The Library is Dead: Long Live the Library

The Third Follett Lecture, Graduate School of Library and Information Science,

Dominican University, 22 February 2007

Edward J. Valauskas

Abstract

This paper analyzes the development of digital collections and libraries over the past decade, and their influence on the growth of libraries and their collections. In particular, it proposes that future libraries will be more connected than ever with their patrons, providing access to not only traditional local users but also patrons working under very special circumstances. Technology will indeed make it possible for libraries to specialize their collections to the needs of individual patrons in spite of differences of time and location.

Introduction

Good evening President Donna Carroll, President Christopher Traut of the Follett Corporation, Dean Roman, colleagues, and students.

It has been a distinct and special honor to have been the Follett Chair in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at Dominican University for the past three years. I am very grateful to the Follett Family and the Follett Corporation for enabling me to be part of Dominican University, to work with some of most remarkable students I have ever encountered in my career as well as with distinguished colleagues, my fellow faculty in the School. It is difficult to believe that three years have passed so quickly. As I end my term here at Dominican, I could go through a laundry list of my accomplishments as Follett Chair. It might entertain you and certainly would inflate my head no end. Certainly in the course of the past few months, I have thought about my experiences over the last three years. What has been my single outstanding contribution as Follett Chair? Well, it has to be my students. Every day for the past three years, each of my students has stunned me with their creativity, energy, wit, humor, and professionalism. My students have been a constant source of wonder and surprise.

I must admit that I have had my fair share of students in the past 36 months, in nearly a dozen different classes. These classes are formally listed in the School’s catalog as LIS 710 Descriptive bibliography, LIS 711 Early books and manuscripts, LIS 712 History of the printed book, LIS 717 Human records and society, LIS 742 Reference sources in the sciences, LIS 753 Internet fundamentals and design, LIS 755 Information policy, LIS 796 Special topics: Internet publishing, LIS 812 Seminar: Scholarly communication in the sciences, LIS 815 Seminar: Virtual worlds, plus independent study projects and practica. These classes have been for me a tonic, an elixir, a magic potion, stimulating my imagination and intellect in ways that I could have never predicted three years ago. I could spend the rest of the evening talking about my remarkable students — but instead I will brag about them with only a few stories.

I have also had a chance to teach elsewhere. Just a few weeks ago, I taught an enjoyable class on rare botanical books at the University of Chicago’s Graham School of General Studies. I also lectured at the Milton Hershey School in Hershey, Pennsylvania, as part of the festivities around the Plants in Print exhibit, an exhibit of rare books from the collection of the Library at the Chicago Botanic Garden. I am the curator of that exhibit which has toured to Washington, D.C. and the U.S. Botanic Garden. In a few weeks, Plants in Print: The Age of Botanical Discovery will be heading to Atlanta and the Atlanta History Center.

A group of my students some three years ago took on a formidable project, taking a print scholarly journal published by the School called World Libraries and converting it into an openly accessible Internet resource. I initially thought that project would take two years to set up; we essentially had a digital product in six months. Students in my Internet Publishing classes continue this effort by putting online each semester at least one issue from the past archive and one new issue. Some of my students from these classes have gone on to become editors and production assistants in another journal entitled First Monday. Other students from these classes are now creating digital content in libraries around the country.

I have had many delightful students in a class entitled Information Policy. In that class, we discuss current issues related to privacy, copyright, Internet access, and digital content, reading many legal documents and opinions. I usually bring to class one or two lawyers as guest lecturers over the course of each semester. These barristers are always impressed with the intensity and imagination of my students. Last Spring, one of my students in Information Policy came up with a remarkable idea. How had the definition of “library” changed in legislation in the United States since the events of September 11? She wrote a preliminary investigation into this topic last Spring, fleshed it out in an independent study with me last Summer, and I recommended her paper to several editors for publication. It will appear next month in the prestigious international journal Libri [1].

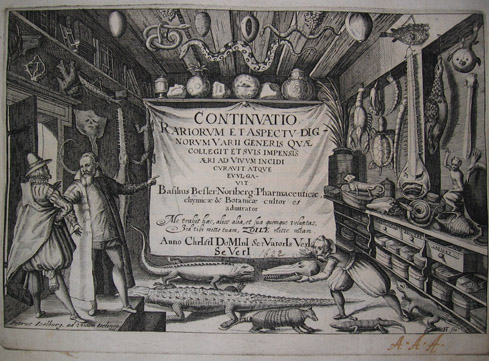

Finally I have to share with you my sheer glee over the many students who have worked with me in classes over the last three years, examining rare books, journals, and manuscripts in the collection of the Library at the Chicago Botanic Garden. These students have made many discoveries in these incredible volumes, the earliest published in 1483. One group of students took on the challenge of deciphering a very rare book by one Basilius Besler, a Nuremberg pharmacist who lived from 1561 to 1629. Basilius late in his life created one of the most important botanical books ever published entitled Hortus Eystettensis for the Prince Bishop of Eichstätt in southern Germany. As a result of this work, Besler became an advisor to the well–to–do on creating cabinets or amateur natural history collections in their homes. These collections eventually became the foundations of many great museums in Europe. In 1622, Besler published a little guide for the beginning collector (see Figure 1). It is a curious book with engraving after engraving of all sorts of stuffed animals, fossils, minerals, and seeds that should be in your natural history collection at home. But is that really what this book is about? Three of my students took on this puzzle and I think they have may have found an answer. The book is more than just a catalogue of what sorts of lizards and fish should decorate your walls. It is indeed a rejection of medieval notions of the natural world, a place where certain trees gave birth to fish and birds and rare shrubs produced sheep. The book rather is a call for logic and classification, a careful cataloging of nature to better understand relationships and origins. I have some editing to do on the manuscript and I hope to see it in print soon.

|

| Figure 1: The title–page from Basilius Besler’s (1561–1629) Continuatio rariorum et aspectu dignorum varii generis quae collegit et suis impensis aeri ad vivum incidi curavit atque evulgavit (Nuremberg, 1622). Note: Image courtesy of the Lenhardt Library at the Chicago Botanic Garden. |

I apologize to those students whose stories I have not shared this evening. But before I continue I would to thank you all for stimulating and challenging me for the past three years, making me think, laugh, and rejoice each and every day.

Many of my students have heard me talk about my library experiences in one way or another over the course of the past three years. Libraries have profoundly affected me throughout my entire life and especially as a child. Why do libraries have such an effect? What is so addictive about a good library and good librarians? Are those sorts of libraries and librarians becoming extinct?

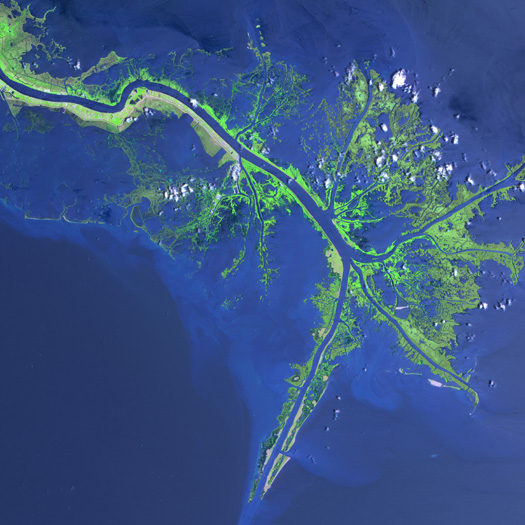

Let me tell you about one memorable library that I knew as an eleven–year–old. A little over 22,000 souls lived in Plaquemines Parish in 1960, the southernmost county in Louisiana, encompassing about 2,500 square miles (of which 35 percent happens to be land) [2]. Plaquemines is where the Mississippi River meets the Gulf of Mexico (see Figure 2). I would spend parts of my summers as a child in Plaquemines with the Ragas family in a little town at the south end of the parish called Buras. During World War II, my father served in North Africa, and then back in Louisiana as an MP, teamed up with Burt Ragas from Louisiana and a Shawnee Indian from Oklahoma by the name of Kim. They must have made quite a team. The Ragas family owned a gas station, a fishing boat, an orange grove, and a winery (to make orange wine no less) in Buras. I would spend my summers with my brother and sister collecting lizards in the orange grove, going to the levee to watch ships sail past up and down the Mississippi, go fishing with Burt in the bayous west of Buras out into the Gulf of Mexico, or explore the recently restored Civil War Fort Jackson. Those were pretty idyllic summers, a kind of Huck Finn existence in the semitropical heat of Plaquemines Parish.

|

| Figure 2: Mississippi River delta. Note: Image captured by NASA’s Terra satellite on May 24, 2001, at http://http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/. |

One summer across the street from Burt’s gas station construction started on a public library. I was ecstatic! By the way there was only one street in Buras, a two–lane highway labeled State Route 23 that took you north and west some sixty–three miles to New Orleans or south and east to a dead end fifteen miles away to Venice and Pilot Town. When the library opened I was especially thrilled because it was the only public air–conditioned building in Buras, a great escape on those July and August warm and humid afternoons.

|

| Figure 3: Buras Public Library under construction, November 28, 1961. Note: Image from LOUISiana Digital Library, at http://louisdl.louislibraries.org/. |

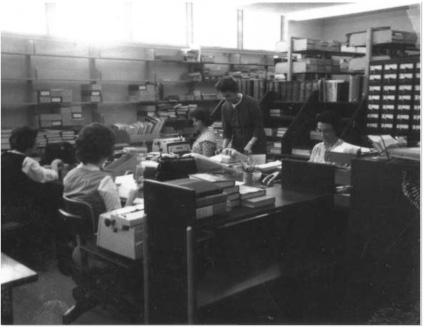

The staff of the Buras Public Library knew Plaquemines Parish well. Their local expertise provided plenty of information to a curious boy. Back then it was the centennial of the War of Northern Aggression (you might know that as the Civil War). I was very interested in Admiral David Farragut’s run past the Parish’s forts, Forts Jackson and Saint Phillip, in April 1862. They not only provided me with books and magazines and clippings, but pointed me to local residents, describing those events a century ago in the patois of the Parish, a mixture of Cajun, French, and English. Other times, I would collect shells along a beach west of Buras at the Gulf on an island appropriately called Shell Island. The staff would patiently explain the local names for the shells and point me to the right books to find their proper scientific titles. On other occasions, I was curious about the oranges in the Parish, their history and differences from oranges I knew back north. Again, I was given plenty of details on the distinct French origins of Buras’ orange groves from the eighteenth century. My questions about the geology of the Parish were answered with a publication from the state geological survey and pointers to the most knowledgeable locals working on oil rigs in the Gulf, or in sulphur mines just north in a little town entitled Port Sulphur.

|

| Figure 4: Buras Public Library staff, circa 1962. Note: Image from LOUISiana Digital Library, at http://louisdl.louislibraries.org/. |

What made this library special for me? It was the only place in the world for me that knew everything it seemed, about Plaquemines Parish. The library was the best place to go for local details. Isn’t that what libraries have always been about? Local knowledge and expertise, readily available with a smile and encouragement.

On Monday morning August 29, 2005 at 6 a.m. Hurricane Katrina first touched Louisiana at Buras. With a storm surge nearly thirty feet in height and winds in excess of 130 miles per hour, there was not much left of Buras. The library was simply an empty shell of a building. The orange groves were wiped out. But they are all slowly coming back. Orange groves and libraries recovered from Hurricanes Betsy and Camille in the 1960s; Katrina caused only a temporary hiatus in library service in south Plaquemines Parish.

|

|

| Figure 5: Buras Public Library children’s area before (top) and after (bottom) Katrina. Note: Images from Belle Chase Library, January 18, 2007. |

Buras and the Parish will not abandon their library because of Katrina, because all of the Parish libraries are integral local resources, institutions that the communities depend on.

Libraries have always been important local institutions. With technology, they are becoming even more integrated into local communities, both real and virtual. Charles Lyons, Business and Management Librarian at the University of Buffalo, N.Y., describes this local strength of libraries in a paper which appeared in First Monday [3]. Lyons sees libraries as the center of a variety of local resources, tools, and communities, not mere appendages. Lyons argues that libraries use technologies to work as producers and coordinators of local information, creating local search engines and local virtual communities to work with individuals in real communities, and to act as intermediaries to local governments and local media.

We are already seeing many libraries move in this direction, using technologies to essentially create a local brand for their local expertise. For example the New Haven Free Public Library, via its Web site (http://www.cityofnewhaven.com/library/), links patrons to city offices, zoning and municipal codes, and forms, plus provides calendars and classes on a variety of levels in several languages for its patrons. Plenty of community information is also available from the Champaign Public Library (http://www.champaign.org/), which uses the effective tag line “Our community connects at the library” [4].

Search engines are already being localized to meet the needs of everyone in communities. There certainly will be plenty of traffic; according to a recent study, 76 percent of adult U.S. Internet users perform some sort of local search online [5]. Creating a local search engine does not mean re–inventing Google. The London Ontario Public Library, for example, created MyCommunityInfo.ca (http://mycommunityinfo.ca/) that uses Google technology to focus on local Web sites.

|

| Figure 6: MyCommunityInfo.ca, London Ontario Public Library. |

Free applications like Rollyo (http://www.rollyo.com/) and SWiki (http://swiki.codeplex.com/) make it easy for libraries and even the most technophobic librarians to create customized search engines. Rollyo is a Yahoo!–powered search engine which allows users to register accounts and create search engines that only retrieve results from the Web sites and blogs they want to include in their search results. Users can also share their “rolled” engines with others. A Wiki is a collaborative hypertext environment; anybody can create or edit the pages; pages are linked by their names. They are fairly commonly used by the Georgia Institute of Technology’s College of Computing as collaborative group Web pages. It is also used in K–12 education and has been used successfully with fourth graders so that means we can we do it, too!

Local libraries provide access to the long tail of information, all of that stuff that Google never bothered to index and file away. My childhood experiences in Buras prove the value of local experts in the library, pointing to human resources scattered among the bayous and orange groves, shrimp boats and oil rigs. Local information is embedded in local communities. Libraries are creating new online resources, inventing new digital social networks to make local expertise even more accessible. Examples of these online local communities include BuffaloRising (http://www.buffalorising.com/) from Buffalo (New York) and SkokieTalk (http://www.skokienet.org/node/6384), sponsored by the Skokie Public Library, with another great tag line “News for the people, by the people.” These online communities are vibrant and important, especially to their participants and residents. A recent study from the USC Annenberg Digital Futures Project found that forty–three percent of Internet users who are members of online communities remark that they feel as strongly about their virtual communities as their real world communities [6]. Indeed, more libraries need to become a virtual social environment for their patrons, becoming a place to share information, socialize, and strengthen the local community.

Libraries are increasingly turning to new technologies to create new connections to their patrons. For example, pictureAnnArbor (http://www.aadl.org/gallery/pictureAnnArbor) collects digital images that reflect everyday life in the Ann Arbor (Michigan) area. The Wyoming Authors Wiki (http://wiki.wyomingauthors.org/) provides a connection to Wyoming authors and their books. The Dowling College Library provides podcasts about local Long Island history (http://www.dowling.edu/wikis/pmwiki.php/LISSHistory/LISSHistory)_ as well as monthly conversations about the community, including readings and interviews. In conjunction with the New York Law School and Second Life (http://nyls.blogs.com/demoisland/), Queens is designing a new park near LaGuardia Airport, virtually involving members of the community in the design as avatars testing different arrangements of trees, fountains, swing sets, walks, and walls. Indeed libraries can and should be the interface for the public to understand local government, working with officials in designing new and improving traditional services. Cascade Link (http://www.cascadelink.com/), for example, in Portland, Oregon provides access to a rich variety of local resources.

Yet more libraries need to take advantage of digital tools like TerraFly (http://www.terrafly.com/) and neighboroo (http://mashupawards.com/neighboroo/), and combine them with local government information into really creative resources. With TerraFly, you simply enter an address and retrieve aerial images so you can create your own digital atlases. Neighboroo provides you with an easy way to learn about neighborhoods, pulling information from a variety of official and digital sources.

Libraries indeed need to pull together different kinds of niche digital resources like TurnHere (http://www.turnhere.com/), Yelp (http://www.yelp.com), and Upcoming (http://upcoming.yahoo.com/) in innovative ways to reinforce the idea that libraries indeed are the center of local resources of every color and stripe. TurnHere provides a rich variety of Internet video from over 2,000 filmmakers in over fifty countries. Yelp gives you access to reviews of restaurants, cultural events, services, and organizations, written by what Yelp calls “real people.” Yelp merges social networking with local reviews. Upcoming is a social calendar Web site pulling together a variety of contributions by individuals and groups.

Are libraries as we now know them dead? Not dead, but undergoing an enormous transformation. The really successful libraries of this century will be those that become organizations at the center of it all, organizations that you can’t imagine their absence, organizations that really start your day. Should we call these places “libraries”? There have been other names that have been bandied about, like Vannevar Bush’s Memex, Ted Nelson’s Xanadu, and Hollywood’s Matrix. But all those fantasies are really quite simple–minded compared to the library that is just around the corner, created in one way or another by all of us. I’ll describe this new library shortly, but first, what about librarians? Are they dead? If anything, librarians are even more important, a more integral part of modern society and digital life, in my view. Indeed, I would argue that not only are libraries becoming the center of local and online communities, but librarians are also becoming key players. Imagine librarians as local avatars, intelligent agents, digital concierges for their patrons. Think of librarians as intermediaries helping users to create their own, or providing them with, daily reports on the news and events.

These librarians will be a little different from librarians of the past. In my previous Follett Lectures, I have emphasized the importance of librarians and libraries as content creators and developers and as explorers, guides, and agents in virtual worlds. In this Lecture, I tie together those threads by pointing out the need for librarians to be simply fearless about new technologies. Fearless also means being ready to fail, because not all new technologies will last. Our institutions have to be ready to accept that failure, too. But if we encourage a kind of fearlessness, I have high hopes for future generations of librarians and their libraries.

We will need to think about how we educate librarians for the future, emphasizing this fearlessness not only towards technology, but also in our attitudes towards patrons and clients (both real and virtual), in our tasks as information synthesizers, collectors, publishers.

Library schools will have to think about the ways in which they train future leaders in the profession. I see classes really concentrating in three areas: first, in encouraging expertise with current Internet and computer technologies in order to be creative with new and very different future technologies; second, in developing real familiarity with legal and governmental landscapes in order to be effective agents for policy change in the future; and, third, in perfecting human and virtual interactive skills, understanding how to work well with patrons no matter where they are encountered.

What will my Buras Public Library look like in the near future? First of all, I will be able to interact with the staff virtually from anywhere, say from my office here at the University, or on one of my fossil collecting adventures in Germany. The librarians in Buras will provide me daily feeds, reports — a sort of customized newspaper — with details on the weather; traffic on the Mississippi; status of the orange crops, shrimp, crayfish, oyster, and red snapper sales; any status of wetlands restoration in the marshes just west of the Library. Right now, each week I look forward to the Plaquemines Gazette (http://plaqueminesgazette.com/), the only newspaper in the Parish, arriving in my mailbox. In a sense, I will have another kind of newspaper appearing in my e–mail, customized to my own interests.

Where I see this virtual library really developing is in the use of recommender systems. Imagine Netflix working on a local scale, in a library, with librarians connecting individuals of similar interests. Let’s call it NetBuras. Thanks to this system, I am connected to pilots at the Southwest Pass, sedimentologists working on coastal restoration along Shell Island and Bastian Bay, the cook at the Little Fish Restaurant in Buras, the editor of the Plaquemines Gazette, and the captain of the Poine à la Hache ferry across the River. The librarians at Buras know that one of my most prized books is entitled the Art of Creole Cookery by William Kaufman and Sister Mary Ursula Cooper. Sister Mary Ursula was head of the home economics department at St. Mary’s Dominican College in New Orleans when this cookbook appeared in 1962. So thanks to their knowledge of my interest in gumbo recipes, there will be a little serendipity in this recommender system, with occasional tips on perfecting my roux. Podcasts will provide me with a audio encouragement in the kitchen!

In Second Life, we could create a Virtual Plaquemines Parish Library, reborn and definitely safe from the next hurricane. It will be the place for anyone to connect to the Parish government, Corps of Engineers, state bureaucracies such as the Coastal Protection and Restoration Agency, and federal agencies like FEMA’s Public Assistance Program. Online documentation will be available, plus librarians as avatars to help you navigate queues, in a way parallel to the services already provided by the librarians in the Parish to their patrons.

In a virtual world, these services are available anywhere and at anytime. In hurricane season, access to basic information about the state of the Parish and specifically your home, family, and friends is crucial. This virtual place provides a trusted repository, a familiar place in a morass of digital information. Think of it as the single place you would go to understand exactly the reality of the Parish, especially in the aftermath of a disaster.

At one level, then, the library is a publisher and consolidator of existing information. At another level, it acts as referral and recommender systems linking together like–minded people and organizations. At still another individual level, librarians act as intermediaries to bureaucracies, ready to take you to the head of the line.

Libraries and librarians will have multiple realities, in one fashion in buildings and offices and desks and stacks. But they will also exist online in virtual spaces, created collaboratively with their patrons and clients. Think of these virtual libraries as extensions, extensions that you utilize to transcend the limits of space and time. Libraries will ultimately transform into transcendental institutions. Transcendental to the point of being, dare I say it, cool. Libraries and librarians will become distinctly cool, naturally in the classic sense of cool. Understand that cool is not associated with a thing — but with community and imagination. You cannot declare yourself cool, you just are. Libraries truly will be cool and, paradox of all paradoxes, librarians will become the ultimate symbols of a sort of counter–culture valence of cool in an information–glutted world. Imagine that.

Thank you.

Notes

1. Tracy Hartman. “The changing definition of U.S. libraries.” Libri, 57, no. 1, 2–8 (2007): http://www.librijournal.org/2007-1toc.html (accessed 12 December 2011).

2. “Plaquemines Parish government,” http://www.plaqueminesparish.com/ (accessed 12 December 2011).

3. Charles Lyons, 2007. “The library: A distinct local voice?” First Monday, 12, no. 3 (March 2007): http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1629/1544, last accessed 12 December 2011.

4. “Our Mission & Five–Year Plan.” Champaign Public Library. http://http://www.champaign.org/about_us/mission_plan (accessed 12 December 2011).

5. “Search Engines Solidify Position as Source of Local Business Info.” (June 27, 2011). http://http://www.emarketer.com/ (accessed 12 December 2011).

6. “Online World As Important to Internet Users as Real World?” http://www.digitalcenter.org (accessed 12 December 2011).

About the author

Edward J. Valauskas was the second Follett Chair in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at Dominican University from 2004 to 2007. He is currently Lecturer in the School at Dominican. He is also Chief Editor and Founder of the peer–review, open access journal First Monday (http://firstmonday.org). Finally, Edward is Curator of Rare Books at the Lenhardt Library of the Chicago Botanic Garden.

E–mail: ejv [at] dom [dot] edu.