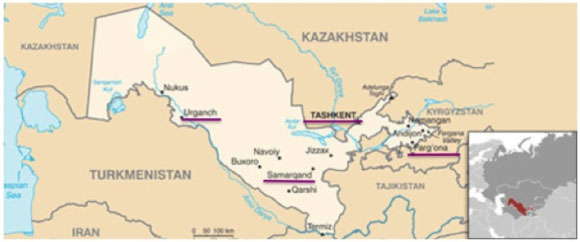

In October 2011, the author had the privilege of conducting a series of seminars for librarians in Uzbekistan as a speaker for the U.S. Department of State’s U.S. Speaker and Specialist Program. This paper documents some of the observations made during the question and answer sessions of the presentations, meetings with library directors and administrators, and tours of the libraries in Tashkent, Samarkand, Urgench, and Ferghana.

Introduction

In October 2011, the author had the privilege of conducting a series of seminars for librarians in Uzbekistan as a speaker for the U.S. Department of State’s (DOS) U.S. Speaker and Specialist Program. The DOS, Bureau of International Information Programs, Office of U.S. Speakers solicits program requests from U.S. embassies throughout the world, provides funding, and coordinates aspects of the program that are not in–country (such as arranging air travel to and from the United States), obtaining visas, and processing payment for honoraria and travel expenses. The in–country embassy coordinates all other activities such as organizing the speaker’s itinerary, fine–tuning seminar topics, working with local organizations to host the presentations/seminars, arranging in–country travel, making hotel accommodations, etc. The bureau and the embassy jointly select the speaker that fulfills the needs of the particular program.

According to the original program request from the American Embassy in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, (Lauterbach, e–mail message, 2011) the genesis of this particular program came from the Government of Uzbekistan (GOU) who requested technical assistance in the formation of electronic catalogs, creating information resources, and improving qualifications. These three areas became the topical themes of the seminars. Ample time was scheduled for discussions during and after each session.

Uzbekistan

Located in Central Asia and about the size of California, the country of Uzbekistan evolved through a series of mergers of independent territories and khanates. In 1924, it became a republic of the Soviet Union and on September 1, 1991, after the Soviet Union dissolved, it became an independent nation. Although Uzbekistan is the most populous Central Asian country with about twenty–eight million people, it continues to be fairly rural with a significant percentage (28.2 percent) of the population depending on farming — particularly cotton production — and forestry for its livelihood. Much of the infrastructure put into place during the Soviet rule has undergone some form of change. A transition in the spoken language is one example of the changes taking place in this country (Background Note: Uzbekistan, June 30, 2011).

|

| Figure 1: Map of Uzbekistan adapted from the USAID Web site (http://centralasia.usaid.gov/node/393). The cities where presentations were held are underlined — Taskhkent, Samarqand (Samarkand), Urganch (Urgench), and Fargona (Ferghana). |

During the Soviet Era, Russian was the state language for the entire Soviet Union including Uzbekistan. School–age children studied Russian as their primary language. The status of Russian as the primary language began eroding in 1989, when Uzbek joined Russian as one of the official languages in Uzbekistan. In 1995, Russian lost its official language status, leaving Uzbek as the official language. This movement led to a notable decrease in the number of Russian–Uzbek language schools from 1,147 in 1992 to 813 in 2000 (Yunus, 2006). In 2003, it was estimated that only 57 percent of the population could still speak or understand at least some Russian. More school–age children spoke and studied Uzbek as their primary language, and studied languages such as English or German as their secondary languages. Library signage, instruction, and collections reflect this language diversity.

Presentations

The U.S. Speaker and Specialist Program sponsored presentations in Tashkent, Samarkand, Urgench and Ferghana. Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, serves as the hub for government, industry and trade, and the library and information community. The GOU expended significant resources to design and construct a new state–of–the–art national library in Tashkent to showcase the nation’s information resources, provide a modern space for study and research, and host symposia and workshops. The new national library building held its grand opening in December 2011.

Samarkand, Urgench and Ferghana are homes to regional information library centers. Just as the Ferghana Regional Information Library Center named after Akhmad al Fragoniy serves as a resource for over 114 resource centers in Ferghana, so do the Regional Information Library Centers in Samarkand and Urgench serve as resources for library and information centers in the Samarqand and Khorezm provinces, respectively. With over 70 percent of the population in the Fergana, Samarqand and Khorezm provinces living in rural areas, the advisory and mentoring role of the regional information library centers is critical to the dissemination of new technologies, standards, processes and procedures.

The presentations held in Tashkent, Samarkand, Urgench and Ferghana focused on the creation of electronic catalogs, particularly shared catalogs, and the development of digital libraries. Having heard that the skill and knowledge level of those in attendance would be varied, the presentations began with basic information and then gradually built on the foundation established. Emphasis was placed on the underlying objectives of catalogs; models for shared catalogs; and the relationship between metadata and system objectives. More specific talking points included:

- The benefits of electronic catalogs over print catalogs

- The benefits of shared catalogs

- The diversity of online catalog systems and digital archives — some created by libraries, others by organizations such as the Internet Archive

- OCLC and other large shared bibliographic systems

- Concepts behind resource sharing

- Techniques and questionnaires to aid in planning digital initiatives

On a more practical note, the author distributed numerous handouts for use in planning for and undertaking digitization projects. Because many of the participants, particularly those from rural areas, have limited Internet access, some of the handouts contained Web–based resources that had been printed out. Others such as the Best Practice Guidelines for Digital Collections at University of Maryland Libraries, second edition (2007) were translated, with permission, into Russian prior to dissemination. The author also encouraged participants to either contact her directly or through the embassy in Tashkent. Business cards were distributed at each library session.

|

| Figure 2: Author lecturing on digital libraries and e–catalogs, photo courtesy of Daniyar Salihov, U.S. DOS. |

On Saturday, October 8, 2011, the first in the series of presentations was held in Tashkent and attended by twenty–seven library administrators, instructors, and other practitioners. The attendees appeared very comfortable with the subject matter and shared information on the development of the Uzbek national catalog, the digitization of their library collections, and the use of electronic information resources by their institutions. There was great interest in OCLC as a resource for bibliographic records and OCLC as catalog. One of the attendees, an instructor for library and information science, expressed interest in obtaining OCLC training accounts in order to provide her students with hands–on experience in identifying, selecting, and editing bibliographic records in a shared catalog environment.

The second in the series of presentations was held in Samarkand on Monday, October 10, 2011 at the Samarkand Regional Information and Library Center named after Pushkin. In a meeting before the presentation, Shakhodat Akhmedova, the director of the center, gave an overview of the center and the region it serves. She described the center’s ongoing digitization, professional development, and electronic catalog projects and its efforts to overcome very limited resources. Following the meeting, forty–eight center staff members and library directors from throughout the region attended the presentation. A comment on the usefulness of centralized electronic catalogs for resource sharing prompted a larger discussion of inter–library lending, a practice not common within the rural information resource centers of Uzbekistan.

The third presentation was held on Tuesday, October 11, 2011 in Urgench and, following the pattern established in Samarkand, was preceded by a meeting with Elmira Rashidovna, the deputy director of the Information and Library Center of the Khorezm Region. Thirty–four regional library administrators and center staff were in attendance. One of the most memorable conversations after the presentation focused on a discussion of the routine use of electronic databases and journals by academic faculty, and the rare and exceptional use of these resources by students.

|

| Figure 3: Cotton! Uzbekistan is the fourth largest producer of cotton in the world. |

The final presentation was held on October 13, 2011, in the newly renovated Ferghana Regional Information–Library Center named after Akhmad al Fragoniy to an audience of sixty–two center staff and library administrators from the Ferghana Region and its surrounds. According to Diloram Shukurova, the center director, the governor of the region had recently provided the center with funding to renovate the front of the building, buy books and computers, replace the book lift, replace the air handling system, and complete a number of other projects that had been on the center’s list. The governor’s rationale was that any service that drew the attention of the youth the way the library does should be funded. At the end of the day, the center director said that most of her staff could understand and learn from the presentation, but for others it reminded her of her trip to the United States, wherein when she saw the new technology she thought it was make believe, a fairy tale. She thought many of the other information resource center directors likewise felt as though what was being presented was a fairy tale.

Libraries in Uzbekistan — Background

All libraries in Uzbekistan, known either as “information resource centers” or “information and library centers”, report to the Government of Uzbekistan. Prior to 1996, all information centers fell organizationally under the Ministry for Culture; in 1996 academic information centers moved under the Ministry for Higher and Secondary Special Education, school information centers under the Ministry for Public Education, and the fourteen regional Information and Library Center (regional ILC) under the Uzbek Agency of Communication and Information. The regional ILC serves as a resource for information resource centers and libraries located throughout its respective region. Of the fifteen thousand libraries in Uzbekistan, about seven thousand of them are public libraries (Rakhmatullaev, 2002). Although directors, administrators, and select staff from academic and special information resource centers were represented at the seminars, particularly in Tashkent, the majority of the seminar attendees were from the regional ILCs and the populations they serve. Most of the observations in this paper relate to this particular library community.

In the proceedings of Central Asia 99, Marat Rakhmatullaev (Rakhmatullaev, 2000) reported that a “new theme in the development of libraries in Uzbekistan is the creation of virtual automated libraries.” He defined a virtual library as one that is “equipped with computers and information equipment for fast access and transfer of information ... that distributes information by modern methods ... [and that] will provide business journalists, economists and reviewers with information about events occurring in the country and abroad, and with news of social and economic life.” He went on to say that:

In order to meet these priorities, collaborative efforts will focus on several activities:

|

In 2002, these areas continued to be a priority. The Central Asia — 2002 conference (Rivkah, 2003) focused on “Internet and libraries: information resources in science, culture, education and business” with the sessions clustered into the following subthemes:

- Promote an effective exchange of information regarding the creation of library systems, the use of Internet and the development of electronic information resources for science, education, culture and business in libraries;

- Organize and exploit training centers for the teaching of new information technologies;

- Create virtual libraries and corporate networks; and

- Improve and increase activities of libraries regarding the wider use of the Internet and electronic databases by providing open access to existing and newly created information resources.

Stumbling blocks to accomplishing these goals were identified as the lack of a national strategy for integrating piecemeal assistance from international and foreign organizations into a cohesive national plan, the lack of national strategy for the support of an information and education infrastructure, the high cost of licensed databases, the high cost of Internet access, and a telecommunications infrastructure that does not satisfy the constantly growing demands of education, research and development, or any others (Rakhmatullaev, 2002). Despite these stumbling blocks, the regional ILCs and other information and library networks share information on advances in information technology and library practice and work toward refreshing and upgrading the skills of the information and library community. Progress also has been made on the development of national union catalog (Umarov, 2004).

Libraries in Uzbekistan — Where they are today

The activities identified during the Central Asia 99 conference for creating a virtual automated library in Uzbekistan serve as useful benchmarks for assessing where Uzbek libraries are today. To recap, these activities were:

- Training — creation of frequent training courses;

- Internet connectivity — creation of a telecommunication environment;

- Coordinated cataloging — coordination and cooperation during cataloging;

- Internet resources — access to global information resources through the Internet;

- National information resources, electronic catalog — creation of national information resources.

Training

Improving the qualifications of library personnel through workshops, seminars, conferences, and study abroad opportunities continues to be a priority for Uzbekistan. Guest lecturers from throughout the world are invited to speak on topics of current interest in a variety of forums. Two notable examples include

- a seminar entitled the “Innovation in library affairs. Paper and electronic paper: competitors or supplement?” held in Samarkand on December 14, 2011 and cohosted by the Russian Center for Science and Culture in Tashkent in cooperation with Samarkand Union of Russian Language and Literature Teachers and Samarkand Regional Information–Library Center named after Pushkin,

- and an international conference “Towards the Knowledge Society: New Roles for Librarians in a Changing World” held in Tashkent and Samarkand, Uzbekistan, October 10–14, 2011 (http://www.eifl.net/news/eifl-uzbekistan-plays-key-role-international-) and organized by EIFL (EIFL) — an international not–for–profit organization that works with libraries to enable access to digital information in developing and transition countries (EIFL Web site: http://www.eifl.net/who-we-are), Tashkent University of Information Technologies, and the Tashkent Institute of Culture.

The U.S. Embassy American Speaker Program is another such example.

As mentioned earlier, the regional ILC serves as a resource for information resource centers and libraries located throughout its respective regions. Conducting training sessions is an important aspect to fulfilling this role. In 2010, for instance, the Samarkand Regional Information and Library Center named after Pushkin offered five large seminars with over two hundred in attendance, four round tables, four presentations, three practice sessions, and twenty–eight information/library product and/or process reviews to the 314 Information Resource Centers located in colleges and lycees, and throughout the national education system. These sessions were held in addition to consulting with individual institutions on technical and procedural issues. The other regional ILCs provide similar services to their regions (Samarkand, 2011?).

Not surprisingly, librarians in the larger cities have greater exposure to current information techniques and technologies than those who live in the rural areas. More than once, participants commented that the further away from the city one traveled, the less robust the Internet connection. Transportation costs and limited Internet access continue to have a significant impact on the amount of information that can be found and shared. Most of the training material shared by the regional ILCs with the library and information resource centers they serve is disseminated on paper, CD–ROM, or DVD.

Internet connectivity

Tatjana Lorković noted in her report on the Issykkul’ 2007 library conference, that “one of the issues, rarely talked about, but present in the minds of many participants, was the necessity of technical support for Internet availability in small libraries in Central Asia. These libraries have experienced slow response times for their Internet systems which are also prone to intermittent collapses” (Lorković, 2009). This continues to be the case for information centers throughout Uzbekistan with very limited for–fee patron access to the Internet through information centers in the larger cities.

Coordinated cataloging

Despite the ubiquity of OCLC in western libraries, very few librarians in Uzbekistan knew about OCLC and the services it provides. OCLC plays a significant role in facilitating resource sharing worldwide as well as serving as a source for bibliographic records. At the regional ILCs visited, there was no evidence that they planned on using OCLC or any other database as a source of records for their local catalogs. Each regional ILC hosts its own system and creates its own bibliographic records, thereby absorbing the full cost of original cataloging for each item added to their electronic catalogs.

Given the non–collaborative nature of local catalog creation, it is noteworthy that the National Library of Uzbekistan has an agreement with the Russian State Library to use the Russian State Library’s catalog as a source for bibliographic records. The National Library predicts that a large portion of the four million records from the Russian State Library will match its holdings due to the common source of their respective collections. It is envisioned that this project will greatly expedite the retrospective conversion of a significant portion of the paper shelf list but an equally significant portion remains to be converted as time and staffing permit.

All the libraries visited use IRBIS as their electronic catalog system. IRBIS is an integrated library system developed by the Moscow State Public Scientific Technical Library and is found in libraries throughout Russia and the CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) countries. An Uzbek library system, KaDaTa, is under development and is being trialed in some of the regional ILCs. Once the KaDaTa system is in production, it is envisioned that all regional ILCs will migrate to this new system.

Internet resources

As is the case with training, the use of Internet resources for research and teaching is greatly dependent on the information center’s proximity to large cities and the availability of reliable, high–speed Internet connections. The regional ILCs visited rely heavily on print reference resources for day–to–day reference queries; very few routinely use electronic resources. Those information centers that make electronic databases available for use by their patrons frequently charge for the service.

Uzbek libraries are able to license access to electronic databases, e.g., EBSCO databases, through EIFL. In addition to these resources, the Urgench State University (UrSU) named after Al Khorezmi negotiated access to the digital dissertation database of the Russian State Library. Researchers, scholars, and faculty are the primary users of these licensed electronic resources. Factors limiting the use of Internet–based electronic resources were identified as the language of the resource, poor Internet connectivity, and lack of Boolean search expertise.

Each of the regional ILCs visited has digitized items from its special and/or rare book collections. The digitized copies, stored as JPEG files on a local server, are available through links from bibliographic records in the electronic catalogs of those centers. Due to system constraints, however, many of the ILCs’ catalogs are not Internet–accessible and neither are the digital files of the scanned items. The catalogs and the digitized resources are accessible only within the library building. Interestingly, one of the most requested services through the Ferghana Regional Information–Library Center named after Akhmad al Fragoniy Ask–a–Librarian service is for access to electronic versions of traditional Uzbek literature. This is a good indication that there is a growing demand for electronic information by Uzbek citizens.

National information resources, electronic catalog

As of the first quarter 2011, the national union catalog had grown to contain 497,000 bibliographic records. It is the intent of the Government of Uzbekistan that the national union catalog reflects the comprehensive holdings of all libraries in Uzbekistan. The catalog has grown significantly since the 150,000 records it held in 2004, but much work is still needed to capture records that reflect a combined general collection of 4,936,000 items (Government of Uzbekistan, 2011?; Umarov, 2004?). Also, it is unclear whether this national union catalog is or will be publicly Internet–accessible since, as of this writing, the author has not been able to access it.

Although the internal procedures for adding records to the union catalog varies from one library to another, the process used by the Samarkand Regional Information and Library Center named after Pushkin is similar to those described by the other centers. A record is first input into the local catalog, then a separate unit reviews the record and rekeys the required elements into the national catalog. There is no copy cataloging, exporting/importing single records from one system to another, or batch loading records from one system to another. The Ferghana Regional Information and Library Center named after Akhmad al Fragoniy, however, seemed to have been able to create a process for uploading a subset of records that matched the format required by the KaDaTa system without rekeying. The process as described takes an enormous amount of effort for the individual centers not only in creating original catalog records for each of their titles for their local systems, but in keying and re–keying records and in performing quality control for two separate bibliographic systems.

Additional Observations

Physical collections continue to be of great importance to the information centers of Uzbekistan. In addition to designated circulating collections, each regional ILC holds special collections for in–house or in–collection use only. According to Uzbek law, the regional ILCs are required to keep all publications that are given to them and as a result of this law, some are experiencing significant storage issues.

Despite limited funding for the maintenance of library facilities and the provision of library service, the regional ILCs have shown great creativity in designing new spaces and implementing new programs. In Samarkand, the regional ILC fashioned a space for children equipped with small desks and age–appropriate reading material. This space was established after the director had come to the United States and been inspired by similar spaces in U.S. libraries. In Urgench, the Khorezm Regional Library created a small museum dedicated to the culture and history of Khorezm. This museum houses exhibits of traditional dress, ceramics, and cloth and has created multimedia DVDs on books and topics of regional interest. In Ferghana, the Regional ILC’s fine and performing arts collection features different exhibits by local artists while the Foreign Language Collection hosts a weekly study group drawing as many as fifty to sixty people at a time to discuss predetermined themes and topics. The librarians encountered were proud of their collections and the services they were able to provide.

Conclusion

After attending the Central Asia 2002 conference in Bukhara, Uzbekistan, Frank Rivkah observed that the “level of sophistication among the Uzbek librarians is impressive” (Rivkah, 2003). Not only is their level of sophistication impressive but so is their creativity and drive. Despite the challenges they face, they seek opportunities to offer new and innovative services while working to create a national digital presence.

Through the U.S. Speaker and Specialist Program, Uzbek librarians from urban and rural institutions were able to see glimpses of the potential for electronic catalogs and digital libraries provided through screen shots of a variety of systems. Paper translations of the Best Practice Guidelines for Digital Collections at University of Maryland Libraries, second edition (2007) and other handouts were left with the librarians for use as a resource when they were ready to move forward on their projects. It is the author’s hope that the librarians in attendance also saw a brief glimpse into the life of a medium–sized academic library in the United States.

This visit served as a healthy reminder that different cultures view their libraries in different ways and that not all libraries share the same level of technological development. Although this seems obvious, it is easy to forget when dealing with the day–to–day at one’s own institution. We’ll end by recounting a conversation with Daniyar Salihov, IRC Director, Public Affairs Section, U.S. Embassy, Tashkent, Uzbekistan on one of our lengthy drives from one location to another. During this conversation, he mentioned that most Uzbeks access the Internet through handheld devices. Given the early stages of library automation witnessed in the libraries visited, you wonder how this factor alone will impact the evolution of library technology in Uzbekistan.

Acknowledgments

The author owes a special thanks to Daniyar Salihov, IRC Director, Public Affairs Section, U.S. Embassy, Tashkent, Uzbekistan and those with whom he coordinated the sessions. Without their attention to detail, willingness to answer naive questions, and knowledge of the Uzbek library community, the author could not have learned as much as she did. Any errors, misunderstandings, or misinterpretations in this document are hers and not theirs.

Resources

Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs. “Background note: Uzbekistan’ U.S. Dept. of State. June 20, 2011 http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2924.htm (accessed January 4, 2012)

Government of Uzbekistan. “Review of ICT development in Uzbekistan.’ Governmental Portal of the Republic of Uzbekistan. 2011? http://www.gov.uz/en/helpinfo/network_informatization/2671 (accessed January 4, 2012)

Steven Lauterbach, e–mail message to author, May 27, 2011.

Lorković, Tatjana. “Central Asian librarians strive to achieve a unified library network and stronger cooperation among their libraries. CALINET is planned for the future.” Yale University Library Slavic And East European Collection. Yale University Library. 2009. http://www.library.yale.edu/slavic/docs/issykkulconference/ (accessed November 22, 2011).

Rakhmatullaev, Marat A. “Advanced information library infrastructure: as an important social tool for the prevention of crisis situations in Central Asia.” Library Hi Tech News. 19, no. 9 (2002). (Emerald).

Rakhmatullaev, Marat A. “‘Central Asia 99’: Results and Perspectives.” Library Hi Tech News. 17, no. 4 (2000). (Emerald).

Rivkah, Frank. “Central Asia 2002 — International library conference, in Bukhara Uzbekistan.” Library Hi Tech News. 20 no. 1 (2003). (Emerald).

Samarkand Regional Informational Library Centre by name of A. S. Pushkin. “The Centre today.” Samarkand Regional Informational Library Centre by Name of A. S. Pushkin. 2011? http://samarkand.infolib.uz/en/today.html (retrieved January 4, 2012).

Umarov, Absalom. “Uzbekistan: the National Library of Uzbekistan: annual report to CDnl 2003–2004.” Conference of Directors of National Libraries (CDNL). 2004. http://www.cdnl.info/2004/uzbekistan.rtf (retrieved November 1, 2011).

Yunus, Khalikov. “Uzbekistans Russian–Language Conundrum.” EurasiaNet.org. 2006. http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/insight/articles/eav091906.shtml (retrieved November 17, 2011).

About the author

Claudia Weston is the Government Information Librarian at Portland State University Library located in Portland, Oregon. Prior to arriving in Portland, she held various administrative and technical positions at the National Agricultural Library.

E–mail: westonc [at] pdx [dot] edu

© 2013 Claudia Weston.