On Being Open: The Real Meaning of Open Access, Open Content, and Open Source

The Inaugural Follett Lecture, Graduate School of Library and Information Science,

Dominican University, 2 February 2005

Edward J. Valauskas

Abstract

This paper describes notions of openness: open source, open courseware, open access publishing, and other efforts to make digital information more accessible. It notes the growing global interest and support for open projects by individuals, governments, foundations, and corporations. The paper closes with a proposal for an international center dedicated to educating individuals about open source and open access projects.

Introduction

I thank the Follett family for their generosity to Dominican University and the Graduate School of Library and Information Science. It has been a distinct pleasure for me to be part of this great University and to work with so many inspiring students and faculty.

The Dean describes me on occasion as the alpha and omega of the School because I teach a wide variety of classes. My wife describes me not as a chair, but as satee. I teach classes entitled “History of the Printed Book,” “Reference Sources in the Sciences,” “Information Policy,” “Internet Fundamentals and Design,” and “Internet Publishing”. You might wonder how all of these classes relate. I hope by the end of this talk you will understand.

Let me begin.

How many of you know Thursday Next? (see Figure 1)

|

| Figure 1: Miss Thurday Next from Jasper Fforde’s series of Thursday Next novels. Source: http://www.geekmom.com/tag/thursday-next/. |

Thursday is one of my favorite fictional characters, the star of Jasper Fforde’s novels with the delicious titles of The Eyre Affair, Lost in a Good Book, The Well of Lost Plots, and Something Rotten [1]. Thursday has the remarkable ability to open a book and literally become a part of it. She becomes part of the plot, interacts with characters and scenes, and makes a point about the dangers of becoming immersed in The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe. For me, Thursday Next has opened up a whole collection of novels that have long gathered dust in my imagination — in ways that I had not thought possible.

That is the essence of what the current open movement is doing. Like thousands of Thursday Nexts, participants in open source are opening computer programs in new and exciting ways. Researchers, librarians, publishers, and members of professional societies are all armies of Thursdays creating new ways of thinking about dusty scholarly journals with open access and open content. Educators are diving into their classes, revitalizing their syllabi with open course ware.

A definition of openness

What do I mean by open? Open activities have a lot in common. First, and foremost, to quote Larry Sanger, the founder of the Web–based encyclopedia Wikipedia, “you have to have faith in human beings being able to work together.” [2] If you are not familiar with Wikipedia, I will describe it in more detail later in this talk. Thanks to the Internet, thousands of individuals participate in a variety of open projects, from creating an encyclopedia such as Wikipedia to putting together a new Web browser to collecting papers for a different kind of Internet magazine. This collective action makes all of the different open projects incredibly powerful. All open projects take advantage of the Internet to communicate, to collaborate, and to transform ideas into new digital products. All open projects make their work accessible to all freely — and by free I do not mean “free as in free beer, but free as in freedom” [3]. Free to examine, criticize, correct, and revise, returning something new to all.

Patterns of openness

Open projects organize in a variety of ways, but there are some basic patterns that emerge in these efforts.

Consider the onion (see Figure 2).

|

| Figure 2: The onion, sliced. Source: http://globetrotteren.wordpress.com/2011/05/06/how-helpless-do-we-want-to-be-perceived-as/. |

Like an onion, all open projects have layers [4] (see Figure 3). In the center you will find the creators or initiators, those individuals that had a great idea, or solved a problem that needed to be fixed. Around those inventors, you find a small group of experts who take a given concept and develop it, who take error reports and make changes, who deal with all of the conversations about the implementation of a great idea and improve upon it. Finally there are the users, who test a digital product in a variety of conditions that could never be replicated in a laboratory. They report bugs and problems, and suggest ways to make the implementation of a great idea even better. Projects succeed where communications are rich across all these groups, where work is inclusive, not exclusive, where kings and queens, worker bees, and drones, all work and communicate together.

|

| Figure 3: The onion, as a model for openness. Source: Crowston and Howison, Figure 1 (2005). |

Alan Cox, one of Linus Torvalds’ Linux colleagues, relates the story of one programming group where a communications breakdown killed the project. The “inner circle” set up kill files, or bozo filters, to stop all messages from those they perceived as “dangerously half–clued people with opinions.” [5]

Unfortunately for the project, the “dangerously half–clued” actually had many good ideas about future directions for programming. They also saw a lot of bugs. The project, with its bozo filters, defied one of the basic laws of openness. “Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow,” so goes Linus’ Law [6], and so the bugs are squashed. The project died a painful death. Alan Cox described the effort as “one of the world’s most pointless exercises.”

Let me give you another example. SquirrelMail is a Web–based e–mail reader with a great tag line — “Webmail for nuts” [7]. It is an open source project with many programmers and users, all working to improve SquirrelMail. SquirrelMail has versions in a number of languages, including Arabic, Basque, Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Icelandic, Japanese, Lithuanian, two flavors of Norwegian, Polish, two flavors of Portuguese — for Brazil and for Portugal, Romanian, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, Thai, Turkish, Ukrainian, and — naturally — Welsh. As you might imagine, there are a lot of conversations online to develop SquirrelMail.

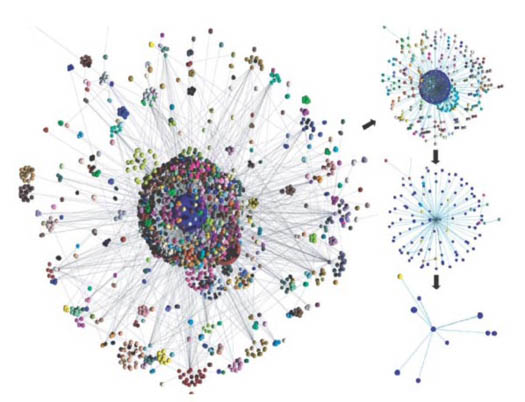

Figure 4 is a social network analysis of thousands of SquirrelMail bug reports, taken from a paper that appeared in First Monday [8]. This illustration shows the reality of the “onion”, with communication between an inner core of developers and programmers and an outer core of users, all working to make SqurrelMail better, and dare we say, nuttier.

|

| Figure 4: Plot of interactions for SquirrelMail. Source: Crowston and Howison, Figure 10 (2005). |

The way in which SquirrelMail works is a microcosm of the way in which the World Wide Web works.

A paper published in Nature examined more than 325,000 Web pages connected to each other by at least one hyperlink [9]. There is an interesting pattern that emerges, not too different from the patterns that we have seen so far (see Figure 5).

|

| Figure 5: A view of a complex network called the World Wide Web. Source: Song, Havlin and Makse, Figure 1b (2005). |

We are only beginning to understand the underlying complexity of interactions between individuals and digital information. Let’s look at some examples of openness resulting from these social networks.

Examples of openness

The Directory of Open Access Journals at Lund University in Sweden records a little over 6,700 open journals containing over 596,300 articles [10]. Most of these digital journals started in the last five to ten years.

Many of you know that I am familiar with one of the journals noted in this Directory, entitled First Monday (see Figure 6). First Monday had its origins in a variety of meetings in the early 1990s of the Working Group on Intellectual Property Rights, part of the National Information Infrastructure Task Force established by then–President Clinton. I was one of several representatives for libraries to the Working Group. We were trying to figure out the best ways to make publishing work with the then new public medium of the Internet. Many representatives at the meetings of the Working Group thought that the Internet should be tightly controlled. Some of the most vocal were representatives of commercial publishers of scholarly journals. I wondered out loud at the meetings why a scholarly journal couldn’t take advantage of the Internet and be successful. I didn’t get far with my ideas in those meetings of the Working Group. Finally, in 1995, I had a chance to test my notion with a Danish publisher, Munksgaard. Munksgaard was interested in exploring the Internet as a publishing medium – but was not ready to risk one of its own significant scholarly titles. My notion of a journal would give Munksgaard some experience with this digital medium.

|

| Figure 6: Opening page of First Monday, circa January 2005. Source: First Monday, at http://firstmonday.org. |

First Monday was launched in May 1996 as an Internet–only, peer–review, monthly journal, publishing research about the Internet. By the end of 1998, Munksgaard decided that it had learned all it could learn from the experiment, and sold First Monday to me and two fellow editors — Esther Dyson and Rishab Ghosh. We moved the contents of the journal’s server from Copenhagen to Chicago and the Library at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

First Monday has been, and remains, quite a remarkable adventure in open access and open content. In its virtual pages, 1,119 papers have been published in 179 issues written by 1,437 different authors representing institutions in over thirty countries [11]. The content of the journal has been examined by readers in over 180 countries. Papers from First Monday have been recycled in stories and columns in the New York Times, Washington Post, Business Week, and numerous other newspapers and magazines around the world. Contributors remark that their papers in First Monday have more readers and commentators than any other published work. Clifford Lynch, author of several papers in First Monday and Executive Director of the Coalition for Networked Information, calls First Monday a “phenomenon.” It is a phenomenon because it is open and freely accessible.

What is the impact of the open movement on teaching in higher education?

OpenCourseWare is a direct response to the for–profit higher education business, labeled by David Noble in a paper in First Monday, “digital diploma mills” [12]. Initially funded by the Hewlett Foundation, as well as many other organizations and individuals, there are literally thousands of courses available online as OpenCourseWare [13]. MIT alone (http://ocw.mit.edu/index.htm) has 2,000 open courses available online (see Figure 7).

|

| Figure 7: Open page of MITOpenCourseWare. Source: MITOpenCourseWare, at http://ocw.mit.edu/index.htm. |

To say that OpenCourseWare is wildly successful would be an understatement. The wide ranging educational effects of online courses are immeasureable. In fact, some commerical “diploma mills” see OpenCourseWare as their major competitor in the higher education market.

A student might say, “I have a choice between free and openly accessible materials from some of the most significant institutions in the country on one hand, and thousands of dollars emptied from my wallet to a market–based “diploma mill” — with a doubtful pedigree — on the other. What will I do?” Indeed, I think diploma mills have something to worry about — as challenges to their business plans emerge.

What’s happening on the programming front?

The Open Source movement in software emerged in the 1990s largely thanks to Linux. In 1990, the software business was largely proprietary and exclusionary — with Microsoft clearly dominating over Unix and offerings from Apple. A decade later, Linux — and its many “open source–inspired” programming children — were giving Microsoft a fright. Corporations such as IBM and Sun, among others, are providing vast resources to support open source. Open source seems to growing in momentum, with programs springing up literally by the thousands. At last count, SourceForge, a free open source development site, registered over 260,000 open source projects, involving nearly three million individuals around the world [14]. Clearly, Linus Torvalds, the originator of Linux, started something that’s changed the way programmers work and interact [15].

All of these remarks so far may make it seem that the entire open movement is a relatively recent development, inspired by technology. Certainly the Internet is the engine behind the current open movement. Nevertheless, the open movement has a distinct scholarly and academic spin, where bugs are not disastrous problems but fascinating intellectual exercises. The scholarly roots of the modern open movement are long and deep. Let me give you a few examples.

A history of openness

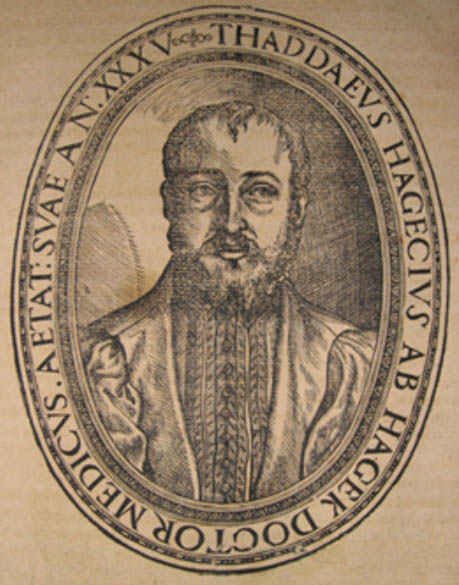

Let’s take a look at one of my favorite sixteenth–century scientists, Thaddeus Hajek, or Thaddaeus Hagecius, who lived from 1525 to 1600 [16]. He worked largely in Prague and wore many hats — as the private physician to Emperor Rudolf II, mathematician, geographer, meteorologist, alchemist, astronomer, and botanist. In the dictionary next to the word “polymath” there should be a portrait of Hajek.

|

| Figure 8: Thaddeus Hajek (1525–1600). Source: Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Herbarz. Prague, 1562. Lenhardt Library, Chicago Botanic Garden. |

I know Hajek best as a botanist because he translated Pietro Andrea Mattioli’s herbal into Czech. Mattioli’s herbal was a sixteenth–century best seller, with tens of thousands of copies printed in various editions and translations. Mattioli (1501–1577) was certainly a friend of Hajek — because Mattioli was a physician for a time to Rudolf II’s father, Maximilian II [17]. Hajek’s translation was published in Prague in 1562; there is a nice copy of this work, with many fascinating annotations, in the Lenhardt Library of the Chicago Botanic Garden.

I probably would like to have known Hajek better in his role as a beer maker; Hajek was the author of the first printed book on beer making which appeared in 1585.

Hajek corresponded with all of the leading luminaries of science in Europe of the time, openly sharing his discoveries. He used his influence with Rudolf II to actually encourage the Emperor to invite scientists to visit — and stay — in Prague. Hajek’s efforts were successful — because he openly shared his ideas and discoveries with his colleagues.

Hajek is best known for his careful observations of a supernova exploding in the constellation Cassiopeia in 1572 and the Great Comet in 1577. He freely shared his data with astronomers, such as Tycho Brahe in Denmark.

Brahe immediately recognized the significance of Hajek’s very modern approach to science. Brahe moved to Prague as Imperial Mathematician — now isn’t that a great title? — where he designed astronomical instruments, and in Hajek’s footsteps made many observations — creating a catalog of a thousand stars. Brahe had the good sense to hire one Johann Kepler as a calculator. Kepler in turn used Brahe’s data to develop a basic understanding of the principles governing planetary motion.

Prague would not have been the European center for science that it was in the absence of this spirit of openness — of sharing observations, of scholarly conversations attempting to solve the thorny scientific problems of the time. Certainly the support of Rudolf II helped — but the underlying catalyst that made Prague the Los Alamos of its day was a spirit of openness, of collective scientific activity towards common goals.

Let me provide you with a more recent example of the roots of openness.

Many years ago when I was in high school and college, I had the good fortune to work for the curator of fossil invertebrates at the Field Museum, Gene Richardson. Gene is best known for his work on fossils from the Mazon Creek area, some fifty miles south of here around Braidwood and Coal City. Hundreds of weekend paleontologists collected fossils from the coal strip mines in the area, along with students like me. The three–hundred–million–year–old fossil fauna of the area is amazing because many soft–bodied organisms were preserved. Fossil shrimp, jellyfish, sharks, insects, worms, scallops, horseshoe crabs, and other creatures were found. But the strangest was an animal that Gene named Tullimonstrum. A marine invertebrate, there never has been a creature quite like it, ever [18].

It is now the state fossil of Illinois [19].

Gene had access to collections with hundreds of thousands of specimens. One census indicated that at least 230,000 fossils were collected over a period of several decades. Gene could have decided to hoard all of this material for his own, describing these fossils over time, with his name attached to each and every taxonomic elaboration. Instead, Gene openly shared this unique fauna with paleontologists around the world. He sought out the best experts to describe these amazing discoveries. In doing so, he accelerated the description of these ancient extinct animals by decades — for paleontology is not a fast business. His commitment to openness allows us to contemplate a very different prehistoric Illinois.

An open future

I’ve examined a little about the meaning of openness, provided some examples, and looked at the scholarly roots of these notions of open.

Where can we find openness? Literally everywhere. Here are a few examples.

On the Web, 60 percent of the servers providing all of us information run Apache — that is, an open source, Web server program [20].

If you use Google, its hundreds of thousands of servers use Linux [21]. At least 48 percent of America’s corporations use open source software in one way or another in their operations [22].

Increasingly, major computing companies are supporting openness at a variety of levels. For example, IBM has has more than 600 developers working on more than 100 open source efforts [23]. IBM has made freely available some 500 patents, governing everything from encryption to digital storage. IBM has called on other corporations to create a “patent commons” for open source — to develop a common ground for collaboration [24].

OpenSolaris is an open source project initially started by Sun Microsystems with current support provided by Oracle. It involves thousands of people working worldwide operating on laptops, desktop computers, and servers. OpenSolaris has its historical roots in Unix, a version developed by Sun and AT&T [25].

Why are corporations rushing to open source? They see future profits in providing services to users of openly accessible programs. In a sense, this future is already happening. At IBM, fourth quarter revenues for 2010 saw increases in both software (by 11 percent) and services (by two percent) [26], with record profits for the year. Making software openly available means increased revenues — by providing specialized services to assist in the management of those openly accessible programs. Open source is big business.

Let’s return to Wikipedia, an open publishing project. Wikipedia is the most popular, openly accessible encyclopedia in the world. It includes over nineteen million articles, organized and written by thousands of Wikipedians, creating versions in 281 different languages [27]. Dynamic, new and revised entries are added constantly. Just for comparison, Encyclopaedia Britannica includes in its 2007 Macropaedia almost 700 in–depth articles while the 2007 Micropaedia has some 65,000 articles [28].

How are government agencies responding to openness? Many are embracing it.

In Brazil, support for open source has been provided since 2003, with millions of dollars for infrastructure and education [29]. Workshops around the country are providing training for thousands of municipal and state administrators. Brazil’s IT policy was clearly stated by its Minister of Foreign Affairs at the recent Information Society World Summit in Geneva. I quote:

| “Brazil sees free software as emblematic of the Information Society and of a new culture of solidarity and sharing ... . The development of free software needs to be stimulated by different actors: governments, the private sector, and civil society.” [30] |

Other national governments supporting open source — in one way or other — include Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, and Venezuela, among others. Many governments are basing these decisions on the sheer cost of proprietary products, such as Microsoft Windows and Office [31]. In other cases, some governments see open source programs as more secure and reliable than comparable proprietary programs. These collective bureaucratic decisions add incredible momentum to open source.

The simplicity of openness

Why does openness work? Perhaps because of its simplicity.

Most open projects start along one of two paths.

The first path I call “Oh man, that really irritates me!” Richard Stallman initiated the Free Software Foundation — all because he wanted to stop his new Xerox printer from jamming in his MIT office [32]. He asked Xerox for the printer’s drivers — and Xerox said no, they were proprietary. Infuriated, Stallman re–examined the whole notion of software — and thought of a better way to make software available, so anyone would have the freedom to make changes to software — as they saw fit. Hence the “free” in the Free Software Foundation (http://www.fsf.org/) means the freedom to work with a program and contribute it to a commons for all to use.

Blake Ross, then a seventeen–year–old, began to work on a new Web browser — tired of spam and other security problems created in part by Internet Explorer. Working with openly accessible code for Netscape’s browser, Firefox appeared on the scene in November 2004 [33]. Thousands of volunteer programmers worked with Blake to create a better browser. Thanks to its security measures, Firefox has rapidly claimed more users, further eroding Internet Explorer’s dominance. Firefox worldwide has 30 percent of the Web browser market, capturing nearly 60 percent of the market in some countries such as Germany [34].

We might call the path followed by Stallman and Ross as the “way of the oyster.” A little irritation in an oyster is covered with calcium and protein, eventually producing a pearl [35]. We might think of many open projects as pearls in production, some already creating quite fashionable necklaces.

Another path is simply the sheer joy of creating something new and different. Linus Torvalds’ Linux was initially created out an effort to make a neat program. First Monday interviewed Linus in 1998 and he remarked [36]:

| “Linux was just something I had done, and making it available was mostly a ‘look at what I’ve done — isn’t this neat?’ kind of thing ... Making Linux freely available is the single best decision I’ve ever made.” |

On both paths, open projects attract a group of individuals that contribute to the longevity of a project — with ideas, comments, criticism, and support. These open communities — thanks to technology — are dynamic and active, ignoring the constraints of geography and time.

In turn, this social structure leads to the development of a commons. This commons becomes a well of new ideas, drawing in new participants, encouraging old hands to continue to develop ideas and dreams into reality.

ICOAST

What will the future bring?

I have something that might pass for an idea.

We need to prepare for the future of openness — for the future creators of openly accessible journals and magazines — for the new inventors of open source programs — for the new scholars and educators developing open courses. We need an actual place for these new ideas to percolate — besides the Internet — where formal and informal classes will cover a variety of topics — from new flavors of Web search engines, to Internet mechanics, to legal and policy issues.

I even have a name for this place, the International Center for Open Access Scholarship and Teaching. Makes for a perfect acronym, ICOAST, and I must thank my wife for both the name of the center and its acronym.

I’d like to see ICOAST be part of Dominican and the Graduate School of Library and Information Science. It would be a center for teaching and learning — not only for future librarians but for future policy–makers, teachers, and programmers, not only educating, but instilling the values of openness.

ICOAST really has its roots in some ideas of John Dewey. A colleague recently reminded me about Dewey and his very democratic ideas about creating knowledge. All knowledge, Dewey noted, is the result of observations, experiments, conversations, and refection. Anyone can participate in this process of creating knowledge — and we all do. It is this vast experience that leads us to new shores collectively and individually. To quote Dewey [37]:

| “Consider the development of the power of guiding ships across trackless wastes from the day when they hugged the shore. The record would be an account of a vast multitude of cooperative efforts, in which one individual uses the results provided for him by a countless number of other individuals ... so as to add to the common and public store. A survey of such facts brings home the actual social character of intelligence as it actually develops and makes its way.” |

We are all, in our own ways, engaged in this great effort. Openness is just the latest manifestation, using technology as a catalyst for observations, experiments, conversations, and refection.

I look forward to sailing with you to those distant intellectual shores. Thank you.

Notes

1. See Jasper Fforde’s Web site at http://www.jasperfforde.com/ as well as http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jasper_Fforde (accessed 15 July 2011).

2. Larry Sanger quoted in Wade Roush. “Larry Sanger’s Knowledge–Free–For–All: Can one balance anarchy and accuracy?” Technology Review 108, no. 1 (January 2005): 21.

3. “‘Free software’ is a matter of liberty, not price. To understand the concept, you should think of ‘free’ as in ‘free speech,’ not as in ‘free beer’.” From “The Free Software Definition.” GNU Operating System. http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.html (accessed 15 July 2011).

4. This “onion” model is full explained in Kevin Crowston and James Howison “The social structure of Free and Open Source software development.” First Monday 10, no. 2 (February 2005). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/1207/1127 (accessed 15 July 2011).

5. Alan Cox. “Cathedrals, Bazaars, and the Town Councils.” 1998. http://www.ibiblio.org/oswg/oswg-nightly/oswg/en_US.ISO_8859-1/articles/alan-cox/town-council/tcouncil.rtf (accessed 15 July 2011).

6. Eric S. Raymond. “The Cathedral and the Bazaar.” First Monday, 3, no. 3 (March 1998). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/578/499 (accessed 15 July 2011).

7. http://squirrelmail.org/ (accessed 15 July 2011) as well as http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SquirrelMail (accessed 15 July 2011).

8. Kevin Crowston and James Howison. “The social structure of Free and Open Source software development.” First Monday, 10, no. 2 (February 2005). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/1207/1127 (accessed 15 July 2011).

9. Chaoming Song, Shlomo Havlin and Hernán A. Makse. “Self–similarity of complex networks.” Nature, 433, no. 7024 (27 January 2005): 392–395.

10. Directory of Open Access Journals http://www.doaj.org/ (accessed 15 July 2011).

11. As of July 2011; see http://firstmonday.org (accessed 15 July 2011).

12. David Noble. “Digital diploma mills: The automation of higher education.” First Monday, 3, no. 1 (January 1998). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/569/490 (accessed 15 July 2011).

13. For more details, see the OpenCourseWare Consortium http://www.ocwconsortium.org/, as well as http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OpenCourseWare (accessed 15 July 2011).

14. “About SourceForge” http://sourceforge.net/about (accessed 15 July 2011).

15. Read First Monday’s interview with Linus Torvalds “FM Interview with Linus Torvalds: What motivates free software developers?” First Monday, 3, no. 3, http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/583/504 (accessed 15 July 2011).

16. “Tadeáš Hájek” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tadeas_Hajek (accessed 15 July 2011).

17. “Pietro Andrea Mattioli” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pietro_Andrea_Mattioli (accessed 15 July 2011).

18. Tullimonstrum was originally described in Eugene S. Richardson, Jr. “Wormlike fossil from the Pennsylvanian of Illinois.” Science 151, no. 3706 (1966): 75–76; noted in Ralph Gordon Johnson and Eugene S. Richardson, Jr. “A remarkable Pennsylvanian fauna from the Mazon Creek area, Illinois.” Journal of Geology 74, no. 5, Part 1 (1966): 626–631; and treated in detail in Ralph Gordon Johnson and Eugene S. Richardson, Jr. “The morphology and affinities of Tullimonstrum.” Fieldiana: Geology 12, no. 8 (1969): 119–149. See also “Tullimonstrum.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tullimonstrum (accessed 15 July 2011).

19. “State Symbol: Illinois State Fossil — Tully Monster (Tullimonstrum gregarium).” http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/symbols/fossil.html (accessed 15 July 2011).

20. “By the end of 2010, the Internet had a total of 255 million websites. ... Apache went from hosting 109 million websites in 2009, to almost 152 million by the end of 2010.” Hence Apache was used on 59.6% of worldwide Web servers. From “Apache web server hit a home run in 2010.” (4 January 2011). http://royal.pingdom.com/2011/01/04/apache-web-server-hit-a-home-run-in-2010/ (accessed 15 July 2011).

21. “Google platform.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_platform (accessed 15 July 2011).

22. “Linux adoption.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linux_adoption (accessed 15 July 2011).

23. “IBM is committed to Linux and Open Source.” http://www-03.ibm.com/linux/ (accessed 15 July 2011).

24. “Patents and Innovation.” http://www.ibm.com/ibm100/us/en/icons/patents/transform/ (accessed 15 July 2011); see also “Corporations Go Public With Eco–Friendly Patents.” http://www-03.ibm.com/press/us/en/pressrelease/23280.wss (accessed 15 July 2011).

25. “OpenSolaris.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OpenSolaris (accessed 15 July 2011); see also “Welcome to the OpenSolaris Community.” http://hub.opensolaris.org/bin/view/Main/ (accessed 15 July 2011).

26. “Quarterly earnings: IBM reports 2010 fourth–quarter and full–year results.” http://www.ibm.com/investor/4q10/press.phtml (accessed 15 July 2011).

27. “Wikipedia.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia (accessed 15 July 2011).

28. “Encyclopaedia Britannica.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Encyclopaedia_Britannica (accessed 15 July 2011).

29. “Brazil and Open Source.” http://www.charlesleadbeater.net/cms/xstandard/Brazil_Open_Source.pdf (accessed 15 July 2011); see also Steve Kingstone. “Brazil adopts open–source software.” BBC News (2 June 2005). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/4602325.stm (accessed 15 July 2011).

30. Ambassador Samuel Pinheiro Guimarães Neto, quoted in Alexandre Silva Pinheiro and Henrique Luiz Cukierman “Free software: Some Brazilian translations.” First Monday, 9, no. 11 (November 2004). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1189/1109 (accessed 15 July 2011).

31. Rishab Aiyer Ghosh “Licence fees and GDP per capita: The case for open source in developing countries.” First Monday, 8, no. 12 (December 2003). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/1103/1023 (accessed 15 July 2011).

32. Sam Williams “Chapter 1: For Want of a Printer.” In: Free as in Freedom: Richard Stallman’s Crusade for Free Software. (Sebastopol, Calif.: O’Reilly, 2002). http://oreilly.com/openbook/freedom/ch01.html (accessed 15 July 2011).

33. “Blake Ross.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blake_Ross (accessed 15 July 2011).

34. “Firefox.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mozilla_Firefox (accessed 15 July 2011).

35. Neil H. Landman, Paula M. Mikkelsen, Rüdiger Bieler, and Bennet Bronson. Pearls: A natural history. (New York: Abrams, 2001), 41–46; see also “Pearl.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pearl (accessed 15 July 2011).

36. “FM Interview with Linus Torvalds: What motivates free software developers?” First Monday, 3, no. 3 (March 1998). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/583/504 (accessed 15 July 2011).

37. Larry A. Hickman and Thomas M. Alexander (editors). The essential Dewey. Volume 1: Pragmatism, education, democracy. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 327.

About the author

Edward J. Valauskas was the second Follett Chair in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at Dominican University from 2004 to 2007. He is currently Lecturer in the School at Dominican. He is also Chief Editor and Founder of the peer–review, open access journal First Monday (http://firstmonday.org). Finally, Edward is Curator of Rare Books at the Lenhardt Library of the Chicago Botanic Garden.

E–mail: ejv [at] dom [dot] edu.